By Jefferson Siegel

Weeks of mounting tension at The New School erupted last Wednesday as a group of students took over the Greenwich Village university’s largest cafeteria and barricaded themselves inside, while calling for the resignation of the school’s president, Bob Kerrey, among a litany of other demands.

Last Wednesday evening several dozen students occupied the ground-floor cafeteria in The New School graduate faculty building on Fifth Ave. to protest the policies of school president Kerrey. By the time the occupation ended peacefully early Friday morning, the students had won concessions from Kerrey on a number of issues.

Students and faculty members had expressed dissatisfaction with Kerrey, a former governor and U.S. senator from Nebraska, as far back as his appointment as school president in 2001. His invitation for his friend Senator John McCain to deliver the keynote address at the school’s 2006 commencement resulted in protests, a tumultuous graduation ceremony and a “die-in.”

In recent weeks, tensions again boiled over when the school’s provost, the fifth in seven years, resigned and Kerrey assumed the position on a temporary basis. Students had also protested their lack of a voice in decision making and a lack of resources.

At a meeting of the school’s Faculty Senate a week before the cafeteria occupation, tenured faculty met with Kerrey to address several of these issues. Shortly after, a majority of senior faculty members approved a no-confidence measure against Kerrey by a vote of 269 to 18.

On Sun., Dec. 14, the school’s Union for Politics posted an online petition and a Facebook page. Students signed on to express displeasure with the school becoming, in their view, primarily a profit-making enterprise, and to call for more transparency in the administration. As of this past weekend, 530 had signed the petition.

A meeting that Sunday night centered around the need to create an autonomous space for students on the rather physically disconnected campus.

“No common space meant no shared culture,” explained Fatuma Emmad, a graduate student in politics at the school. Emmad was one of the core negotiators during the cafeteria occupation.

The day before the occupation, 40 students tried to enter a faculty meeting in the auditorium of the school’s Eugene Lang Building, at 65 W. 11th St., to voice their concerns but were blocked by school security guards. After a brief scuffle, eight students symbolically wearing tape over their mouths managed to get inside.

Late Wednesday afternoon an e-mail called students to meet in the school’s cafeteria inside the Albert List Academic Center building, at 65 Fifth Ave., between 14th and 13th Sts. By 8 p.m. that night dozens had pushed tables and chairs to the side of the dining/study area and hung a banner on a wall that declared the space the “New School in Exile.”

(The name was an apparent allusion to The University in Exile, founded in 1933 as a graduate division of the New School for Social Research as a refuge for academics fired from universities in fascist-ruled European countries.)

Despite repeated attempts by school security to empty the List building, students moved freely between rooms to use bathrooms on other floors. By the building’s 11 p.m. closing time, the students were firmly entrenched in the ground-floor space.

The students drew up a list of demands, chief among them the resignation of Kerrey, as well as the school’s vice president, James Murtha, and Robert Millard, the treasurer of the board of trustees.

Other demands included a request for transparency of investments, creation of a socially responsible investment committee and use of the List building as an autonomous student space until a permanent space could be created.

Thursday saw tensions rise between students and school security as the standoff continued. Standard procedure at the school had been to allow students from a local inter-university consortium of other schools to use the building’s facilities. However, school security was now allowing only New School students to enter 65 Fifth Ave.

Late in the morning students opened a side door on E. 13th St. to allow nonstudents to enter. A confrontation with security ensued as guards tried to prevent outsiders from joining the occupation.

“The side door opened and a bunch of individuals were led through by New School students,” said Maria, a Hunter College political science student who declined to give her last name. “The next thing I knew, a security guard lifted me and threw me to the ground.”

Maria said she then saw a guard grab a student by the neck and push him against a wall. In the narrow hallway, students picked up chairs to build a barricade while security guards used dumpsters to block the outside door so that no one could enter.

Claire, a junior at New York University who also declined to give her last name, noted the security guards “were really aggressive. I got shoved to the ground,” she said.

During the hallway fracas, one person, who was not a New School student, was arrested and taken to the Sixth Police Precinct.

In an e-mail to The Villager, Deborah Kirschner, a New School spokesperson, said police were called, “in an attempt to mitigate the inherent safety hazard represented by the barricades.”

Kirschner added, “In this post-Virginia Tech world, we must have zero tolerance for security risks.” The reference was to the April 2007 massacre at Virginia Polytechnic Institute, where a student shot and killed 32 students.

Later in the day, Kerrey issued a statement, saying, in part, “We do not have the numbers or training [of security personnel] necessary to deal with a situation like this without help. Accordingly I have called Police Commissioner Ray Kelly for assistance.”

Over the next several hours, as police took up positions at the front and side doors, students involved in the sit-in emerged to explain their motivations.

“We feel we’ve been silenced by the administration,” said Chelsea Ebin, a New School graduate student studying politics. “We want recognition of what’s happened to the university. Bob Kerrey and James Murtha have engendered an ethic that’s contrary to the history of the school.”

As the day progressed, students and protesters waited on the sidewalk outside. By late afternoon, groups from other schools started arriving, many shaking plastic bottles filled with coins while chanting, “War criminal Kerrey, get out now.” They were referring to an incident during the Vietnam War in 1969, when a Navy SEAL team led by Kerrey killed 21 civilians — women, young children and an elderly man — while on a mission in Thanh Phong.

At 7:40 p.m. the building was locked down and no one was allowed to enter or leave. Police and school security stood waiting in the main lobby. Minutes later, three students arrived carrying pizzas and other supplies. At first denied entry, they were eventually allowed to send the food inside.

As night fell and the crowd outside grew larger and noisier, Jean Rohe stood near the entrance, quietly strumming a mandolin. Rohe, a 2006 New School graduate, spoke at the school’s commencement that year before John McCain gave his speech.

At that 2006 ceremony, rather than deliver a boilerplate homage to hopes and aspirations, Rohe instead galvanized the audience with a measured, critical assessment of McCain and the Iraq War.

Thousands in the audience that day, many of whom would later stand and turn their backs on McCain in defiance, listened as Rohe declared, “The senator does not reflect the ideals upon which this university was founded.”

As Kerrey and McCain sat stone-faced, Rohe concluded, “These words I speak do not reflect the words of a young, strong-headed woman but come out of a tradition of progressiveness of The New School.”

On Thursday night, Rohe, who has just released her first music CD, “Lead Me Home,” again spoke softly but with no less determination. “Kerrey’s way of running the school — the top-down corporate structure — leaves very little room for students and faculty to guide the learning community here,” she lamented.

As Rohe spoke, a meeting of the University Student Senate was scheduled in another building. However, at the last minute an e-mail from the school administration announced the meeting was cancelled and that all school buildings were now closed. Several students said a second attempted sit-in at the Lang Building by 20 students was curtailed by school security, prompting the schoolwide shutdown.

By 10 p.m. the crowd on Fifth Ave. had swelled to several hundred. Students, activists and anarchists held a speak-out on issues of education, gay marriage, homelessness and the student body’s struggle for rights.

Inside the building, four student negotiators, including Emmad and Ebin, had started intense talks with psychology professor William Hirst and Linda Reimer, New School vice president of student affairs. The negotiations were taking place in the reading room next to the occupied cafeteria.

At 10:30 p.m. members of the Univer-sity Student Senate emerged. Peter Ian-Cummings, president of the senate, read a revised list of demands that were under discussion.

As the List building’s 11 p.m. closing time approached, many on the street expressed concern that a face-off between students and police was imminent.

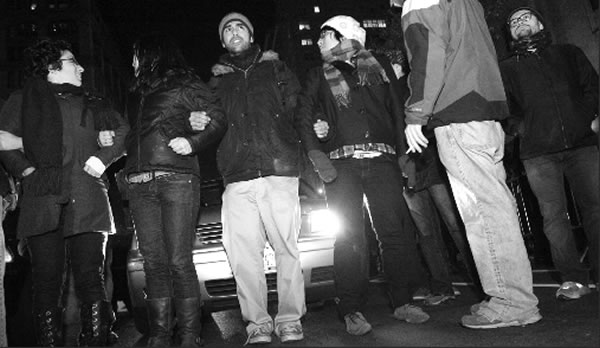

By now, the sidewalk in front of the building was packed with chanting students and activists. Police initiated crowd-control measures by setting up two rows of metal barricades: one stretching out into a lane of traffic to surround the students and a second, narrower passageway further out to allow pedestrians to pass.

Many in the crowd viewed this development as restrictive and swarmed onto the street on Fifth Ave. Some wore masks and bandanas over their faces. Several people locked arms to block traffic while others overturned newspaper boxes and garbage cans into the street. After several minutes, the crowd marched up Fifth Ave. and onto 14th St., stopping to gather by an unmarked side door of the school building. Someone on the inside opened the door and several dozen people rushed inside. On the third floor, someone broke a window, the shattered glass falling onto those entering the building.

Once the door closed, the rest of the crowd returned to the front as police reinforcements arrived. A line of police took up positions along the metal barricades on Fifth Ave., white plastic handcuffs hanging from their belts, but they took no other action.

At 11:40 p.m. Kerrey suddenly exited the building surrounded by a phalanx of school security. He was followed down Fifth Ave. by two-dozen people, many screaming, “War criminal!” and “Resign!” As they reached the corner of 11th St., Kerrey and the guards broke into a run until reaching the front of his brownstone. Students remained on the street screaming, “Murderer!” and “Baby killer!”

At 12:30 a.m. Friday morning, one of the student occupiers sent word that access to the bathrooms had been cut off and the students had now barricaded themselves inside the cafeteria.

Sean Brosler, a student working toward his master’s degree in historical studies at the New School, had left the building with 10 others when police gave the occupiers one last chance to leave. He now stood in the cold night air and described the democratic process taking place inside.

“There’s a core group of about 10 people who tend to be the leaders of discussions,” Brosler said, adding that many of the students in the cafeteria were also working on their end-of-semester finals papers on laptop computers.

When an issue arose, everyone would gather in a circle around a single person, a facilitator, he said; each new issue had a different facilitator.

“They’ll do an up/down vote. People will act organically,” Brosler said of the system intended to exclude egos and achieve results.

Brosler said discussions centered around several core principles that were “unimpeachable,” including not talking directly with Kerrey in order not to legitimatize him, since one demand called for his resignation. Brosler said Kerrey — who had been sitting near the cafeteria while negotiations were underway — became visibly angered and left the building when students demanded preservation of 65 Fifth Ave. The three-story building is slated to be demolished this winter, eventually to be replaced with a 300-foot-tall, glass-sheathed structure. The building has been mostly emptied, with its uses having been relocated to temporary swing spaces.

Around 2 a.m. Friday, Kerrey had returned to the building. Someone on a phone with the occupiers reported that the school would agree to a total amnesty for all involved in the occupation. Energized by the report, students on the sidewalk chanted without letup for the better part of the next hour.

At 3:30 a.m. someone reported that the last demand — that the occupiers be allowed to exit through the front door — was a sticking point in finalizing the deal.

Finally at 3:40 a.m. the occupiers poured out a side door on 13th St. and were greeted with hugs and cheers. Many lit up cigarettes for their first smoke in several days.

They had refrained from smoking while inside 65 Fifth Ave. out of respect for their fellow nonsmoking protesters and — since smoking isn’t allowed in the building — out of fear of inflaming already-high tensions with security.

As several hundred people stood on 13th St. listening, student negotiator Emmad read the list of demands agreed to and signed by Kerrey.

The final list did not include either Kerrey’s or Murtha’s resignation. It did grant total amnesty to all involved in the occupation and included dropping charges against the student arrested in the hallway on Thursday.

Kerrey also agreed to allow students the use of the Fifth Ave. building, “until a suitable replacement is secured and instituted, which would include the reinstallment of suitable library and study space.” The school president also agreed to provide new library space in The New School’s Arnold Hall and 7,000 square feet of quiet study space in the school’s Sheila Jackson Galleries by the end of the spring semester.

The six-point document also granted student participation in establishing a committee for socially responsible investing; gave the University Student Senate “the ability to communicate with the student body freely” — something they said they had previously not been allowed — and granted access for a student senate representative to attend meetings of the school’s board of trustees.

“We weren’t being radical, we were being reasonable,” Emmad explained. “We were simply trying to defend our school.”

As 4 a.m. approached, the ebullient crowd walked to Union Square. After two nights and a day inside the cafeteria, one participant, riffing on a chant from earlier in the day, said, “This is what democracy smells like.” Then someone turned on a boom box and students began dancing.

After a peaceful climax to 32 hours of occupation, it seemed like the dawn of the 1960s Version 2.0.