BY TEQUILA MINSKY | The March weather was brisk, but with sunny skies the day mostly cooperated with the desire of participants to soak in the rare women who merited statuary recognition in New York.

“I’m disgusted that every public dedication for bridges, roads, airports are named for men,” Vilma Nelson said of her reasons for joining LuLu LoLo and the Municipal Art Society on the late winter excursion.

The day began where West 122nd Street forms a triangular junction with St. Nicholas Avenue and Frederick Douglass Boulevard, the site of one of the city’s newest and least familiar statues — honoring Harriet Tubman (1822-1913).

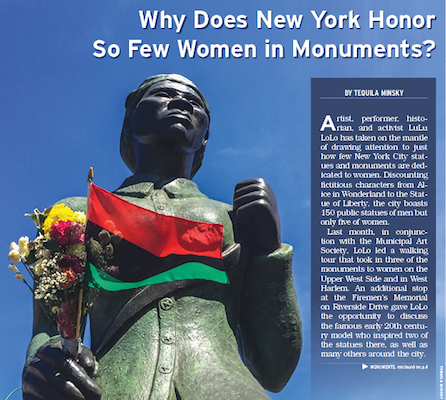

Sculptor Alison Saar, daughter of famed African-American artist Betye Saar, created a powerful monument to Tubman, who was born a slave in Maryland and escaped via the Underground Railroad in 1849. The statue depicts Tubman not as the “conductor of the Underground Railroad but as the train itself… the roots of slavery pulled up in her wake.”

Titled “Swing Low,” the statue was championed by former Manhattan Borough President C. Virginia Fields and dedicated in 2008. The junction is now known as Harriet Tubman Triangle, and a New York Department of Parks and Recreation information sign offers background information on the iconic abolitionist and on the memorial’s development.

Over a 10-year period and at great peril to herself, Tubman made numerous trips returning to Maryland to guide scores of family and friends to freedom.

The fact that the statue faces south stirred some controversy when it was completed, given Tubman’s commitment to lead slaves north to freedom. But from Saar’s perspective, “What is most impressive to me are her trips south, where she risked her own freedom.”

The skirt of the larger-than-life bronze figure has bas-relief images of “anonymous Underground Railroad passengers,” some inspired by West African “passport masks” that were worn in traditional performances there. The granite base has panels that alternate between events in Tubman’s life and historical quilting patterns.

From Harriet Tubman Triangle, the group continued to the Firemen’s Memorial at Riverside Drive and 100th Street. The memorial, dedicated in 1913, includes allegorical sculptures on the north and south side entitled “Duty” and “Sacrifice” attributed to Italian-born American sculptor Attilio Piccirilli.

Celebrated model Audrey Munson is said to have posed for these sculptures and also served as the inspiration for more than 15 other statues in New York City, including the figure on top of the Manhattan Municipal Building titled “Civic Fame,” also dedicated in 1913. In the immediate vicinity of the Firemen’s Memorial, Munson also modeled for the Isidor and Ida Straus Memorial, dedicated in 1915 at Broadway and 106th Street. Isidor was a co-founder of Macy’s and the Strauses died on the Titanic.

LoLo peppered her history lessons with tidbits of art gossip. For example, regarding the statue of “Pomona/ Abundance” at the Pulitzer Fountain by the Plaza Hotel, she explained that Cornelius Vanderbilt III’s wife Grace insisted on moving her bedroom in their Fifth Avenue mansion because she didn’t care to look out on the statue’s bare buttocks. Munson, LoLo said, was for years thought to be the model for Pomona, but now it’s attributed to Doris Doscher.

From the Firemen’s Memorial, a brief walk to Riverside Drive and 94th Street took the group to the Joan of Arc (1412-1431) created by sculptor Anna Hyatt Huntington and dedicated in 1915.

The sculpture was based on a model Huntington had submitted to the Paris Salon, where she received recognition despite the jury’s initial skepticism about such an accomplished work being a woman’s creation.

In Huntington’s vision, Joan raises her sword in strength to the heavens. Both Joan of Arc and Harriet Tubman, LoLo said, had dreams that informed the missions they would take on in life.

LoLo’s group next hopped a bus traveling down Riverside Drive to 72nd Street to see the monument honoring humanitarian and First Lady Anna Eleanor Roosevelt (1884-1962).

The inspiration for the memorial, LoLo explained, came from Herbert Zohn, a retired art dealer, when he was walking in March 1986 along Riverside Park near 72nd Street, not far from his home. At that time, the park there was shabby and Zohn thought it was a wonderful idea to have a statue of Roosevelt, whom he had long admired.

Zohn organized a board of local notables — Jackie Onassis, Helen Hayes, Katherine Hepburn, Senator Daniel Moynihan, Kitty Carlisle Hart, Harry Belafonte, and Mayor David Dinkins — to steer the planning. Through a national competition, a group of art historians and a Roosevelt family member selected sculptor Penelope Jencks.

Jencks modeled Roosevelt’s upper body after the first lady’s great granddaughter, Phoebe Roosevelt. According to LoLo, when Jencks was wrestling with doubts about the statue’s anatomy, she had a dream where Roosevelt was smiling and it erased her concerns.

Still, her work took four years instead of the expected 18 months to complete, and plans for the dedication were repeatedly postponed due to the sculptor’s exacting nature. The entire project took 10 years.

Ultimately, the state paid for removing an unused entrance to the Henry Hudson Parkway — ironically, a major New Deal public work — the city did landscaping and other improvements, and more than 2,000 donors gave money for the monument, which had a total cost of $1.3 million.

First Lady Hillary Rodham Clinton joined Jencks at the dedication in 1996.

During the walk, LoLo pointed to particularly stark statistics about the gender imbalance among statues in Central Park — 22 men and zero women. She mentioned the current campaign underway to erect statues of suffragettes Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony there.

“I want get more involved in advocating for public statues that recognize women and their achievements,” Vilma Nelson said as she was walking from one monument to another. A veteran of a number of other Municipal Society tours, Nelson was clearly inspired by the potential for increasing the roster of women who are honored in New York’s public monuments.