Yet we are free who live in Washington Square,

We dare to think as Uptown wouldn’t dare,

Blazing our nights with arguments uproarious,

What care we for a dull old world censorious,

When each is sure he’ll fashion something glorious?

From “The Day in Bohemia

or Life Among the Artists,”

— John Reed

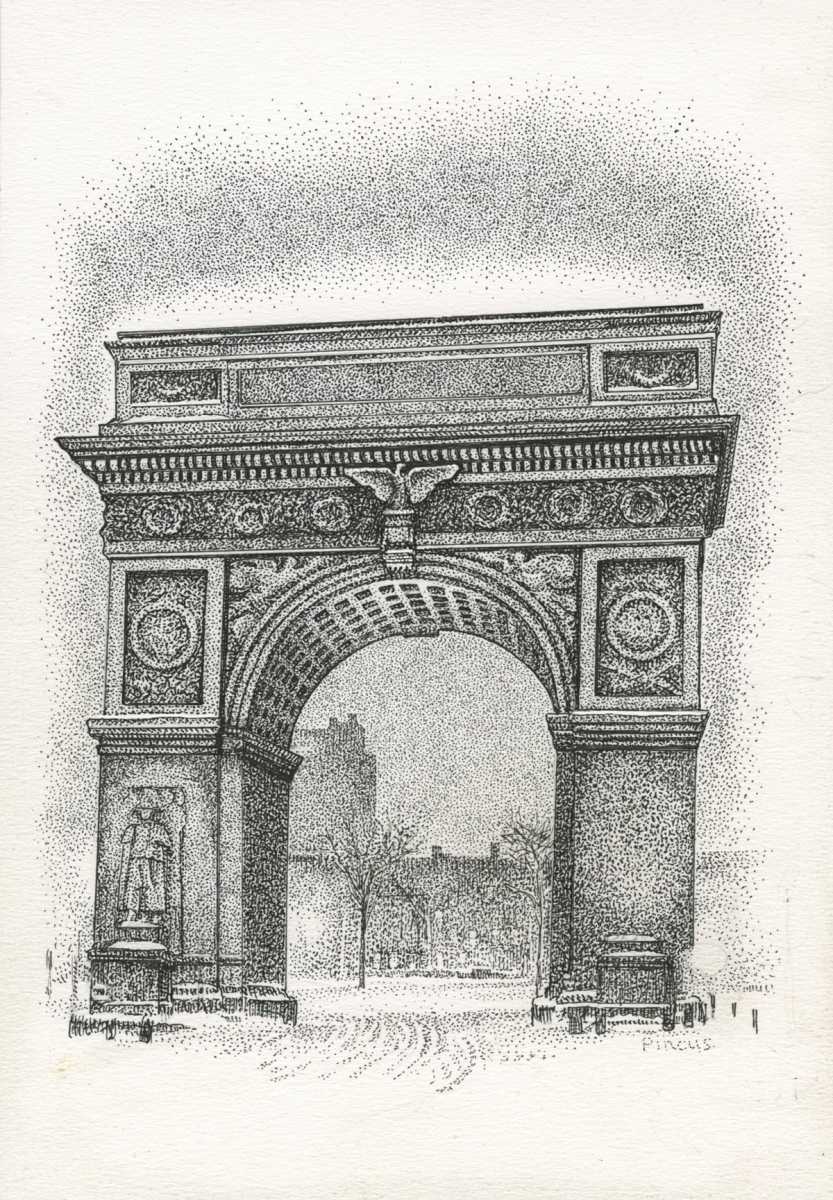

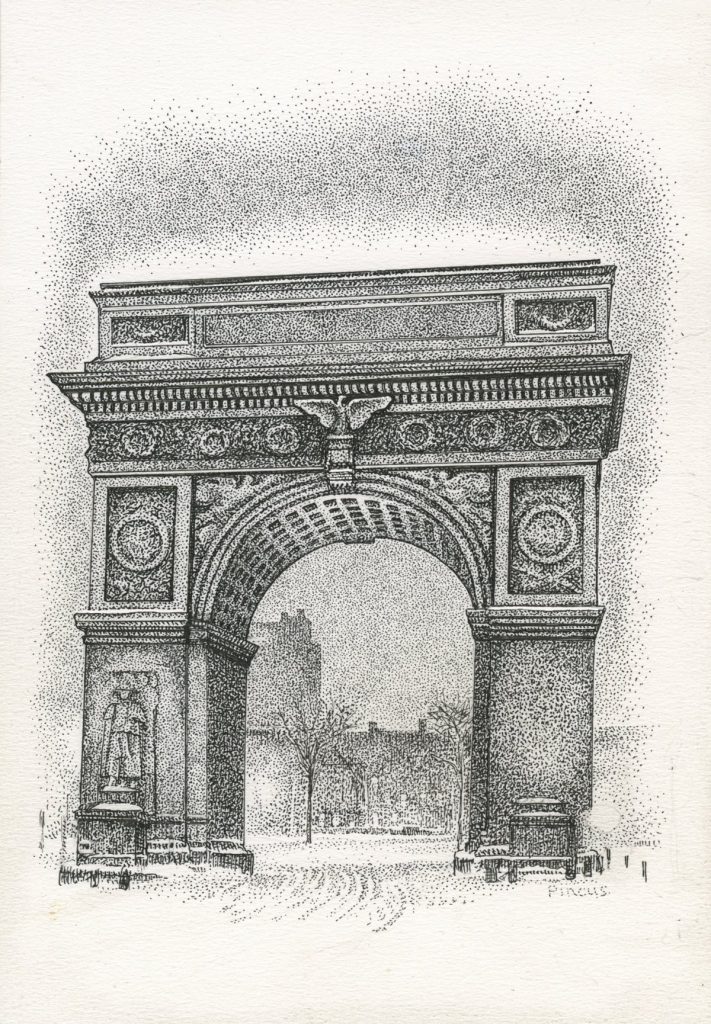

By Harry Pincus

Many years ago, I was strolling down Bleecker St., attempting to clear my head for an all-night illustration deadline. It was too late for street traffic, yet I suddenly happened upon a commotion of lights trained upon 45 Grove St., a memorable old edifice then fronted by two ancient and denuded lampposts. Now, as if in a vision, the empty posts were topped with illuminated globes, and a beautiful woman in an early-20th-century gown was descending the building’s ancient stairs.

It was Diane Keaton, as Louise Bryant, Jack Reed’s wife in “Reds,” Warren Beatty’s epic story of the revolutionary war correspondent for The Masses, and his Greenwich Village cohorts.

Beatty himself watched Keaton as she was leaving what was supposed to be Eugene O’Neill’s house and simply walking down the street. Dressed improbably in a black overcoat and informed by a video monitor, the great star-director objected to something in each take, and insisted that Keaton repeat the simple act of closing the front door and walking down the stairs, over and over again.

Finally, the front door of 45 Grove flew open, and an old woman in her housecoat, holding two bags full of garbage, stood stage center, glaring at the midnight assemblage. As she purposefully descended the stairs, the old lady managed to hurl every imaginable epithet, every filthy word one might ever have heard at the Hollywood director and his crew. As soon as she had loudly deposited her load, ascended the stairs and disappeared beyond the front doors, Beatty jubilantly exclaimed, “CUT! PRINT!”

Although that old building on Grove St. wasn’t actually O’Neill’s lair, it is said to have provided a meeting site for John Wilkes Booth and his conspirators. “Reds” did a great service in shining a light on the incredible group of artists, writers, poets and revolutionaries who walked these streets a century ago, who saw fun and art in rebellion, setting a template for the Greenwich Village that lives on today. They included the likes of Emma Goldman, Bill Hayward, Eugene O’Neill, John Sloan, Marcel Duchamp, Mabel Dodge Luhan, Max Eastman and a moody blonde violinist named Gertrude Drick, who took painting classes with Sloan. Dick handed out cards that simply said, “Woe.”

“Woe is me,” she would explain.

Ellis Jones, editor of a humor magazine called Life, claimed that the Village of 1916 was becoming stale with poseurs and tourists, and that the rents were too high. He tried to organize a Revolution in Central Park, but it was misplaced, and attended by more police than radicals.

Aside from the unspeakable labor conditions, poverty, bigotry and sexism inherent at the time, Europe was tragically engaged in the bloodbath of senseless war. Its siren call had to be opposed by the artists and writers who lived in the Village and worked for The Masses.

This was serious business for Reed, who, along with Publisher Eastman, cartoonist Art Young and several others, was brought up on federal charges under the Espionage Act, for conspiracy to obstruct military enlistment.

Henry J. Glintenkamp was cited for drawing a skeleton examining a healthy young conscript beside a pile of caskets. The title was “Fit for Service.”

Art Young had to defend his cartoon “Having Their Fling,” in which a capitalist, an editor, a politician and a minister are depicted in a dance of orgiastic abandon as Satan conducts an orchestra of war from a bandstand. Young also drew a military bureaucrat examining an enormous, headless brute, with the caption “Army Examiner: ‘At Last, A Perfect Soldier!’”

Young napped through most of his trial. When the judge insisted upon awakening the defendant, the artist took to pad and pencil and produced a self-portrait, asleep, called “Art Young on Trial for His Life.”

Sloan worked with Reed on The Masses, and painted the Village as he really saw it. Young called it the “ashcan style” and the expression came to encompass an entire school of social-realist painters.

Yet, no social realist was Duchamp, who scandalized the 1913 Armory show, where he met Sloan. Duchamp had rejected “retinal” art, and said he wanted to put art back into the mind.

All of this confluence, this mixing of genius, energy and resistance, somehow came to a head on the evening of Jan. 23, 1917. Yes, 100 years ago, almost to the day.

On that frigid night, Gertrude Drick, Marcel Duchamp, John Sloan and several actors from Eugene O’Neill’s nearby Provincetown Playhouse — Betty Turner, Russell Mann and Charles Ellis — managed to elude a patrolman and slip into the side door of the Washington Square Arch. The conspirators mounted the 110 spiral stairs, precisely constructed of ceramic tile by Rafael Guastavino, and emerged at the top of the arch with a supply of wine, cap pistols, balloons, Chinese lanterns and sandwiches.

It wasn’t long before the warmth of the wine had worked its wonders, and the great moment had arrived. The group tied their balloons to the parapet, shot off their cap pistols, and, according to Sloan, “did sign and affix our names to a parchment, having the same duly sealed with the Great Seal of Greenwich Village.” Drick then read the declaration, said to be inspired by Duchamp, which consisted of the word “whereas” repeated like a rosary, and culminated in the declaration that “henceforth Greenwich Village would be a free and independent republic.”

Some say that the entire incident merely resulted in the permanent lock on the side door of the Washington Square Arch.

I beg to differ. That soused party comes to mind every time I see the great arch. I think of them whenever a kid with a guitar case asks me for directions to the park

I recall that party 100 years ago when I think of my old friend Phil Ochs, who wanted me to call him “John Train.” These days, the Smithsonian Institute sells CDs of Phil’s protest songs, and PBS calls him an American Master. Imagine seeing an exhibit at the Smithsonian, and he was your friend, and he still owes you two bucks!

I remember the Republic when I think of Ted Joans, who came to the Village in the late ’40s, roomed with Charlie Parker at 3 Barrow St., and started a business called “Rent a Beatnik” for suburban “squares” who wanted to have a party. Ted had dinner with Bird and James Dean at Bianchi and Margherita, around the corner on Fourth St., and told me he didn’t care what James Dean was like.

“He came here to see what we were like!”

Ted scrawled “Bird Lives” all over the Village when his friend died. He wanted to build a statue of Charlie Parker, 10 stories tall, straddling the Sheridan Square subway entrance, blowing that genius sax.

I remember the Republic of Greenwich Village as all of the greed around us tries to push us out of our homes, and out of our minds. As a new president of the United States is about to stand before the world and take an oath.

I am so very privileged to have lived for these many years in the Republic of Greenwich Village. No malignant glass tower can really change us. No dictator can ever fool us.

When there is injustice, we oppose it. When there is ignorance, we resist it. When there is art, we will receive it from the heavens as E.E. Cummings’ human antennae.

The centennial of the Republic of Greenwich Village is an important event to recognize. I might just stay home on the night of Trump’s inaugural, but on the evening of Jan. 23, 2017, I will walk over to the great Washington Square Arch, and place a candle in memory of our founders.

So that our Republic shall endure.