The city’s goal of reducing the reliance on emergency rooms by helping people take advantage of available preventative care is much easier said than done, medical experts said.

“It’s not easy to change individuals’ patterns of seeking care,” said Michael Sparer, chair of Health Policy and Management at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health. “There are large numbers of people who are on Medicaid, who have insurance right now, who rely heavily on emergency rooms for their care, so even if you have insurance it’s not a guarantee that you’re gonna stop using the ER.”

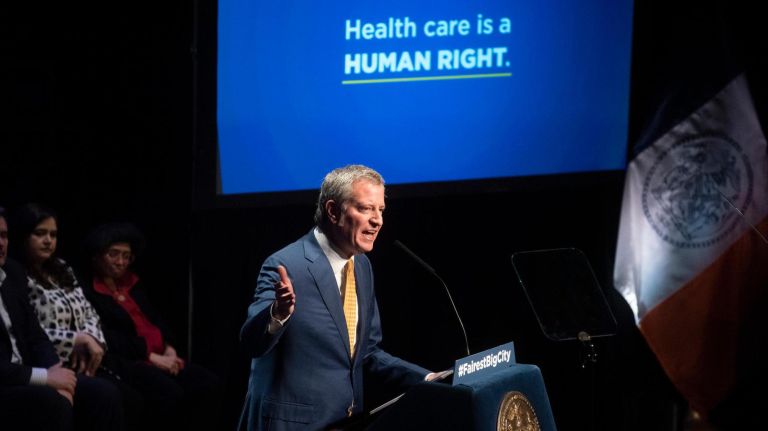

Mayor Bill de Blasio announced Tuesday that the city would launch NYC Care this year, with an effort to provide primary and specialty care to uninsured New Yorkers, regardless of their immigration status. The program will include a hotline to assist them in finding the care they need, and the cost of the care will be on “a sliding scale,” based on a person’s income.

The program is likely to be successful in getting more people to take advantage of the care available to them, said Sherry Glied, dean of NYU’s Robert F. Wagner Graduate School of Public Service.

“I think what it’s going to do is encourage people to at least think of themselves as having coverage,” she said. “We know that when people do that, that actually increases their use of care.”

But that doesn’t equate to the number of emergency visits going down.

“It is the right idea, but operationally it is much harder to do,” said Adam Block, an assistant professor of public health at the New York Medical College. “To assume that that is going to happen is a very strong assumption.”

Glied agreed, pointing out that “uninsured people actually don’t use the emergency room any more than insured people do. They just don’t use anything else.”

In fact, expanding health insurance in other places, such as Portland, Oregon, increased the use of emergency rooms, according to the Oregon Health Insurance Experiment.

“Medicaid increased visits occurring during both standard hours (weekdays) and outside of standard hours (weekends and evenings) by over 40 percent,” the authors of the study said. “We also found no evidence that Medicaid caused new enrollees to substitute office visits for ED visits; if anything, Medicaid made them more likely to use both.”

Part of the reason emergency visits don’t decrease with more access to preventive care could be wait times for appointments, the medical experts said. It was not immediately clear what capacity Health + Hospitals, the city’s public hospital system, has to treat more people through the NYC Care program.

Currently, the wait time for primary care appointments is within a week, H+H President and CEO Mitchell Katz said.

“The commitment of this administration is as more and more people join this program, we will maintain that – within a week or two weeks, everyone will have access to a primary care doctor,” he said at a news conference Tuesday.

He was not as specific about specialty care appointments, but he expects wait times to be shorter by the time people enroll in NYC Care, expected by this summer.

The experts agreed that working to get more people primary and specialty care is a good thing, but questions remain about how it will be accomplished, and it isn’t likely to solve the problem of overuse of the emergency room.

But for de Blasio, the announcement of the program was probably part of a bigger picture.

“As a statement of public policy, it was a strong statement from the mayor in support of principles that he believes strongly in,” Sparer said.