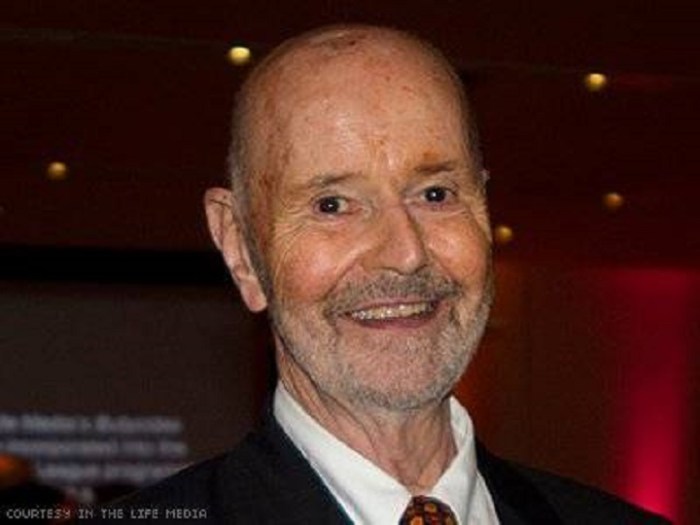

In a dimly-lit room with racks of women’s clothing, Ghanaian artist and LGBT+ activist Va-Bene Elikem Fiatsi flipped through photo self-portraits illustrating her transition to womanhood.

Transitioning is not illegal in Ghana, but it will become so if a new law is passed, intended to tighten already strict anti-LGBT+ regulations which render same-sex relations illegal.

Homophobia is pervasive in the West African country and trans people are generally considered to be gay.

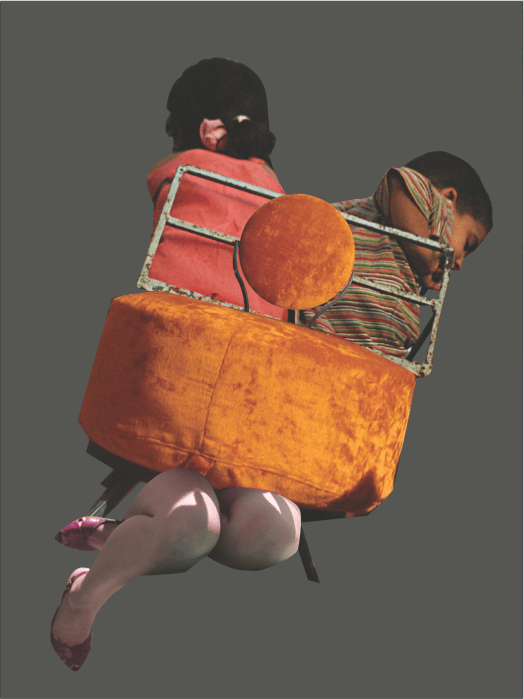

Fiatsi first exhibited the photographs, dubbed “Rituals of Becoming”, in 2017. Supportive audiences flocked to see the show in Ghanaian galleries.

Her work reflects how LGBT+ people in Ghana have navigated legal and social constraints to carve out a space to express their identities.

But Fiatsi fears that even that limited space could now be closing with the new bill, which if it passes would see her risk prosecution every time she puts on a dress.

“To say I’m afraid is an understatement, but I am what I am,” said Fiatsi, who runs an artist residence in Kumasi, Ghana’s second city.

“It feels like waiting to be slaughtered,” she said.

Ghana is one of more than 30 African countries that outlaw same-sex relations. Guilty verdicts carry up to three-year prison sentences.

A group of lawmakers from Ghana’s opposition introduced what they called a “Family Values Bill” in November, which would impose jail terms of up to 10 years for advocacy of LGBT+ causes and between three and five years for those who “hold out” as lesbian, gay, non-binary, transgender and transsexual, or who undergo or perform surgical procedures for gender reassignment.

The bill, which has broad backing among lawmakers but has yet to be voted on, also includes a provision that would force some to undergo conversion therapy. Amnesty International said this could violate Ghana’s anti-torture laws.

No politician has come out publicly against it. President Nana Akufo-Addo urged civil debate and tolerance when the bill was introduced but did not take a stance on its content.

Opponents say its passage would be a major setback for a country whose reputation as a friendly and stable democracy attracts tourists and investors.

Its backers say LGBT+ activities threaten the concept of family which is central to the structure of all Ghana’s ethnic groups. No voting date has been set.

“I call it the ‘Anti-Human’ bill,” said Fiatsi, who is a former Christian pastor. “It takes away from our family values of being a tolerant country, and being hospitable and loving.”

“WE ARE ALL THE SAME”

There have been no national opinion polls on the bill. Advocates say LGBT+ people are often subject to physical abuse and blackmail in Ghana, and those who come out or are outed are frequently ostracised by friends and family.

“There are some of my siblings and cousins who, for over five years, we never spoke, even though I love and miss them so much,” said Fiatsi. “Most of them think I’m just a demon.”

So do many of her former colleagues. Christian leaders have been among the most outspoken champions of the bill.

When public hearings began in November, Abraham Ofori-Kuragu, a spokesperson for the influential Pentecostal-Charismatic council, said he had never seen a law “so bold in its presentation of the Ghanaian agenda.”

More than 70% of Ghana’s 30 million people are Christian, and billboards with the faces of popular preachers adorn most street corners in the capital Accra. Some faith leaders condemn advocacy for LGBT+ rights as a Western imposition.

No longer welcome at the churches where she used to preach, Fiatsi channels her evangelism into art and activism.

Her studio compound, where she hosts LGBT-friendly artist residency programs, is filled with sculptures carved from tree trunks or shaped from old electronics. Murals and affirmations like “We Are All The Same” line the walls.

She has a global network of allies but she insists she will stay in Ghana out of solidarity with those unable to leave.

Even as the perils of life as a trans woman rise, Fiatsi takes comfort in small acts of humanity.

Shortly after the bill was introduced, she traveled for a funeral to her family’s village, her first time back in 20 years.

She stood nervously in her dress and heels. Some people exchanged pleasantries, while others darted their eyes and quietly sniggered.

Before too long, the awkwardness gave way to familial warmth. A relative patted her back. Another asked how life was going. When someone made a snide comment, Fiatsi playfully stuck her tongue out before continuing her conversation.

“There are many more of us that will be born, even far after I’m gone,” she said. “What I do today is not for me, or even for those living today. It’s for the future generation.”