BY ZACH WILLIAMS | Predicting what life will be like in the future is a tricky business — one that often involves scenarios residing on the extreme end of the sci-fi spectrum. We will not live underground to escape the effects of nuclear winter, nor will we be vacationing on the moon. Those who envision flying cars or other truly transformative technologies should glance at the Empire State Building and note that airships never took to the docking station up top.

Although many things will change in the next 25 years, the means by which we move around Midtown does not appear to be one of them. In many respects, the dominance of the automobile is ending in favor of railways, buses, bicycles and good old-fashioned walking. Four wheels (and some extra ones for buses) or two legs are still the best means we have. In respect to public transit, however, we are already seeing the future unfold in forms likely to hold for decades, especially given the length of time required for major infrastructure projects.

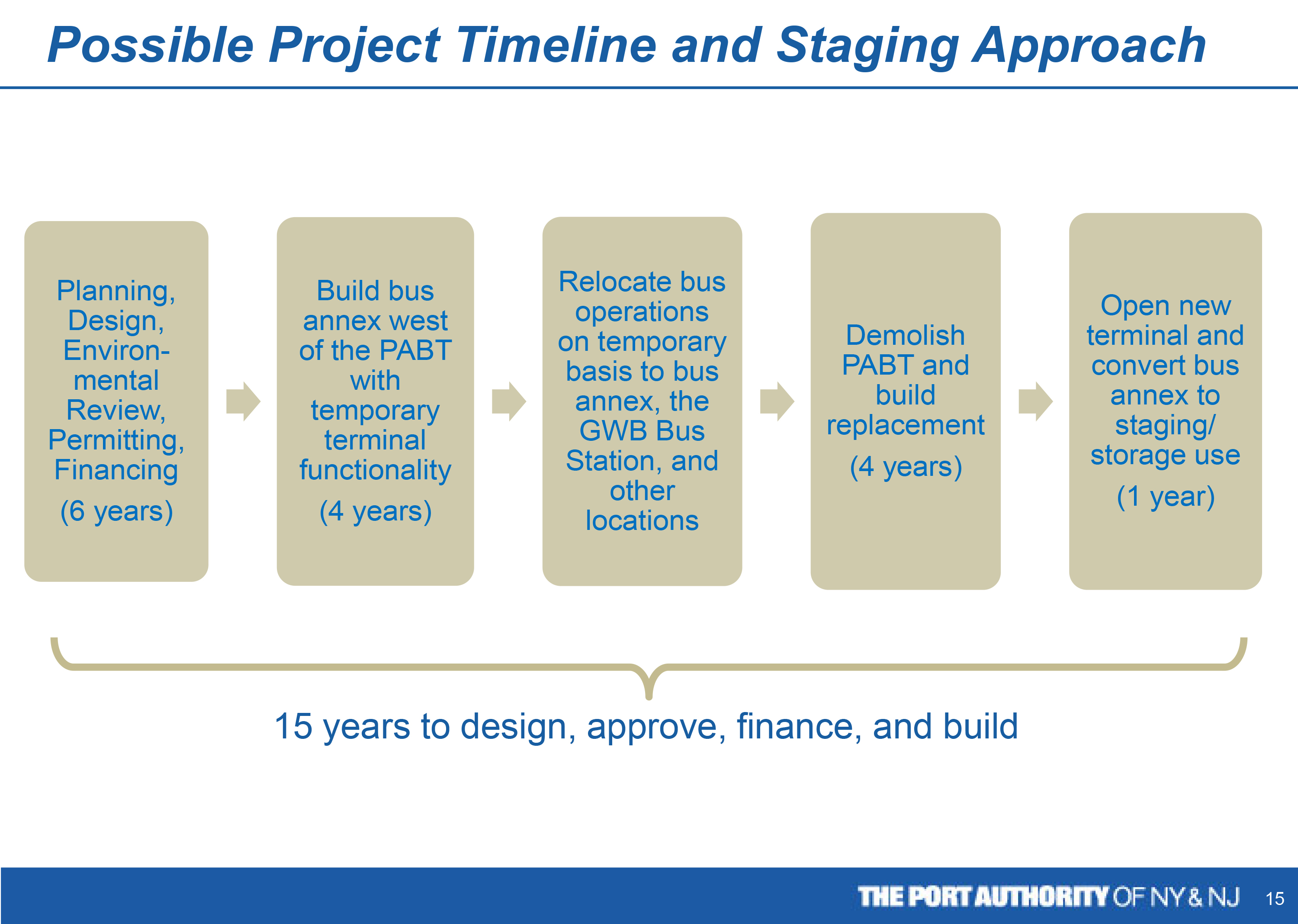

The Port Authority began the planning process for a new Midtown bus terminal this year. The shortcomings of the current 50-year-old facility are well-known and fundamental. It is too small and will fall apart in the coming decades from age, and the bigger modern buses. If all goes well, a replacement could open in about 15 years with accommodations for the 1,000 buses (each weighing 27 tons) per hour estimated to be in motion during the evening rush period of 2040 — a nearly 25 percent increase from current levels, according to a March 2015 Port Authority presentation on the plan.

Five concepts for a new terminal were included in the presentation. Their prices vary from $7.5 to $10.5 billion. The more high-rise development space they include, the lower the price. The cheapest option would not even fully accommodate commuter passenger demand, while intercity buses would only find a home within the priciest design. A future Hell’s Kitchen free from bus congestion on neighborhood streets depends on the decisions of which way to go, but the Port Authority is not the only entity looking to shake up the local streetscape.

Rail travel was left for dead at about the same time that the current bus terminal was built. Former parks commissioner and “master builder” Robert Moses was busy reinventing the city for the needs of the automobile. His efforts to lay express freeways across Manhattan ironically catalyzed the historical landmarking process, which ensures that much of old New York City will survive well into the current century.

The future Moynihan Station (at the former Farley Post Office building at Eighth Ave. btw. W. 31 & W. 33rd Sts.) will not be the rebirth of the old Pennsylvania Station per se — but a certain amount of irony, if not karma, could be at work. Beaux-Arts architecture will have its niche in mid-21st century transportation, even if we’re stuck with the current Penn Station for the time being.

Meanwhile, another historical throwback is in the works. An ongoing effort has the goal of replacing private automobiles on 42nd St. with a modern take on the trolley line. Such transportation was the norm on the street until 1946. The City Council voted to support the plan in the 1990s, but funding was not available.

The effort continues 20 years later through the “Vision 42” initiative, whose supporters meet on the third Tuesday of every month. As they wait for political support to gain traction, their website (vision42.org) is filled with technical studies of the project and renderings that depict Midtown Manhattan with a low-floor light rail line running river-to-river along 42nd St.

Advocates say that the economic benefits of such a transformation would exceed the costs of constructing 2.5 miles of trolley line (estimated at $360 to $510 million). Four prospective designs were selected last year, all of which propose a mixture of a pedestrian mall and light rail system. Former traffic lanes would become space for outdoor vending, an idealized recreation of the busy commercial streets of a century ago. Advances in fuel cells would make the trolley cars self-propelling rather than reliant on overhead wiring, and help reduce overall costs. Underground utility pipes and wires could complicate construction, but the barriers to light rail on 42nd St. are largely of a political rather than engineering nature. If all parties got on board, particularly business and building owners along the route, the project could be realized in just a few years.

Chances are high that this project will happen long before the Second Ave. subway nears completion. Some things might just never change. As always, funding remains the big determiner of any subway system extension, especially when compared to the relatively cheaper costs of surface rail systems. The dream of a 7-train extension to New Jersey could remain just that in 25 years, given the current pace of subway construction projects — but the current citywide emphasis on pedestrian safety might be the biggest threat to the century-long dominance of the private, gasoline-burning automobile on city streets.

The city is aging fast. City estimates state about a 44.2 percent increase in the senior population by 2030. There might be an old-timer taking his internal combustion engine out for a spin on Ninth Ave. on the pleasant afternoons of 2040, but that likely won’t be the only peculiar feature of his car. With drones buzzing throughout the skies, toting parcels from here to there, the sight of a car driven by a human might appear antiquated. Self-driving cars are already under development. The predicted advancement by mid-century of artificial intelligence on par with our own would enable this transition away from a dependence on human drivers with all of their potential for accidents. Computers are already better than us at “Jeopardy!,” chess and piloting jets, after all. They can even write a rudimentary news story.

An aging generation (by 2040) born in the 1980s and early 1990s also portends less reliance on automobiles of any type. “Driving by young people decreased 23 percent between 2001 and 2009,” the New York Times reported in a 2013 article entitled “The End of Car Culture.” The ongoing Vision Zero initiative emphasizes less car use through the implementation of “Complete Streets,” which allocate space on more equal terms among buses, cars, pedestrians and bicyclists whose numbers have doubled in the last five years across the city, Chelsea Now reported last December.

The Ninth Avenue of 2015, the first local street to receive such a redesign, will likely be the paradigm of the coming decades as car ownership decreases and local transportation options expand. Crosstown trips in 2040 will involve plenty of walking if the trains are too full or no bicycle is at hand. Taxis might get a little held up as the trolley rolls along 42nd St. Although digital technology will have changed our lives in as many different ways as it already has in the last decade, the transportation means of the early 20th century are here for the long haul.

Going anywhere in Manhattan will still take that standard 15 to 30 minutes. But it will be sleeker, a lot safer, and perhaps a little bit quicker. The big technological leaps will likely arrive from elsewhere and affect different facets of daily life — but you probably have many more years to save up for that moon vacation.