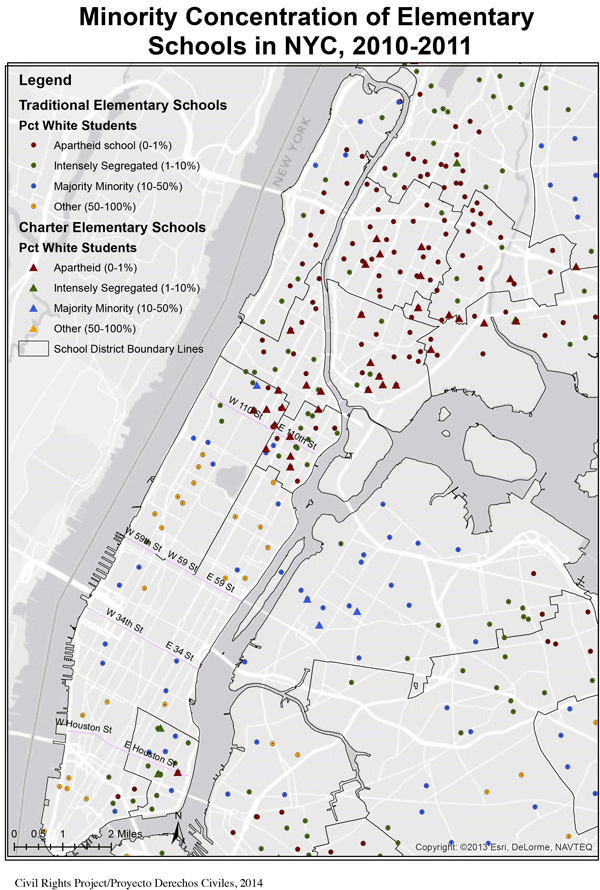

BY ZACH WILLIAMS | News coverage about a new report on severe segregation in New York City public schools has focused on lack of student diversity in schools in Harlem and the Bronx. However, the report also noted another area where school segregation is particularly heavy, though it has received little media coverage: the East Village and Lower East Side.

In short, policy makers — by decreasing emphasis on maintaining classroom diversity while increasing support for alternative education models — have created the highest levels of separation along racial and economic grounds in Manhattan south of Harlem, according to a March 26 study by the UCLA Civil Rights Project.

While some public schools in the East Village and Lower East Side’s Community School District One have seen increased integration in recent years, minorities comprise more than 90 percent of the students at a dozen other elementary schools in the district, according to the researchers.

The district is bounded by E. 14th St., the East River and Fourth Ave., Delancey and Clinton Sts.

“The ending of the diversity-based admission system in [Community School District One] of the Lower East Side is a prime example of the effects of a free or so-called colorblind school choice policy, as the area has experienced rising school resegregation ever since,” the report states.

Increased funding in the state budget for charter schools — 97 percent of whose students in Manhattan are minorities, according to the study — has sparked the ire of district educators, who charge that such schools threaten the funding base and diversity efforts of traditional public schools.

Governor Cuomo, in a March 31 statement, touted an increase in the budget of per-student funding for charters of $250, $350 and $500 in upcoming consecutive years.

Eligibility for the newly approved universal pre-kindergarten program and new access to funding to provide space for charter schools will also promote the schools through the budget, Cuomo noted.

In the wake of the end of civil rights-era integration efforts, such as busing and consideration of race in school admissions, charter schools have been offered by policymakers, such as former Mayor Bloomberg and Cuomo, as a chance for students from disadvantaged backgrounds to get a better education.

“That’s the mythology they are perpetuating,” said Lisa Donlan, president of Community Education Council District One.

The city’s Department of Education did not respond to requests for comment on the issue of the district’s racial segregation.

According to a study the C.E.C. released last fall, white students and racial segregation have simultaneously increased within District One. The phenomenon is enabled due to the district’s unzoned nature. Similar to only two other districts in the city, District One allows its students to enroll in schools throughout the district regardless of their residential address, Donlan explained.The white population residing within the school district has increased by 14 percent in recent years, and is now at 32.4 percent. Correspondingly, white students in 2011 comprised 16.6 percent of district students, an increase of 10 percent from 10 years before. Among 23 district schools, four were more than 40 percent white while 15 schools had less than 10 percent white students, according to the C.E.C. study.

The P.S. 188 building on E. Houston St., which houses four schools, includes the Island School, which is 96 percent minority, and Girls Preparatory Charter School, whose students are 99 percent minority. The charter was labeled an “apartheid” school by the UCLA study. The fifteen public schools, plus several charter schools, with less than 10 percent white students were ranked only slightly better on diversity, earning the label “intensely segregated.”

Such discrepancies represent an education system that neglects diversity when determining a school’s relative success, according to Donlan.

“There has been a sense over the last 10 to 12 years that separate can be equal, but in my experience that has not been true,” she said.

Attending schools fully representative of local communities has been known to raise performance among all students, regardless of personal family income, the UCLA study noted. Among that study’s policy recommendations were the implementation of civil rights standards in education policy, as well as greater efforts at ensuring equal access to school choices for low-income families. Poorer families, more often than their wealthier and white counterparts, lack the means to negotiate the complicated public school enrollment process, the study notes.

“The concentration of poverty in a school influenced student achievement more than the poverty status of an individual student,” the UCLA report states. “This finding is largely related to whether or not high academic achievement, homework completion, regular attendance, and college-going are normalized by peers. This correlation stems from relationships established with other students as well as teachers.”

P.S. 363 — The Neighborhood School, on E. Third St. — has a white student population of 43 perccent. It has yet to receive a response from D.O.E. for the school’s programs aimed at increasing student diversity through “a set-aside admission program for low-income students and English Language Learners,” the study noted.

Principal Dyanthe Spielberg and about 20 of the school’s students and teachers were among hundreds who demonstrated in Midtown on April 10 against Cuomo and the increased support for charter schools.

“It’s about reflecting the community of the Lower East Side,” Spielberg said.

New groups are still arriving in one of the most historically diverse neighborhoods in New York City. But some longtime L.E.S. residents worry, not about the intentions of incoming immigrants from China and Central Asia, but rather about the inflow of white residents accompanying the area’s ongoing gentrification and development, who they fear will push out poorer minorities.

However, one local resident of 42 years recalled a time when the government was the instrument of greater cultural understanding through bold integration efforts. “I remember getting off the bus,” said Bradshaw Liddie, a community advocate who was among the first black students to integrate an Upper East Side high school in the 1960s. “It needs to be diverse,” he said.