BY JOSH ROGERS and DUSICA SUE MALESEVIC | Mayor Bill de Blasio said last week he had no “philosophical” objections to a tower adjacent to a historic district, so perhaps it was not so surprising that Howard Hughes Corp. revealed that its long-awaited revisions to the firm’s Seaport development plan still includes a tower, and now meets another administration goal: affordable housing.

The tower was originally 650 feet and it has been reduced to 494. The Seaport Working Group, made of local politicians and community leaders, had been waiting since June, for the firm’s revisions after it released its guidelines and principles, calling for an alternative to the tower.

Manhattan Borough President Gale Brewer and Councilmember Margaret Chin, two of the group’s leaders, both blasted the new plan in prepared statements released Wednesday night, minutes after Hughes presented the plan at a private meeting of the group.

“It’s clear that the Howard Hughes Corporation has not fully considered all of the guidelines put forth by the Seaport Working Group,” Chin said. “I can’t support the proposed tower in its current form, and I can’t support the development proposal overall in its current form.”

At a press conference the next day where a model of the site was revealed, David Weinreb, C.E.O. of Howard Hughes Corp., was asked to address Chin’s criticism.

“We’re very hopeful that as our proposal gets out into the community … We believe that they’re going to welcome our proposal and that those voices will be heard by the political people like Margaret Chin and others,” said Weinreb. “We’re hopeful that as the support grows for the project that she’ll reconsider her position.”

The plan revealed several community benefits that includes $171 million dollars to rebuild decaying infrastructure, such as the piers, the moving and restoring the Tin Building and the expansion of the East River Esplanade. The tower will house a public middle school and there will be a marina, enhanced waterfront access, as well as financial support for the Seaport Museum that will be upwards of $10 million.

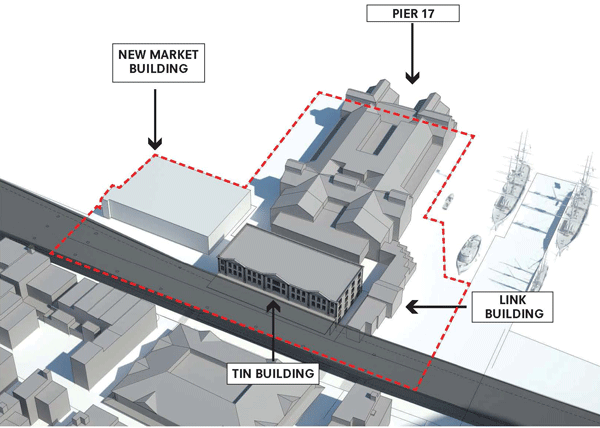

It includes affordable housing along with the tower, which would be built where the New Market Building is currently located, just north of Pier 17. There would be around 70 apartments at below market rate, and 150 at market rate.

About 30 percent of the units would be affordable, and they would be built near Schermerhorn Row, something which was first reported by the Wall Street Journal.

Weinreb said that Howard Hughes has addressed the Seaport Working Group’s guidelines.

“We addressed every single one of the important priorities that they laid out for us in that group,” said Weinreb. “In some cases, we’re able to accomplish a 100 percent of what they wanted and in some cases we were able to partially give them what they wanted. But in all cases we addressed every concern.”

The height of the tower has been the point of contention and Gregg Pasquarelli, principal architect of the project and a partner with SHoP Architects, said that a shorter, wider building would have a bigger impact on the street than the slender building that is being proposed. The base of the proposed tower is much wider at its base and then gets narrower at its top.

“When we thought about the new building, we said what’s the best way to be a good neighbor,” said Pasquarelli. “The first thing that we wanted to do was not have the wide end facing toward the district, but to turn it so that the narrow end was facing towards the district. We started to think how to sculpt and shape the building so that light plays off of it and that it has a sort of thinning effect.”

“We know it’s a tall building but it’s really the driver for getting all these other community benefits,” said Pasquarelli, adding that no resident’s view of the Brooklyn Bridge will be blocked by the tower.

The mayor had signaled what was to come at the Seaport in response to Downtown Express questions last week at a Nov. 12 press conference in Lower Manhattan.

“I don’t have any philosophical prohibition in my mind about putting a tower next to a historical district — this is New York City,” he said. “Throughout this city we have some extraordinary modern buildings right next to historic buildings….

“By the way it’s all case by case. The attitude we’re going to take — I said before we need to have much more affordable housing. In some cases that’s going to take taller and denser buildings, but it’s always about the specific site.”

Affordable housing has also been a high priority for many of the tower opponents, but they have made it clear it would not be enough to win support.

“That may be fine for the administration but not for the community,” John Fratta, a working group member and chairperson of Community Board 1’s Seaport Committee, told Downtown Express earlier in the year. “It’s still a tower and it just doesn’t belong.”

The New Market Building is just outside the South Street Seaport Historic District, but it was a part of the old Fulton Fish Market, and preservationists have tried in vain for many years to landmark it.

The working group guidelines treated it as part of the district and the Hughes firm all along has said that it supports the working group.

“It was a very good process,” Chris Curry, the Hughes executive in charge of the project, said last week. “I actually think we’ll have a better project because of it.”

A source opposed to the current plan said Wednesday night’s meeting was civil, but both sides understand it’s time to “play hardball.” The plan is likely to undergo more revisions given the initial negative reaction from the local politicians.

Curry had claimed back in January that the original building’s height was 600 feet, but a source sympathetic to Hughes said Wednesday that Curry was incorrect and that the building had actually been 650 feet, meaning it has been reduced by over 150 feet.

“Our plan preserves the historic district, repairs crumbling infrastructure and delivers the benefits the community has called for: waterfront access, a middle school that could also serve as a community center, affordable housing, funding to save the Seaport Museum and tall ships, and a fresh food market, among other things,” Weinreb said in a prepared statement Wednesday night. “The plan represents a more than $300 million investment in public benefits for Lower Manhattan…. We are proud to have the support of Lower Manhattan families and small business owners who know that the only way to truly save the South Street Seaport is to invest in its future. We are confident that as more residents learn about our plan, they will embrace it.”

For her part, Brewer, in her statement, said: “Historical context, building heights, and maintaining the vitality of the area are all elements which must be factored in to any final project in this crucial Manhattan neighborhood — the neighborhood where, in many ways, New York City began. As I’ve said before, building a tower at the South Street Seaport is like building a tower at Colonial Williamsburg.”

Although there is strong neighborhood opposition to the tower, it’s far from universal. There appears to be a large minority which is sympathetic to the tower, or at least more interested in negotiating community givebacks rather than reducing the building’s size.

A few mothers stopped last week to speak to Councilmember Chin after a “town hall” meeting.

One of them, Amanda Byron Zink, also a Seaport resident and small business owner, said, “there’s a large number of residents who are not being heard. We’ve heard rumblings of a school a community center space, a green market.”

Zink said she’s also expecting the project will attract more and better stores to the neighborhood.

“I want to stay in the South Street Seaport [to shop],” she said. “I don’t want to go to Brooklyn anymore. I don’t want to go to Battery Park City anymore.”

Before being built, the plan would need to receive Landmarks Preservation Commission approval. Brewer and Community Board 1 would make a formal advisory opinion before it would go to Chin and her Council colleagues for an up or down vote.

Although tower opponents could not have been heartened by some of the mayor’s remarks last week, they were no doubt pleased to hear de Blasio’s strong support for another working group goal — keeping the South Street Seaport Museum afloat in the face of financial difficulties.

“I think the Seaport Museum is really crucial to the city and I think it has to be protected because this is how New York City became New York City,” de Blasio said in response to this paper. “We’re here because of the water, because of the maritime industry and I think it’s really important future generations feel that — so protecting the museum in some form is something I care about a lot.”

A VERSION OF THIS ARTICLE APPEARED IN THE NOV. 20 – DEC. 3, 2014 EDITION OF DOWNTOWN EXPRESS. Read the online version posted Nov. 19, 2014.