Amid New York City’s housing crisis, many small landlords are feeling the pinch of rising maintenance costs, uncooperative tenants and what they view as a lack of support from city and state agencies.

While the city’s rental market is often associated with high-rise towers and corporate landlords, small landlords still account for a significant share.

Real estate experts told amNewYork that an estimated 30% to 50% of the market is owned by small landlords, defined as owners of buildings with 10 units or less. “Mom-and-pop” landlords who own just a few buildings are also common. Shortly before the pandemic, the housing data website justfix.org reported that 28% of New York City’s 2.3 million rental units were owned by landlords with between one and five buildings.

New York City has long maintained a host of tenant-friendly laws, shaped by a history of notorious absentee landlords with large property portfolios often plagued by housing code violations—and, in some cases, linked to fatal fires, structural collapses, and other tragedies.

But some argue the pendulum has swung too far in tenants’ favor, placing burdens on small property owners that discourage them from renting out their homes — ultimately reducing the supply of reasonably priced apartments.

Amid the push for increased tenants’ rights, small landlords say they feel no one is advocating for them, even when their tenants turn out to be disastrous.

The struggle for landlord housing aid

For instance, Marisol Owen’s story, in which she struggled to get rent from a delinquent Bronx tenant for years and said she received little help from city agencies, highlights systemic challenges that can deter property owners from renting out units.

Owen and her husband Steffan rent out a three-family house in the Bronx. They grew increasingly frustrated with one of their tenants, Wesley Linares, who stopped paying rent in June 2021 after failing to renew his city-funded rental subsidies.

By the end of 2022, Linares owed over $31,000. But after Owen called every organization, elected official and city agency she could think of, no one could help resolve the situation beyond advising her to start the eviction process against Linares, which she hoped to avoid. At times, Owen said she was essentially told, “We only help tenants.”

amNewYork reached out to Linares via email and has not yet received a response.

Owen, a social worker, said she suffered from depression and increased anxiety and spent fruitless hours every day on the phone looking for help.

“I’m invisible as an individual,” she told amNewYork in January 2023, when she reached out in hopes of amplifying the plight of small landlords.

Advocates for small landlords argue that the city needs to better balance the rights of property owners and tenants in order to maintain the supply of existing housing.

Ann Korchak, board president of the grassroots advocacy organization Small Property Owners of New York Inc. (SPONY), told amNewYork that the city really needs small landlords like Owen to stay in the rental business because they are an important source of “naturally-occurring affordable housing.”

Korchak said SPONY keeps in contact with about 700 owners, many of whom are renting out a property passed down through generations. They usually charge modest rents and prioritize finding the right tenants, especially in situations where the owner remains living on the property. Since small landlords often find renters via word of mouth, they can help form “immigrant enclaves” and create strong communities, said Korchak.

If “mom-and-pop” owners stop renting, it would be a huge loss for a city that needs to keep every bit of housing it has. “These small owners are crucial to the housing market,” said Korchak.

Nowhere to turn

Owen said she never expected major issues when renting out their home at 886 Fairmount Place in the West Farms neighborhood, near Crotona Park.

When she and her husband purchased the property 11 years ago, it had a history of housing stable, long-term tenants. One was living there when the Owens bought the house and remains there today.

One day in 2019, when the husband-and-wife duo still lived in the home, a woman Owen said was a private realtor knocked on the door. Owen wasn’t home, but the woman spoke with Owen’s mother and relayed the message that a person leaving a city homeless shelter was in need of housing. Owen later agreed to have him move into the second-floor unit, and she and her husband continued living in the house for about two more years before moving upstate.

Since Linares, who was 30 at the time, was coming from a shelter, he was entitled to a CityFHEPS subsidy. This subsidy typically allows the tenant to pay rent at no more than 30% of their income, while the voucher covers any remainder.

When Linares first signed on to live at the Owens’ house, CityFHEPS covered $1,250 per month, which later increased to $1,850. The city paid the first full year in advance, but when Linares’ annual CityFHEPS renewal came up, he did not submit the required application. Despite Owen’s repeated efforts to contact him, the city and even his mother, Linares did not keep up with the paperwork and was eventually dropped from the system.

According to the renewal application, if he had stayed in touch with case workers and submitted his CityFHEPS renewal—even if a year late—he likely would have been able to restart his benefits.

The city sends out CityFHEPS renewal reminders five months prior, two months prior and two days prior, according to a spokesperson for the Department of Social Services (DSS). About 90% of the city’s 55,000 voucher holders successfully renew when needed, and those who drop off enrollment are usually those who move out of the city, become income ineligible or pass away, the spokesperson said.

Unfortunately, Linares became one of the few who fell through the cracks.

A ‘divisive’ system

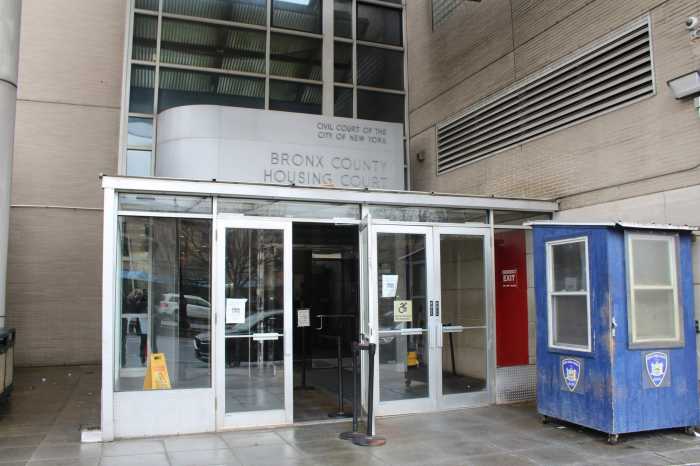

Owen said she suffered emotionally and financially throughout the long legal process that ensued as she and her husband finally started a nonpayment eviction against Linares in October 2023. The rent ledger submitted to Bronx Housing Court shows that Linares did not pay rent for 27 months between July 2021 and October 2023 and owed a total of $49,950.

Despite the obvious nonpayment issue, Owen said she was treated like the bad guy when calling city agencies and elected officials. She called the system “divisive,” pitting tenants against landlords even when the tenant is clearly at fault.

Owen said she was empathetic to Linares’ need for extra help in following up on his responsibility. She herself has fairly severe ADHD and struggles to keep up with paperwork, she said.

But as much as he was struggling, she was too — from the loss of income and from the daily stress of trying to manage the situation.

“What about the small landlord who’s also marginalized?” Owen said. “They have to be fair to both parties.”

Owen said she had to take time off from her job because her anxiety grew to be unmanageable. The longer the process dragged on, with the courts giving Linares at least three chances to renew benefits, the more she said she felt ignored.

Elected officials told her there was nothing they could do, and Owen said she believes some offices blocked her calls as she repeatedly tried to reach them to discuss her rights as a property owner with a nonpaying tenant.

“I felt like I had nowhere, I had to navigate everything,” she said.

‘Housing court limbo’

Korchak, with the small landlord group SPONY, said the city put Owen “in an impossible situation.”

As Owen discovered, New York City housing courts are strained with over 150,000 new cases each year, according to the Manhattan Institute for Policy Research.

That means owners can wait years in “housing court limbo” without knowing when or whether they’ll recover any of the lost money — and by the time they even move to evict, they’re typically owed six months or more of back rent, said Korchak.

“Once you’re in housing court, you’ve already lost,” she said.

Korchak agreed with Owen that the city does not do enough to support landlords, especially small ones who lack staff to help with administrative tasks.

Beyond nonpayment problems, keeping up with the city’s housing code is yet another challenge. Korchak said small owners have few resources to lean on when trying to comply with requirements that can be confusing to inexperienced landlords.

Owen had a few such experiences. She said there was once a boiler leak in the rental house, and she misunderstood the requirements to resolve the Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD) violation and ended up being docked three months’ rent. She also got hit with a violation last year for failing to mail in the paper copy of the rental renewal to HPD after completing the form and paying the fee online.

While landlords struggle to keep up with regulations, tenants are often told to go straight to HPD with any and all problems, which can result in bogus complaints, said Korchak. “HPD has been weaponized against us.”

In addition, tenants often have more built-in protections than landlords when cases end up in housing court.

For instance, the city’s right to counsel program — which guarantees legal representation in eviction proceedings — only applies to tenants, with “no recognition there” for the landlords who are also financially strapped, according to Korchak.

“There are no resources for us. We’re just told to suck it up,” she said.

She believes the city’s already strained housing system will only become worse if small property landlords—feeling abandoned by the legal system and overwhelmed by financial losses—choose to exit the rental market altogether. Without these “mom-and-pop” landlords, many of whom offer below-market or flexible rents to long-term tenants, New York risks further reducing its stock of affordable housing, pushing more renters into increasingly competitive and costly alternatives.

Building new housing takes a long time, and as more development occurs, “You can’t crush the people that can actually house people while you build more housing,” said Korchak.

Cash for keys

Today, Linares is still living at 886 Fairmount Place, as the courts gave him multiple chances to re-enroll for housing subsidies. He finally re-registered for CityFHEPS, and Owen said she now receives the correct rent each month.

Although the Owens did receive a substantial portion of Linares’ back rent — some from the COVID-era ERAP program and some from CityFHEPS — Owen said she believes she is still missing about a year’s worth.

More than anything, she said she wants Linares to move. She wants to rent the apartment to a close friend, who is seriously ill from kidney failure and left a nursing home to live upstate with Owen and her husband. If the friend could take Linares’ apartment, the two other renters in the house, both healthcare workers, could potentially help look after him, she said.

“I would love my money, but I also want [Linares] out,” said Owen. She plans to notify him this fall that she will not renew his lease come winter.

Korchak said it’s common for owners to resort to what she called a “cash for keys” arrangement, simply paying their tenant to leave.

But the problem compounds itself: landlords who have a negative experience often become “risk averse,” sitting on vacant units until they find “the perfect situation,” she said.

Many get to the point where they say they’ll never rent again — and if small owners end up selling, the property is more likely to be destined for corporate takeover instead of, for instance, being purchased by an immigrant family in need, Korchak said.

Losing any of these relatively affordable apartments would be bad news for the city, which has a “moonshot goal” of creating 500,000 housing units over the next 10 years.

“Having another unit come offline because the owner can’t get paid and the unit is left in statutory limbo means, yes, that is making our housing crisis worse,” said Basha Gerhards, senior vice president of planning for the Real Estate Board of New York (REBNY), in an interview with amNewYork.

Owen said she’s learned some harsh lessons as a small landlord. And she’s not alone: she said a neighbor to the Bronx rental house is having the same problem, renting to a couple with a Section 8 voucher who haven’t paid their portion of the rent in a year. The neighbor now wants to just pay his tenants to leave, Owen said.

Hypothetically, she said if she had a friend who wanted to rent out their property, she’d tell them to be “very wary” at best.

“And if my friend lived in the place, hell no,” she said. “You have no rights in your own house.”