By David Jonathan Epstein

Meng Dong remembered four years ago when as a 16-year-old he sat on the corner of a bed he shared with four strangers and peeled a banana. It was the second week in a row he had eaten bananas for breakfast, lunch and dinner. He used to love the taste. But now, as he choked down one more bite, he wondered why he crossed four countries to get to America. He wondered where the aunt that abandoned him in Lower Manhattan after only two weeks went.

Meng Dong is now 20 and goes by “Jack.” Five years ago his parents paid $50,000 for a smuggler to take him from China to the United States. He told his story to a reporter during several recent interviews.

Jack fared poorly in school in China and his parents were encouraged by success stories they heard from others who sent children overseas. But looking back, Jack realized the stories are just that: stories. His one piece of advice to a Chinese kid about to be smuggled: “Don’t come.”

But as a teenager Jack was encouraged by the aspirations of his mother. She, like many Chinese mothers who refer to America as “the Golden Mountain,” figured her son would soon make enough money to justify the expensive trip. Propelled by dreams of success, thousands of Chinese children enter the smuggling pipeline each year, and their primary target is the United States. The average U.S. income is about 20 times that even in large Chinese cities like Shanghai. But the higher wages in the states are accompanied by a higher cost of living. Many illegal-immigrant children who pay for the trip with promised work are hard-pressed to relieve their debt when making less than minimum wage.

Still, “reporting back failure to families in China is not a comfortable thing to do,” said Anita Gundanna, a Coalition for Asian American Children and Families worker. And Chinese families often bask in the pride of a child overseas, whether or not their prosperity is real.

Jack was 15 years old when he rode in a car with seven other people for two days from China to Vietnam. There the group stayed in a hotel with other illegal travelers, some as young as seven. A day’s travel to Cambodia followed.

At the Cambodian border Jack followed a guide. It was so dark he “couldn’t see his own hand.” A searchlight broke the ink-black night and swept into Jack’s peripheral vision. His guide waved an AK-47 at him and demanded Jack dive to the grass. He pushed his face to the dirt and waited. The light disappeared and Jack passed into Cambodia.

The success was short-lived. Cambodian army troops caught Jack’s group just over the border. Again Jack’s face was pushed to the grass, but this time, “the gun was directly pointed at us,” he said. “They told everybody, ‘Hands on your heads.’ I thought I was going to die, that they would open fire.” But the smugglers bribed the troops and the group continued. “Thank God. I’m too young for this,” Jack thought at the prospect of getting shot in the head.

He remembers sleeping on the floor of a hotel with other travelers. One of the men at the hotel with Jack was abandoned by his smuggler, or “boss.” The man had no way to pay for the hotel, so workers there beat him. “We heard him screaming,” Jack said. “We never saw him again.”

Some smuggled young women never get out of the hotels. Bosses sell them to hotel workers. “The boss will sell the girls for one night or whatever,” Jack said. “And they say all the beautiful girls stay there for two years, three years. And if they are very nice, they are never going to get out of Cambodia.”

After 20 days, Jack’s boss gave him a 24-year-old Japanese man’s passport. Jack took a train to Malaysia where he boarded a plane bound for Newark Airport in 1998. Airport officials in Malaysia sensed something amiss when Jack could not answer questions about his passport in Japanese. But his boss bribed officials at each turn and Jack boarded the plane.

On the plane Jack’s passport was checked by a flight attendant. The flight attendant alerted Immigration and Naturalization Service officials in Newark who came and put Jack in handcuffs.

Police transported Jack to a juvenile detention center in Pennsylvania. Jack does not know the name of the place because he could not read English at the time, but he does recall hating it. “Kids in the center had behavior problems,” he said. “They curse at you.”

Jack tried to use the phone to call the only contact he had in the states, but he forgot the number, and he dared not call his parents who back at home dreamed of his success.

Three days later officials transferred Jack to a center for nonviolent illegal minors in the Midwest. Jack spent five months there and befriended a diverse group of kids.

There are two ways out of the Midwestern facility Jack was in: deportation, or placement with a family member to await word on a green card. At the behest of his parents, whom he finally called, Jack’s aunt, Kuiying Lin, decided Jack could live with her. So facility workers escorted Jack to New York.

In a cruel break, Lin, in her late 70s, slipped in the airport in New York when she met Jack. The fall fractured her arm. Lin placed the blame on her newfound nephew. “Old Chinese people are very superstitious,” Jack said. “She thought I brought her bad luck and would get her killed.”

So after two weeks of cordial behavior, Lin left, she told Jack, to visit her daughter. But Jack never heard from her again.

Another two weeks passed and Lin’s landlord rented her apartment to a new tenant. So Jack had to leave.

Jack left for Pennsylvania to work in his father’s friend’s restaurant. The friend promised to get Jack into a local school. It was shortly after the Columbine shootings and Jack said the schools he visited did not want undocumented students. Still, the family friend assured Jack he would find a school, though in reality the friend stopped searching.

Frustrated, Jack contacted his former New York caseworker, Nancy Mei. Mei convinced Jack that his employer did not care about his schooling but only wanted cheap labor. Abandoned by his aunt and tricked by a family friend, Jack was despondent. He did not know whom to trust. “Friends or relatives, doesn’t matter,” he said.

Mei coaxed Jack back to New York where he claimed to live with a new sponsor, but actually stayed with four strangers in a roach-infested, $150-per-month studio apartment in Chinatown.

Then 16 years old, Jack could not get a job. So he lived for weeks at a time on only bananas and water.

Jack enrolled at Liberty High School at 250 W. 18th Street where he met Peng, another young immigrant. When Peng learned Jack’s situation he cooked Jack a dinner of eggs and potatoes. “It was the best dinner ever,” Jack said.

Jack then told Mei the truth and she moved him to a group home on the East Side. Again it was a home for children with behavioral problems. Jack, now dedicated to school, took an English dictionary and studied late into the night in the home’s kitchen.

That year Jack met a Taiwanese-American woman he identified only as Lin. She invited him to her house in Queens where Jack played with her kids, one 10 and the other 7. Lin became Jack’s foster mother and helped him write a letter to Congress about his educational progress. All of Jack’s teachers signed it.

The very next day Jack got his green card approval in the mail. “Right now you have an identity,” Jack said Lin told him. But Jack thought back on his journey as he held the card. “Is it worth it for just such a small card?” he asked himself.

By late 2001 Jack had settled into his new life. When disaster struck on Sept. 11, Jack feared for the lives of his new parents. His foster-father worked next to 5 World Trade Center, and Lin a few blocks away at Stuyvesant High School.

Jack did not hear from them for hours. “I thought maybe they had died there,” he said. “I thought, they have two little kids, if anything happens, I’m going to take care of them.” But Lin called hours later. “I said, ‘Thank God.’ I almost wanted to cry,” Jack said.

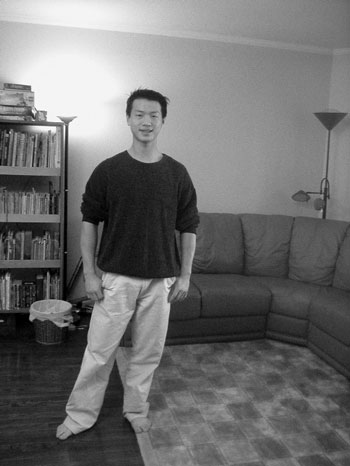

The sailing got smoother after that. Jack lives in Queens and works counseling mentally impaired youth. He is on pace to graduate from Queens College in 2005. He will be the first in his family to do so.

Despite his success, Jack dissuades others from his path. He said a culture of lies back in China keeps kids coming. Young immigrants “never tell people in China they are having a difficult time, only how good they are doing here,” Jack said. “They say they are getting fat even though they are bone.”

“Peoples’ life in China is based on socialization,” he said. “They ask, ‘How is your son doing?’ And they say, ‘Oh my son is doing so great.’ And that encourages everybody to come to the United States. Some guys think they are fat or ugly, but if they come here and make money, they can marry someone beautiful. Don’t come, just focus at whatever your current education is. There’s always ways to have a better future.”

Reader Services

Read More: https://www.amny.com/news/