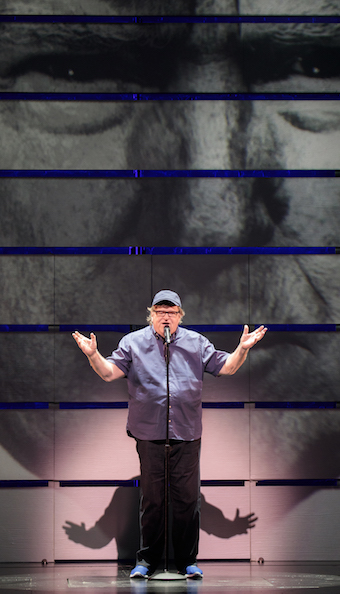

BY CHRISTOPHER BYRNE | Giving Michael Moore the benefit of every conceivable doubt, his Broadway foray “The Terms of My Surrender” has an ostensibly noble intent: to encourage people to believe that even one person’s actions can have an impact on society. That’s a serious premise. The problem is that in presenting it, Moore is not serious. Rather, he uses stories about himself and his own merry prankster past to spend two and a half intermission-less hours (apparently it varies every night) indulging in self-aggrandizement masquerading as agitprop.

One can hardly call this theater. Indeed, Moore has called the show a nightly political rally. If so, it’s a tremendously safe one. The Belasco Theatre is a closed environment with a self-selecting audience willing to pony up to $150 to have their liberal bona fides stroked by a celebrity. It’s understandable that he would choose such a place, given his harrowing stories of death threats and attacks from people who have been stirred to violence by Fox News, Glenn Beck, and others. But is it effective? Do his audiences go out into the night ready to man the barricades and fight? Or do they have a cathartic experience that validates their political angst and provides a kind of pressure valve for political anxiety?

That’s impossible to know, but I suspect given that activism often takes the form of raving on social media that it’s the latter. I’m afraid Moore has merely leveraged the character he plays and his celebrity to get people to pay for the kind of rants your crazy family gives you free on Facebook.

Three shows celebrating personal journeys, but only one powerful and poetic

Moore’s presentation and his whole persona have their roots in the Yippie movement of the late 1960s, which used comedy, theatrics, and then revolutionary exploitation of media to stage counterculture protests. Yet while the Yippies wanted to tear down structures to create an egalitarian utopia, Moore appears motivated by self-interest. He tells a long story about running for the school board as a result of being punished for a dress code infraction. His goal: get the assistant principal fired. His win — and becoming the youngest elected figure in the US — is driven by ego rather than ideology and is ultimately a smug and solipsistic account of gaming the system, the very thing he seems to decry in others. Moreover, it clouds his intended message. If gaming the system is morally right when you believe your cause is just, how can you honestly criticize those who do it now?

The show is a collection of set pieces and stories. Moore is at his best when he’s telling stories of his life. There is a protracted game show piece designed to show that Canadians have more civic knowledge at their fingertips than Americans. It’s a hackneyed conceit, and at the performance I saw it was hijacked by the audience participant, turning it into a painful and pointless exercise. In fact, Moore is unable to contain his guests. His interview section included the librarian who rallied others to save the public’s access to his 2002 book “Stupid White Men.” Aside from being more marketing than substance, Moore was incapable of reining her in and so she went on for a very long time. There are also plants in the audience who shout things out for Moore to respond to. That’s just cheap.

Now, I’m not disagreeing with much of what Moore said. The country — especially its political system — is in shambles in many respects. His story about the Flint water crisis is harrowing. Yet, though he tells you that he has the “real story,” nothing in his account hasn’t already been covered in the Times and elsewhere. And I do not agree with his statement that everyone who voted for Trump is stupid.

In his piece, Moore tries to style himself as a contemporary Will Rogers with a political bent. But his putative desire to motivate and validate his audience isn’t valor — it’s vaudeville.

“Van Gogh’s Ear” from the Ensemble for the Romantic Century, is, simply, sublime. Drawn from the letters of Vincent Van Gogh to his brother Theo and interspersed with art songs and chamber music from Fauré, Debussy, and other Romantic composers, the piece has a lyricism and simplicity that are emotionally potent and exciting.

The story, such as it is, follows Van Gogh through his tortured quest to paint and live, the severing of his ear, and his stint in an asylum. Through it all, the passion and torment of Van Gogh’s life are clear and beautifully understated, and the music stands in gorgeous counterpoint to his journey.

The simple set by Vanessa James is augmented by the inspired projections by David Bengali that splash the white set with color and poignantly detail the paintings, from which Van Gogh never made a dime, by the way. To see the brushstrokes magnified even as the painter struggles is brilliantly evocative and pure theatrical magic.

Carter Hudson is ideal as Van Gogh. It’s no easy feat to portray suffering, but what comes through in his finely nuanced performance is the spirit that leads inexorably to his tragedy. Chad Johnson as Theo Van Gogh has virtually no spoken dialogue (Theo’s letters in response to Vincent’s do not survive), but he is a thrilling tenor whose expressive singing conveys what we otherwise cannot know — the love and support Theo provided to his brother. Mezzo-soprano Renée Tatum plays Theo’s wife and the woman for whom Vincent cut off his ear. She, too, is spellbinding in her performance. The instrumental music is performed by a string quartet and piano.

Written by Eve Wolf and directed by Donald T. Sanders, this show envelops the audience in its poetry. I can’t think of any better — or more romantic and moving — way to spend a late summer evening.

Oh, dear. The exceptionally tiresome new musical “Curvy Widow” is the type of dreary exercise that pops up Off-Broadway with alarming regularity, fueled by ego and a large bank account. Bobby Goldman’s song of herself describes her sexual re-awakening after the death of her famous writer husband, James Goldman. She owned a successful construction company; he wrote the book for “Follies” and movies including “The Lion in Winter.” It’s a shame Goldman is gone because he might have given some substance to Bobby’s book, which is heavy on exposition but devoid of character and anything other than the most conventional comedy pulled directly from lesser sitcoms.

The basic premise is that Bobby, now a widow, decides to jump back into dating after umpteen years. Under the moniker Curvy Widow, she sets out on her quest for companionship and coitus. (Oh, and like Dolly Gallagher Levi, she’s waiting for a sign from her dead husband that she can get back into life.) Surprise! There are a lot of creepy guys online. Surprise number two: she’s got a trio of girlfriends to comment and support her. And here’s the big shocker (spoiler alert): Bobby discovers she’s just fine on her own.

Goldman’s turgid book is not helped by Drew Brody’s music and lyrics, which seem forced and a pale knock-off of Maltby & Shire, who covered similar ground with more substance in the 1980s. Small wonder this show seems like it came out of a time warp.

What keeps the sandman at bay, over and above the blessedly brief 85-minute running time, are the performances of the wonderfully talented cast. Nancy Opel leads the crew as Bobby, and her fine voice and comic skill give the material what life it has. The rest of the company plays many parts, and all are very good. In particular, Christopher Shyer and Elizabeth Ward Land stand out as appealing and funny and make one eager to see them in bigger, better roles.

Of course, it’s easy to sympathize with Goldman’s plight. Working out dating, especially at an older age, is a minefield, but that’s a fairly common observation. What it is not, at least in this case, is a workable musical.

MICHAEL MOORE: THE TERMS OF MY SURRENDER | Belasco Theatre, 111 W. 44th St. | Through Oct. 22: Tue. at 7 p.m.; Wed.-Sat. at 8 p.m.; Wed., Sat.-Sun. at 2 p.m. | $29-$149 at telecharge.com or 212-239-6200 | Two hrs., 30 mins., no intermission

VAN GOGH’S EAR | Pershing Square Signature Center, 480 W. 42nd St. | Through Sep. 10: Tue.-Thu. at 7:30 p.m.; Fri.-Sat. at 8 p.m.; Sat.-Sun. at 2 p.m. | $40-$140 at ticketcentral.com or 212-279-4200 | One hr., 40 mins., with intermission

CURVY WIDOW | Westside Theatre, 407 W. 43rd St. | Mon., Wed., Fri.-Sat. at 8 p.m.; Tue. at 7 p.m.; Wed., Sat. at 2 p.m.; Sun at 3 p.m. | $79-$99 at telecharge.com or 212-239-6200 | One hr., 25 mins., no intermission