BY LESLEY SUSSMAN | A two-and-a-quarter-mile section of the East River waterfront from E. 14th St. to E. 23rd St. will, possibly within two years, have a variety of new features that would provide protection from future hurricanes while also allowing the community easier access to the park. The project would include such new amenities as a scenic bike path, a cafe, small retail shops and even an elevated park.

At least this was the prediction of city officials and a representative of the design firm in charge of the storm-surge protection project who appeared May 19 at Washington Irving High School to update Stuyvesant Town and Peter Cooper residents on what’s in store for their section of the waterfront.

In addition to a large turnout of local residents and Community Board 6 members, the workshop was also attended by officials from the Mayor’s Office of Recovery and Resiliency, the city’s Department of Design and Construction, the Department of Transportation and the Parks Department — agencies that are all co-sponsors of the plan.

It was the first of three workshops scheduled for this month to discuss ways to reduce risks from extreme weather and climate change. Local residents are being asked for their input into what the final version for the East Side Coastal Resiliency Plan — being funded by a $335 million U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development grant — should look like.

The second workshop, on May 20, focused on the resiliency plan in the section between Houston and Montgomery Sts.

The third workshop, on Thurs., May 28, at St. Brigid’s Church, 119 Avenue B, will focus on the section between E. Houston and 14th Sts. Doors open at 6:30 p.m.; meeting starts at 7 p.m.

The finalized resiliency project calls for the construction of the “Big U,” a 10-mile-long protective barrier system to be built along the East Side from E. 42nd St. down to the Battery and then up the West Side to 57th St.

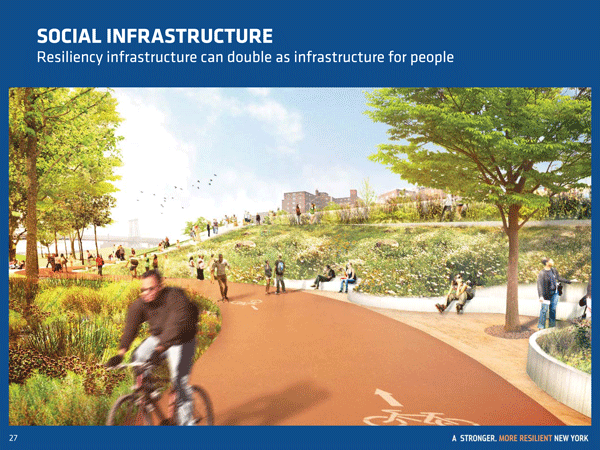

At the May 19 meeting, Jeremy Siegel, a representative of the Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG), the Danish design firm in charge of the project, said ideas that his firm are considering include a series of rolling hills and bridges between the east side of the F.D.R. Drive and the river, a new landscaped berm between 10 feet to 20 feet high depending on the location, levees, collapsible flood barriers, an elevated park on top of a levee, a kayaking area, cafes, small retail shops and a bike path

Siegel emphasized that the most important challenge his firm faced was to protect Lower Manhattan from storm surges, yet without walling the waterfront off from the city. Part of the project, he added, was to devise ways to fix areas that were heavily damaged by Superstorm Sandy in 2012.

Other ideas floated by Siegel included a “wiggle wall” flood barrier that would also be a “piece of art” — basically, flood-barrier panels that could be stored until extreme weather hits — and a basketball court.

In general, he said, the concept design at this point calls for rolling hills that complement the park, yet are tall enough to keep the river from spilling over during a storm.

“It’s all really a juggling act,” Siegel said. “We’re trying to protect the city from storm events. but we want the other 365 days of each year to have the best urban design, and not create a visibility issue with the river. But we want to get a lot more community feedback before we finalize the design plans.”

Siegel said this particular section of the waterfront — between E. 14th and E. 23rd Sts. — posed many design challenges because of the presence of the Con Ed plant with a more than 100-year-old infrastructure, Stuyvesant Cove Park, Asser Levy Playground, the Veterans Affairs Hospital and the F.D.R. Drive viaduct.

He also noted that not every stretch of the waterfront had the width to accommodate a full berm, particularly around the Con Ed plant. As a result, Siegel said, at some locations a simpler floodwall would be built, while at others, a deployable surge barrier would be installed. However, he said, a berm offered the most effective protection.

Another challenge, he added, was how to create storm-protection barriers without creating “a visibility issue.”

“We also want to see how existing trees might be impacted by the new landscape,” Siegel said.

Siegel also reported that his firm had finished 95 percent of the land survey for the overall project, as well as 70 percent of the inspection of bridges from 42nd St. to Battery Park. He said that an underwater structural survey by divers of most of the waterfront had also been completed.

Elise Baudon, a planner with Starr Whitehouse Landscape Architects and Planners, a firm on the project’s urban design team, reported that three workshops held last March on design plans for this strip of the waterfront were attended by more than 135 local residents.

“The majority of residents who attended wanted a nature walk and a cafe in Stuyvesant Cove Park,” she said. “They also said that 20th St. was the major access point to the river and were concerned about safety for pedestrians and bicyclists who crossed there to get to the park.”

Starr Whitehouse was an original member of the “Big U” team that won the hundreds of millions in federal funding for the project.

Carrie Grassi, from the city’s Office of Recovery and Resiliency, told workshop attendees that the agency has “a very ambitious timetable.”

“We want ground to be broken by 2017,” she said.

“The city is committed to this project and is prioritizing it,” she said. “Community input is crucial to this process and that’s why we’re going to have two more sets of workshops sometime in July.”

Grassi said that the city was also working closely with Community Boards 3 and 6, which recently formed a Waterfront Resiliency Task Force, and with other interested parties, as well in smaller focus groups.

C.B. 6 Chairperson Sandro Sherrod is the task force’s chairperson.

“I’m eager to hear more about how some of the berms and other structures that might block views and might block access to the park will be incorporated into the final design plan,” he said.