BY JIM MELLOAN | Soon after my family moved from New Jersey to London in the fall of 1966, we started paying a lot of attention to the music, largely through “Top of the Pops,” the half-hour Top 20 countdown TV show that came on the BBC every Thursday at 7:35 p.m. We got to know acts pretty much unknown on the other side of the pond: Dave Dee, Dozy, Beaky, Mick & Tich; Val Doonican; Des O’Connor. We endured seven weeks of Tom Jones’ “Green, Green Grass Of Home” at No. 1 (my mom purchased a copy). But it was a little while before we heard from the Beatles. They had released the “Revolver” album and their most recent single, “Eleanor Rigby”/“Yellow Submarine,” in August of 1966. They broke their silence in mid-February of 1967 with the release of another double-A-sided single: “Penny Lane” and “Strawberry Fields,” and in doing so ushered world culture into an entirely new era. It was the beginning of the late ’60s, the time span of just three or four years that most people think of when they think of the ’60s.

It was soon clear that the single was a must-have for our household, and Mom bought a copy. The cheery melody, brass section, and nostalgic lyrics of “Penny Lane” were right up Mom’s alley, of a piece with Paul’s later-released songs “When I’m Sixty-Four” and “Your Mother Should Know” — what John used to call his “granny songs.” “Strawberry Fields” was also a nostalgic song about Liverpool, but of a completely different sort. “Let me take you down,” John proposed, to a place where “nothing is real.” I don’t think we knew this song when we got the disc. It was much darker, stranger. The recording of John’s voice sounded so weird that it caused my dad to wonder if there might be something wrong with our record player.

The group had just begun work on what would become the “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band” album, and the two songs were originally meant to be included on it. But Brian Epstein wanted a new single, and George Martin decided to give him those two, which he thought their best work yet. He later expressed regret that they weren’t part of the album. Both songs featured a multitude of instruments and orchestration that surpassed anything the Beatles had put out thus far.

Along with the single they released a pair of promotional films, which aired on “Top of the Pops” on February 16. It was everyone’s first glimpse of the Beatles with — gasp! — facial hair. The films are one of the first examples of what came to be known as music videos.

Strawberry Field was name of a Salvation Army children’s home near John’s childhood home. He and his friends used to climb over a wall to play in the garden next to the building. John’s Aunt Mimi used to warn him not to play there, and he would respond “They won’t hang me for it.” “Nothing to get hung about” means literally that — nothing to do with so-called “hang-ups,” which at the time was really an American expression. The lyrics explore the age-old condition of difficulty in relating to others, and yet “it all works out. It doesn’t matter much to me.” In a perfect rendition of semi-coherent stoned rambling, expressing the vital urge to make oneself understood and blowing it completely, John sings, “Always, no, sometimes think it’s me. But you know I know and it’s a dream. I think, er, no, I mean, er, yes, but it’s all wrong. That is I think I disagree.”

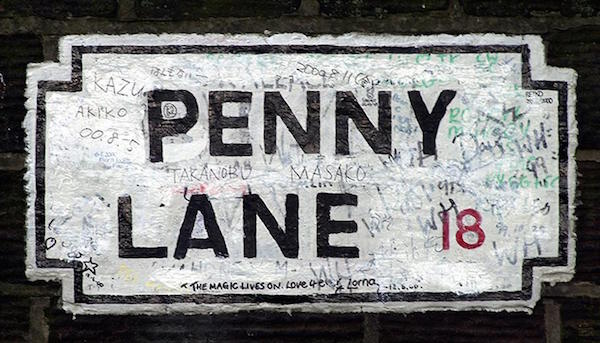

When John brought the song to the band, Paul took up the challenge. He would write his own Liverpool nostalgia song as a counterpoint, and his would be bright and sunny. Penny Lane is the name of one of the Liverpool streets that came together at a busy bus terminus that went by the same name; the song is about the roundabout there. Paul and John would have to change buses at the terminus when they went to visit each other.

Paul sketches an idyllic tableau, with the banker with a motorcar, the fireman with an hourglass and a portrait of the queen, the nurse selling poppies from a tray, the barber showing photographs of every head he’s had the pleasure to know. For a long time, re: the banker, I thought the line was “the little children have an M behind his back,” and I wondered what that meant. The slyest lyric is “a four of fish and finger pies,” a kind of chain pun in which “four of fish” means fourpence worth of fish, “fish and finger” alludes to fish fingers, and “finger pies” is Liverpool slang for the very intimate kind of fondling that might go on with couples in the bus shelter. Paul called it “a nice little joke for the Liverpool lads who like a bit of smut.”

At the American School in London we got to go to nearby Regent’s Park on our lunch breaks during that magical Spring, and as a budding song parodist with such gems as “Stranglers in the Night” and “Meet the Stinker, Polaroid Stinker” under my belt, I found common ground with my friend Dick Wilson, who would sing, “Cellophane is in my ears and in my eyes.”

It was the colorful, cheerful heart of the Swinging London era. In the US, it would soon be the Summer of Love. The single was kept out of the No. 1 spot in the UK by Engelbert Humperdinck’s “Please Release Me.” Here in the US, “Penny Lane” was at the top spot just for the week of March 18, 1967 — 50 years ago this week.