BY GERALD BUSBY | Most of the creative people I know are gay snobs. They range from narcissistic bodybuilders and clerks at Bergdorf Goodman to international fashion models and performers at Carnegie Hall. Gay snobbery, like all other kinds, is an expression of the ego, but it takes on a special quality when used as a defense against assaults based on sexual identity. It’s also an effective way to get attention; it’s a character gay men create to display their most extravagant, and most sophisticated behavior, practical and artistic.

“I never felt like I fit in anywhere in the gay world, so I wanted to be a snob,” Garrett Swann told me. “Gay men seem to form cliques, and I felt excluded. I was always attracted to affluent men, and I always felt I was asking their permission to exist, to know what to do, and how to do it.”

Ah, the allure of existential dependency — the luxury of being told what to do by an older, richer, more sophisticated man. “I thought being a snob would give me a sense of security, but it didn’t,” Garrett recalled. “Being a snob is being first and foremost competitive; being prettier, being more in shape, having fancier possessions, flying first class on Lufthansa.”

Young gay men want models to define their sexuality — and ego, principally in the form of narcissism, plays a central role in that yearning. Garrett continued, “I met an older affluent man on a nude beach at St. Bart’s in the Caribbean, and he flew me to Atlanta every five weeks to socialize with him and his rich gay friends. There was a hierarchy of prestige among them, and they divided into cliques with specific tastes for exotic food, sex, and drugs. I thought I had arrived, though he called me a brat for wanting things and never being satisfied with what I had. He disdained my lack of confidence in being who I was at the moment — being with him.”

Garrett confided that in those halcyon days as the darling of a rich older man, he confused snobbery with confidence. In his 30s, living in Los Angeles, he easily found his way into elite social groups, especially one where a wealthy fag hag, an heiress to the Pepsi fortune, ruled the roost and paid for lavish parties populated by pretty young gay men. She too, like the man in Atlanta who spent Christmas at St. Barts, spoiled Garrett with gifts and hedonistic delights. “Not being from a family of money, I always felt like an outsider. I was the court jester who kept everyone laughing. I really felt I had arrived when I got a role on a [2006] Fox TV series with Bo Derek and Tippi Hedren called ‘Fashion House.’ I would get drunk and call my friends to tell them how famous I was going to be. That was the peak of my narcissism. Ego reigned.”

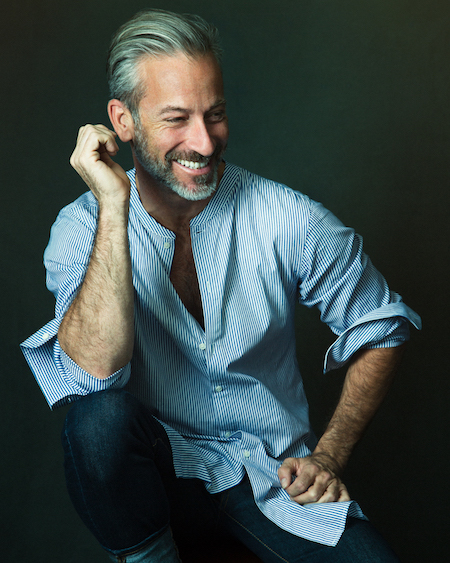

Garrett found his way out of that quagmire when he quit alcohol and drugs, and went on to a successful career as a fashion model. OUT Magazine recently featured him in an article titled: “DILF: These Nine Gay Men Prove That Aging is Sexy.” Garrett is 48. He’s currently creating a business that capitalizes on all the lives he’s lived, all the places he’s gone, and all the gay snobs he’s fallen in love with. Garrett Swann’s snobbery took him down some rocky paths and also taught him who he is.

Then there’s Craig Rutenberg, a person who deserves to be a snob more than anyone I ever knew. He personifies sophistication, and he’s a masterful musician. When we met in 1972, he was 19 and was with the distinguished composer and critic, Virgil Thomson at a dinner I cooked in a friend’s apartment in the West Village. Craig was a bright and attractive young gay man whose unwavering alertness conveyed that he knew what he wanted from life and how to get it. Here he was, a teenager, holding his own in conversation with Virgil Thomson, an international celebrity who wrote and produced “Four Saints In Three Acts,” an opera with an all-African American cast, and a libretto by Gertrude Stein. Craig spoke knowledgeably about the food I had prepared, and we became friends and food snobs. We still are after 45 years.

It’s important to distinguish between the contexts of snobbery — opera, food, wine, literature, painting, movies, place settings at a dinner party — and the sheer physicality of affectation. Craig’s consummate musicianship and expertise as an opera coach and accompanist for the best singers in the world put him in a unique category of superior behavior. Yet as a gay man who is overweight, he has been a target of ridicule and disparaging comments for much of his life. A few years ago, Craig accompanied the Canadian tenor Ben Heppner in a recital at the Berlin Philharmonie. One critic commented on their heftiness as they strode sturdily on stage to begin the program. It was a bit nasty, though measured with praise for their artistry.

When Craig was 15, he went to Germany and was introduced to a classical European education by Friedelind Wagner, granddaughter of the composer, Richard Wagner. Craig took to it voraciously. Friedelind had a production of “Lohengrin,” one of her grandfather’s most popular operas, and she took Craig to meet the singers and production crew. She also took him to Leipzig, Dresden, and Bayreuth, where he met many famous people. Craig told me it was his “first glimpse of what real theater and real music-making could be.” It’s no wonder that he developed a personality that connected him with elite society. His snobbery was born with provenance.

Back home in New Haven, Craig accompanied choirs and singers at their private lessons. Craig’s Great Uncle Fritzi Kniehl, who was his first piano teacher and a major influence, told him that opera companies hired pianists to accompany rehearsals and prepare singers to perform with the orchestra. Craig knew instantly that was for him.

As an undergraduate at George Washington University, Craig majored in German and Italian, the two most prominent languages in opera repertoire, and he began to study seriously the operas of Wagner, Verdi, and Puccini. With Friedelind, he had watched famous singers being coached in their operatic roles, and that had excited him. So he took jobs accompanying singers at the Washington Opera Society, and felt comfortable doing so. Attitude is something else he felt comfortable doing.

There’s an imperiousness that big-time singing teachers have which marks their unequivocal authority to say things to their students like, “Life your Instrument!” Their attitude is often clearer than their words. When Craig began prompting singers at the Houston Grand Opera, this was an important tool in his learning the scores comprehensively, by following precisely every note and word the singers were singing in English, German, Italian, or French. In the prompter’s box at the center of the stage and level with the floor, Craig silently performed with the singers, and could quickly rescue them if their concentration failed. Craig learned pacing in the prompter’s box — exactly how slow or fast a phrase should move to be practically executed by the singers and clearly perceived by the audience.

Snobbery is implicit in such extraordinary skills, and I think anyone who understands exactly what Craig Rutenberg does would agree.