By David Todd

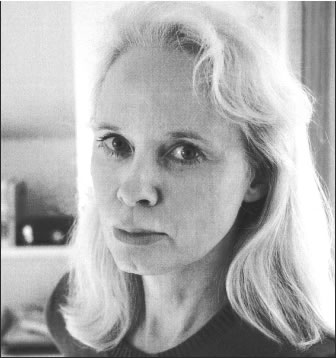

A behind-the-book interview with New York author Mary Gaitskill

The fiction of Mary Gaitskill—currently on sublime display in her third collection of short stories, “Don’t Cry”—is not safe for dysmorphics or Iraq war veterans or any other potentially vulnerable types, by which I mean everyone.

Since her debut anthology “Bad Behavior” in 1988, Gaitskill has been known for her brutal honesty (“Dolores did not look good in a scarf. Her face was fleshy, her nose had a bulby tip,” this new volume begins), but she should never be dismissed as a bitter antagonist. She’s simply too observant, her pain too connected to the dispatches she is forever picking up on her emotional-intelligence radio. In stories like “Today I’m Yours” she explores the half-hearted obsession of an ongoing side relationship; in “Mirror Ball,” she tracks the soul of an “elfin girl” as it’s taken by a San Francisco musician. A National Book Award finalist for 2005’s “Veronica” (her second novel after 1991’s “Two Girls, Fat and Thin”), Gaitskill doesn’t capture the zeitgeist per se with these selections, nor does she deliver the perfect urban-contemporary tableau. Instead, Gaitskill offers something vital that doesn’t fit into any particular package: the voice of the smart loner conveying the inner lives of the often not-as-smart outsiders she’s drawn to.

David Todd: You’ve been putting out a collection of stories every ten years or so. Do you see your goals as a writer changing from one to the next?

Mary Gaitskill: I don’t think one sees oneself as a “writer,” one just is writing, doing what you’re doing. Goals as a writer do evolve, but I don’t think one is usually conscious of it like that. It’s just something that happens naturally.

DT: It seems like you’re doing some different things with this new collection.

MG: Well, I’m glad that they’re showing a development, definitely.

DT: A story like “Folk Song” appears more meta-fictional than your previous work.

MG: Oh, that’s certainly different in terms of the form of it. That was almost like a playful thing. I went though a period after [her second collection, 1997’s] “Because They Wanted To” where I didn’t write much in the way of fiction. I was having trouble making money; I was really scrambling. I think I was going through a period of internal change; it was like there was a tectonic shift going on and I couldn’t get my feet on solid ground enough to really create.

At that time Nerve.com asked if I would write something for $2,000 and said they had to have it quickly, and so I wrote that almost as an experiment. And I wrote it much more quickly than I usually write; it’s short, but I think it only took me five days, which for me is a record. And I did it on purpose, sort of because I wanted to break out of my old way of doing things, like struggling so hard over every line. But I liked it. There are other stories like that which did not get into the collection, but “Folk Song” I liked. So that’s the answer to that one in terms of style.

DT: There’s a meta-aspect to “Description,” too.

MG: You mean, the kinds of things that they talk about in terms of writing?

DT: Yes. The two main characters—both young men, recent MFA grads—argue over the value of descriptive writing.

MG: Well yeah, I was talking about it explicitly in the story; I put a lot of my ideas in the mouth of one of the characters. But I think that that’s a bigger issue than concerns merely writers. For me it’s about observation of the world, about the mystery of the world. And that’s really what the boys are arguing about in some ways. The one of them, Joseph, he sees the physical world as a place of softness and wonder in a sense that the other boy, [Kevin,] doesn’t, not because he’s dumb in any way but…he isn’t attuned that way. And to Joseph he’s just missing so much, and yet at the end, Joseph thinks Kevin will always win. That’s just the way it is. Whereas to me, the way Joseph’s sitting there, looking out, he’s always going to see things that Kevin will never see.

DT: “Don’t Cry” presents the kind of internal life your stories are known for, but also more of an external conflict for the two women on an adoption trip to Ethiopia.

MG: To me, what’s unusual about that is that it’s much more plot-driven than most of my stories. In fact, I made a conscious effort to scale back the internal life because it was a very complicated plot that had to move forward. And so I was more spare than I might normally be in my treatment of observation and the inner world. Although, Janice is dealing with a really profound inner-world transformation; she’s dealing with grief, so that was very important as well. It was almost [like] part of the dynamism of the story had to do with rubbing together the inner world and outer and [seeing] how they met in some dramatic way.

What I found the most challenging about that story was that it had a number of dramatic peaks. Usually you reach one dramatic peak and then you come down from it; in this one, I think there’s at least three of them. And I found it really hard to get the timing of that right. I’m not sure I could explain exactly how I did it, but I was aware of that as a challenge.

DT: The flash-forward scene seemed well-placed, near the end.

MG: Thanks. Because I wondered where to put that, I almost put it right at the end. It didn’t seem to work there.

DT: As a reader of your work, I’ve always wondered how you see yourself as fitting into the literary world. Do you feel like you have a niche in it, or are you on your own?

MG: I do kind of feel on my own. If people are still paying attention to books 50 years from now, probably somebody could put me in some group or other, but as of now, I don’t.

DT: Does that make you uneasy?

MG: It does. Or not uneasy exactly but…I just every now and then feel like the cheese that stands alone.

DT: The what?

MG: The cheese that stands alone. [From “The Farmer in the Dell.”] (Laughs.) But I’m sure a lot of writers feel that way. Because being a writer, you are very alone most of the time, even if you do see yourself as part of a group.

DT: Early in your career, it seems like you could’ve been placed in a kind of urban hipster category.

MG: Yeah, well when it first came out like that, I was surprised, but pleasantly. I thought, oh, if people want to see me as a hipster, that’s good. They can do that. (Laughs.)

DT: Did that turn for you at some point, or did you have to let that go?

MG: Well, it wasn’t totally irrelevant; I mean, if I had a milieu at all, it was the type of bohemia that was happening at that time. But [that image] affected me, it was kind of an identity that I could take on, but it didn’t feel like deeply a part of me. I remember there was some book that came out in the ‘90s called “Shopping in Space.” It was these two British people who were interviewing American [writers]— Lynne Tillman was in there, and I was, Bret Ellis, Tama Janowitz. But they didn’t like me. They thought I was really not a hipster after all, that I was really more like a New Yorker writer, and in their mind that was a term of disapproval. And I remember thinking at the time, I was like really, I’m a New Yorker writer? Where’s the money? (Laughs.) In a way, I was happy to be disavowed by them, because I thought, well good, I don’t have to worry about fitting into this category anymore.

DT: Now you’ve been published in the New Yorker a number of times.

MG: Three times, I think.

DT: Not to disparage that, but are you any more comfortable in that world?

MG: I don’t go to the parties. I don’t get invited to the parties most of the time. Um…No, I wouldn’t say that I am.