BY LINCOLN ANDERSON |

How does it feeeel?

How does it feeeel?

To be on your own

Like a rolling stone

Like the 2016 Nobel Prize

winner for literature?

Of course, that last line wasn’t actually in Bob Dylan’s ’60s anthem “Like a Rolling Stone.” But, yeah, it must feel pretty good! … Or so one would think.

But after winning the world’s most prestigious literary award last Thursday, Bob Dylan so far has remained silent about it. He hasn’t said a word on it publicly. He hasn’t responded personally to the Swedish Academy. He’s currently on an American tour, but hasn’t uttered a peep about it while on stage, either.

It’s not even known if Dylan will accept the award at the Nobel ceremony on Dec. 10 — or decline it, like Jean-Paul Sartre in 1964. At this point, you could say, “The answer is blowin’ in the wind.”

But the musician’s fans note it’s just par for the course for the always-unpredictable artist.

In interviews with The Villager, musicians who knew and played with Dylan during his early formative years in Greenwich Village in the 1960s, and others who have followed his career closely, said they feel great for him — and that he absolutely is deserving of the honor.

The Nobel Prize in literature was awarded to Dylan “for having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition.”

Some writers, though, were quick to slam the choice of a popular-music star. It was, in fact, the first time in the award’s 115-year history that it was bestowed on a singer-songwriter.

Scottish novelist Irvine Welsh, the author of “Trainspotting,” for one, in a blistering critique, said, “I’m a Dylan fan, but this is an ill-conceived nostalgia award wrenched from the rancid prostates of senile, gibbering hippies.”

But Dylan fans hailed the choice.

“I think it makes a lot of sense that he received the award,” said Richard Barone, the lead singer of the Bongos, a new wave band that made a splash on the New York scene in the 1980s.

“He’s the most deserving of his generation, he’s the most literate,” he said of Dylan and his peers.

Barone, who still tours and also teaches performance at New York University, has lived in the Village since 1984. He said that, in his view, it was the historic neighborhood that helped make Dylan who he was, and really informed his songwriting.

“I think, particularly, why he won that prize is because he lived in the Village,” he said. “In all of his early songs, I really feel the Village itself — the landscape, the architecture, the immigrants. He didn’t write in a normal 1960s way. He wrote like it was 100 years earlier. He wouldn’t have written that way if he lived in Miami. Dylan was so experimental with his songs — it was all about the words.”

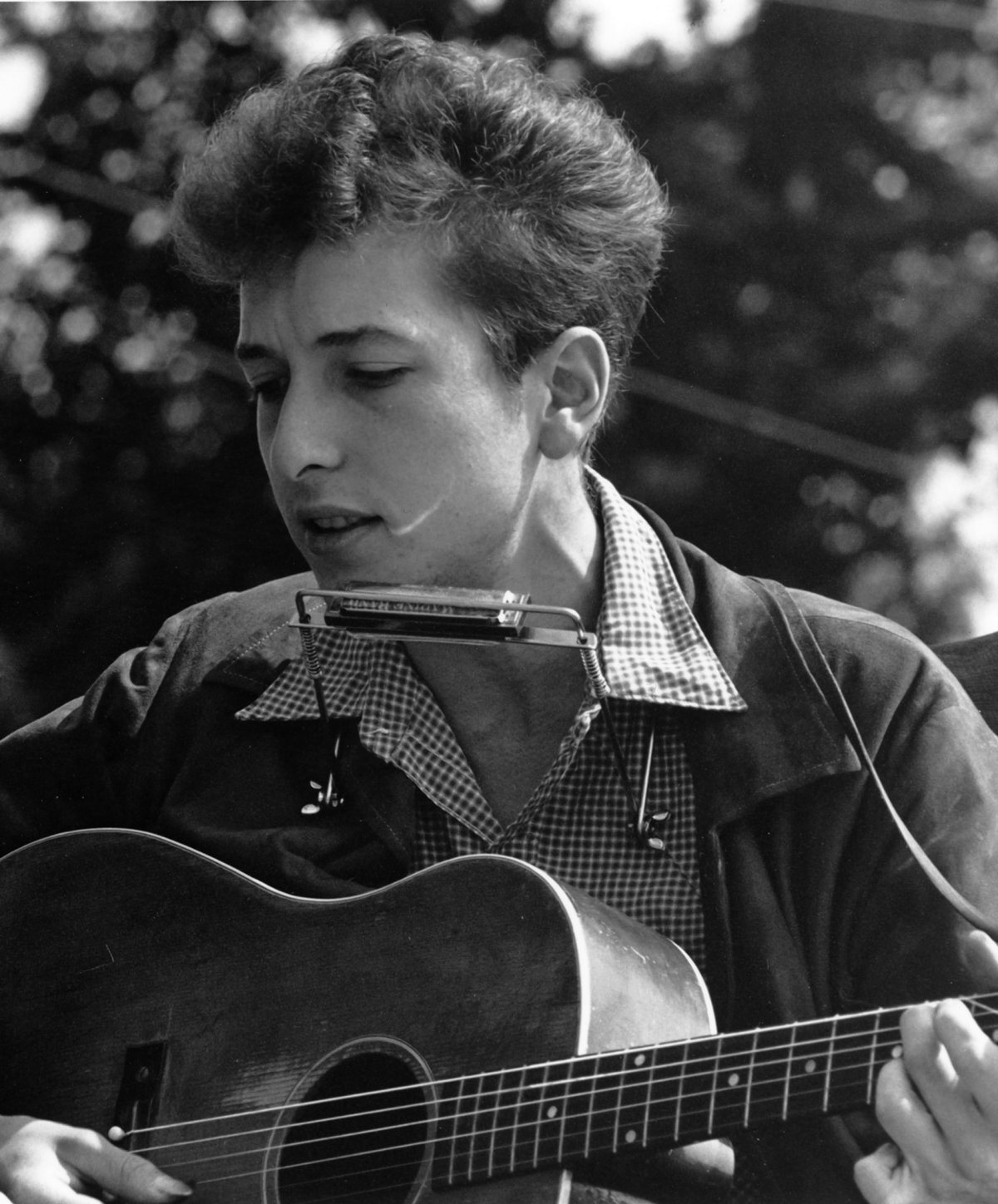

Dylan grew up in Minnesota. But there was only one place to be if you wanted to make your mark as a folk singer back then — Greenwich Village, with its burgeoning folk scene — and so that’s where he came in 1961.

Dylan lived in the Village, with about a five-year hiatus in Woodstock, through the early 1970s, before moving to California.

The folkies immediately knew they had something unique in Dylan when he landed in the city.

“I met him when he first came to New York,” said Happy Traum, who with his group, The New World Singers, recorded the first version of Dylan’s “Blowin’ in the Wind.”

Dylan had given the song to Gil Turner, Traum’s fellow band member and emcee of the legendary Gerde’s Folk City, at W. Fourth and Mercer Sts.

A few months after Traum’s band recorded the famed ballad, Dylan would release his album “The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan.”

“There was already this incredible buzz around the Village about him,” Traum remembered. “We all thought he was in itinerant carnival performer who hopped freight trains from New Mexico — that was the original story.”

Beyond his Woody Guthrie-inspired tall tales that proved to be just that, right away Dylan was clearly different. He made the others seem, well, vanilla.

“We all sang these songs,” Traum said, “but his phrasing or the way he would subtly change the melodies around — it was totally engaging. Then when he started to write songs, it was totally mind-blowing.

“We knew he was special. He was the topic of everyone’s conversation right from the beginning.”

Dylan was very approachable and humorous back then, with an “impish charm,” he said.

The traditional folk scene started out humbly, recalled Traum, who grew up in the Bronx and had been at it since the mid-’50s. The musicians were, for the most part, just playing for joy of it, not expecting to make careers out of it.

“There were little ‘basket houses’ in the Village where you’d do a set and hope you’d get some money,” he recalled. “It was a very small scene.”

But then Peter, Paul and Mary had a huge international hit with, again, Dylan’s “Blowin’ in the Wind” — just a few months after the song was released on Dylan’s “Freewheelin’ ” — and folk music took off.

“By the time Dylan came along, the scene was bubbling, and he took it to another level,” Traum said. “Right away, ‘Blowin’ in the Wind’ was a masterpiece of lyric writing. Nobody had ever written a song like that before.”

Traum recalled one night at Gerde’s after last call when Dylan debuted “A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall” for a few musicians who were hanging around.

“We heard that song and it was just jaw-dropping,” Traum said. “It was so powerful. There were the Everly Brothers and Elvis — but this was on another level. Other people were writing songs. You had Phil Ochs and Tom Paxton, but nothing of the scope and depth of Dylan’s songs. He was extraordinary.”

Dylan’s guitar playing was unique, too, he said, as he would use it to accent his lyrics just a little bit differently than others would.

However, Traum admitted, “Back then, we would never have thought he would win the Nobel Prize for literature. But now, you look back, 50 or 60 years later, and you say, ‘Yeah.’ He just kept putting stuff out. He never stopped.”

Traum recalled visiting Dylan and his then-girlfriend Suze Rotolo for dinner when the singer lived in a walk-up apartment on W. Fourth St., where Dylan resided for two or three years.

“He made steaks, as I remember,” he said.

In 1965, Dylan moved to Woodstock, where he reportedly had a motorcycle accident in 1966.

“He had fractured a vertebra in his neck,” Traum said. “It made him realize he had to slow down, stay around home a bit more.”

Traum also moved to Woodstock, though for good, in ’66, and would visit Dylan up there, too. He said he remembered seeing a typewriter in Dylan’s Upstate home, but isn’t certain if he saw one at his W. Fourth St. pad. He’s pretty sure, though, that Dylan typed his lyrics.

“He spent quite a lot of time on them,” he said. “He used to spend quite a lot of time at his typewriter.

“I think ‘Blowin’ in the Wind’ he gave us on a typewritten piece of paper,” Traum recalled of when Dylan handed The New World Singers the lyric sheet.

Dylan clearly had a literary bent, he said, noting, “He always had books around. He had a lot of bookshelves. He read a lot of different kind of things. I know he read a lot of poetry. He was into reading the Bible for a while, and the classics.”

Eric Andersen, another singer-songwriter, met Dylan in the Village a few years after he had burst onto the scene.

In an e-mail from Norway, where he now lives, Andersen wrote, “I was introduced to Bob through Phil Ochs in the winter of ’64. I came to the Village as a songwriting newcomer from Buffalo. Dylan would sometimes try out new songs at the hoots at the Gaslight. I heard him perform ‘The Hour When The Ship Comes In’ there one winter’s eve. Or we would whisper lyrics to each other in the Kettle of Fish.

“Late one night when Bob got off the road from New Orleans, he and Victor, his road manager, parked their blue Ford station wagon on Bleecker St. and we went up to Phil Ochs’s. Bob whipped out a guitar sang a brand-new song called ‘Hey, Mr. Tambourine Man’ over Phil’s coffee table. Later, when pressures mounted for me to be drafted into the Vietnam War, Bob became one of my two draft counselors. I got out of it. We became friends.”

As for Dylan’s winning the Nobel for literature, Andersen said he merits it for his powerful lyrics.

“I believe it’s true that a great lyricist/poet can be as deserving of that prize as any great prose writer or blank-verse poet,” he said. “Shakespeare might have won it for his sonnets alone. I commented on Facebook in response to Dylan’s winning the Nobel, ‘Heartfelt congrats to our dearest poet Bob who brandished a big blade of light to cut through the jungles of our darkness. Bob took the power of the word into the future.’ ”

David Amram was another contemporary of Dylan’s back in the 1960s and ’70s, though he wasn’t a folk musician per se.

“That’s quite some news,” he said of Dylan’s snagging the esteemed award. “It’s nice for all of us to see someone get an award that opens up the door for other poets and musicians and singer-songwriters.”

Amram, who is about to celebrate his 86th birthday, used to gig around at various types of venues in the Village. A classically trained eclectic musician, he would jam with jazz great Dizzy Gillespie at the Village Gate, then go sit in and play in the background with the folk musicians at the Kettle of Fish.

The Village’s tight-knit scene helped Dylan and other musicians grow and hone their craft, he said.

“Everything was smaller and there was much more of a communal sense,” Amram recalled. “Everyone benefitted, including Dylan, who was a scholar of music.”

Asked if he hung around with Dylan, Amram vividly recalled one project involving famed Beat poet Allen Ginsberg that they both worked on.

“We spent a whole pretty much part of a summer together in 1969,” he recalled. “We collaborated on a recording with Allen Ginsberg. Allen decided he was going to be a singer-songwriter — and he started out at the top!”

So Ginsberg sang on the album?

“So to speak, yes,” Amram said. As for Dylan, he said, “He was being a good sport and playing the guitar.” Amram played French horn and worked on the compositions. Happy Traum was involved, too.

Amram lived in the Village for 40 years, but now calls Beacon, N.Y., home. He said he always had a lot of respect for Dylan, and that giving him the Nobel is a great thing for art, in general.

“I always enjoyed him,” he said of Dylan. “He had a wonderful personal way of doing stuff. He was really honest. He really cared. He was very private, and I respected that.

“Anything that takes the idea of art out of the ivory tower is good,” Amram said. “The Nobel committee did that.”

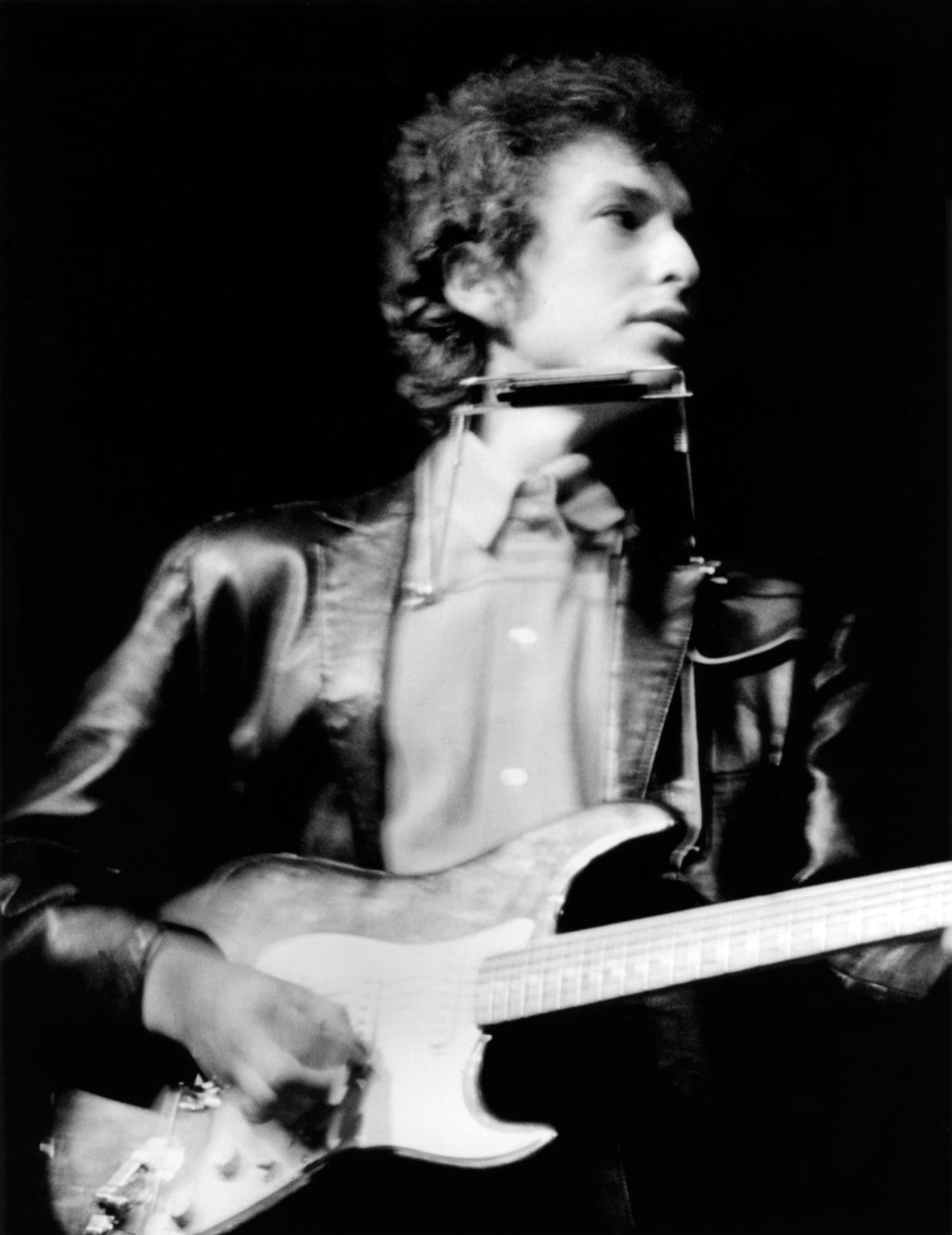

Bob Gruen, the renowned rock-’n’-roll photographer, came to the Village in 1965. He covered the Newport Folk Festival that year where Dylan famously “went electric” and set off a firestorm of debate in the folk community. Gruen, who was just starting out as a shutterbug, managed to get himself right up in the front row at the historic event.

“It was my first photo pass,” he recalled. “I kind of bluffed my way in. I wasn’t shooting for anyone yet.

“Dylan was the headliner. He played electric. People weren’t just booing — some were cheering. It was very chaotic. What he was doing was basically announcing that rock ’n’ roll was the folk music of America — and I think he was right.”

Dylan’s lyrics had a profound effect on him as a youth, he said.

“When I was growing up, Bob Dylan was kind of like a Bible to me,” Gruen said. “I learned about spirituality from him, sociology, psychology. When I was a troubled teenager and I felt my mother didn’t understand me, I played Bob Dylan’s ‘It’s Alright Ma’ for her.”

Asked if she “got” the lyrics’ message, he said, “No, not really.”

But that didn’t diminish the evocative power of the singer’s words for him.

“Bob Dylan’s lyrics are very visual,” he said, “and for me, as a photographer, that’s important. Every time I hear a Dylan song, I think of different images, depending on what I’m thinking of at the time, and it’s always fresh, and that’s why I like it.

“When I first heard him, I didn’t think he was much of a singer,” he admitted. “But the rhythm and the cadence and what he was saying — later, I realized was very emotional and powerful the way he does it. He wasn’t singing ‘Moon in June’ simple love songs that rhyme.”

As to whether Dylan deserves the Nobel for literature, Gruen said, “Sure. I think he’s the conscience of many people around the world.”

He noted that it took a while for Dylan to catch on in places like Japan, for example, due to his lyrics-heavy songs.

“But I saw him playing in ’94 at the Budokan and people were loving it,” he said.

In the history of the award, 11 poets have won the Nobel for literature, among them Rudyard Kipling, William Butler Yeats, T.S. Eliot, Pablo Neruda, Octavia Paz and Seamus Heaney.

Despite the disdain for Dylan’s Nobel by writers like “Trainspotting” ’s Welsh, one Village author said the bard’s lyrics truly are transcendent, and worthy of inclusion among the ranks of the names above.

“I’m very excited about Dylan winning,” said Susan Shapiro, who teaches writing at The New School. “I’ve adored him since I was 14, and he was an early inspiration for a lot of my creative writing. I think much of his work is pure poetry.”