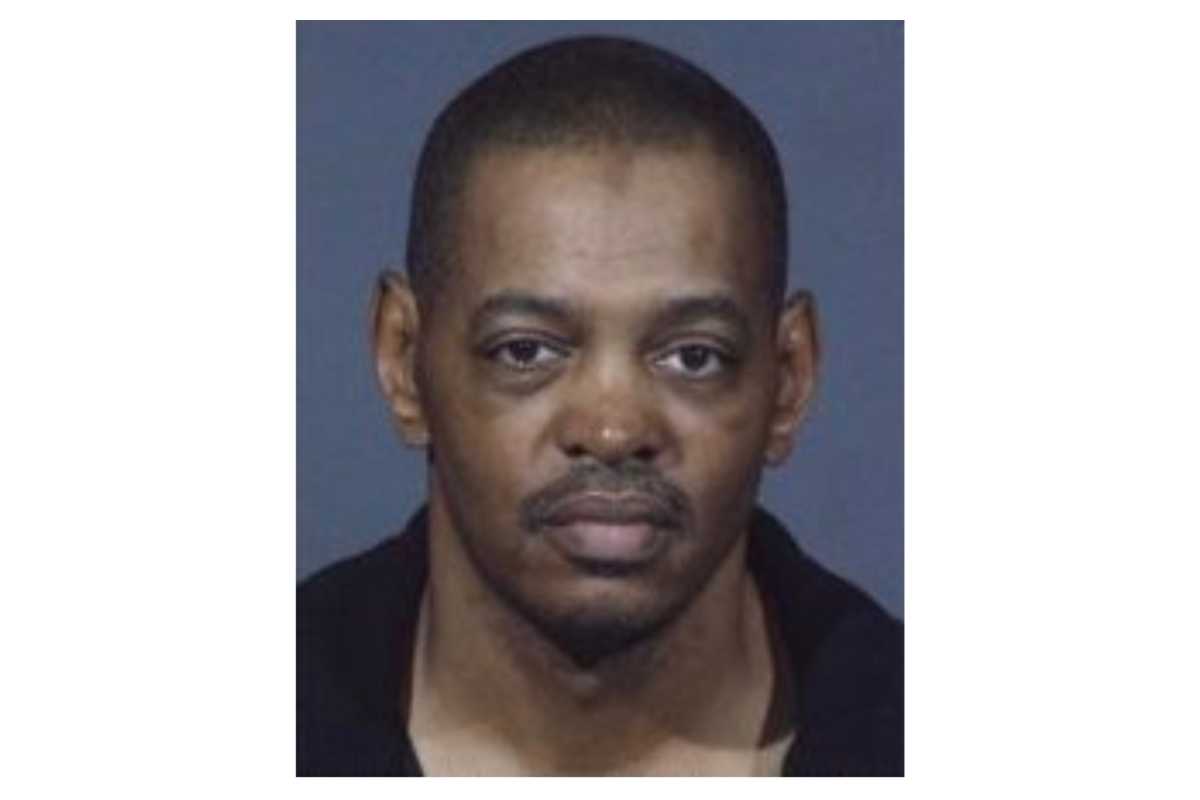

Counting ballots in Nyons, in the South of France, during the recent French presidential election. Photo by Patricia Fieldsteel

BY PATRICIA FIELDSTEEL | NYONS, FRANCE: On May 7, France redeemed itself, not only in the eyes of the world, but also in its own self-image. My compatriots chose to reject a racist, anti-Semitic, xenophobic, reactionary demagogue who tried to seduce the country with her faux empathy for les oubliés (the forgotten ones) — the unemployed, poor and suffering citizens of France.

Still living with the stain of the Pétain years, of collaboration and the government-sanctioned murder of most of its Jews, as well as the horrors of the Algerian War, France voted a resounding No to continuing the shame of that past. Perhaps the specter of the unfolding nightmare in the U.S. also gave the French pause.

Sunday night, I went with my Westie, Emily, to the mairie, or hotel de ville (town hall), for the vote counting, which is done by hand. Voting in France is always on Sunday, with the polls opening at 8 a.m. and closing at 7or 8 p.m. There are two rounds, two weeks apart. Unless one person wins more than 50 percent of the vote, the second presidential round is between the top two candidates. Voting is direct, done by hand, and is by popular vote. Registration is automatic when a citizen turns 18. Women were first allowed to vote on April 29, 1945.

When Emily and I arrived, the counting had just begun. I nodded hello to the two police officers on duty and took a seat between my friend, Ludmilla, who is 92, and the editor of the local equivalent of The Villager. The mood was solemn and respectful. We were not allowed to talk, though whispers were permitted. As is stated by law, the room was divided into five tables with four citizens apiece and a fifth to oversee each table. During the course of the day, voters are randomly asked if they would like to come back in the evening to count. I spotted a number of people I know, including a dog-walking friend who was counting for the first time, as well as the mayor, who was overseeing a table. The scene was the same at Nyons’s four other polling places.

This year, in the second round, two-thirds of those voting had to choose a candidate for whom they didn’t vote in the first round. Nearly one-quarter of all voters abstained altogether. When voters arrive at the polls, they’re given an opaque envelope. Two separate sheets of ballot paper exist, each with the name of a candidate. All paper used has been recycled. The voter enters a curtained booth (“un isoloir”), folds the paper containing his or her candidate’s name and inserts it into the unsealed envelope. Voters exit the booth and drop their envelopes into a clear Lucite box, known as an “urne.” A polling official loudly intones, “A voté!” (“vote cast”), a ceremonial but crucial part of the process. The voter signs the roll and his or her voter registration card is hand-stamped: “A voté.”

Another option exists — casting a “nul” or “blanc” vote, neither of which count. Dating back to the French Revolution, they’re regarded as protest votes. Instead of enclosing a candidate’s name in the envelope, the voter can chose to enclose nothing or a blank piece of paper (un blanc) or to enclose a shredded or otherwise marked-up piece of paper with a non-valid name or message (nul). This year, someone slightly north of here enclosed an unused condom (“un préservatif”) marked “Made in Thailand.” And in nearby Grignan, a town inextricably associated with literature and the great letter writer Madame de Sévigné, voters wrote in “Bob Marley,” “Donald Trump,” “Céline Dion” and “Ni la peste, ni le choléra” (“Neither plague nor cholera”), a play on what many regarded as choosing between the plague and cholera for president. These votes counted as “nuls.”

All nul and blanc envelopes must be examined and signed by an overseeing official, and these votes, despite their not counting, go to the préfecture and eventually the Ministry of the Interior to be examined. Voting nul or blanc is somewhat frowned upon, the feeling being it’s the obligation of every mature and responsible citizen to make a decision.

The counting was an exhilarating experience, witnessing firsthand a representative democracy in action, complete with built-in checks and balances and no room for machine or computer error or fraud. The four people at each table worked in pairs, with one opening and reading out the vote and the other marking it down in the tally; then the roles are reversed.

Throughout the evening, the air was punctuated by staccato cries, “Macron!” “LePen!” “Macron!” “Macron!” “Le Pen!” At 7:16 someone called out, “Fillon!” — the former prime minister — and there were muffled giggles; at 7:30 someone else called out “Mélenchon!” — the far-left candidate — and no one laughed.

When each table finished their tallies, the votes were placed in a larger envelope, sealed, then collected. All ballots eventually go to the Ministry of the Interior in Paris, which oversees elections and spends about €3.84 ($4.20) per voter. The lists are tallied with the number of voters, signatures and envelopes collected. Each precinct is required to submit a report and any irregularities that may have occurred. The mood in the room was somber, strictly nonpartisan but friendly.

This is a small town — a big city around here — of only 7,000 people and everyone knows everyone else or, at best, most everyone in the room knew everyone else “de vue” — by sight.

We waited till the results came in from the four other polling sites and at 8:16 p.m., Socialist Mayor Pierre Combes announced the totals: 2,394 votes were cast for Macron (69.43 percent); 1,054 votes for LePen (30.57 percent); and 488 ballots were nuls or blancs (12.40 percent). Out of 5,440 registered Nyonsais voters, 3,448 made an actual voting choice.

Nationwide, in reality, LePen placed third: 20,254,167 voted for Macron; 11,416,454 voters abstained; 10,584,646 voted LePen. And 4,045,395 chose nul or blanc. In June, the process will be repeated for the national legislative elections, when the real strength of Macron’s ability to push through his agenda will be determined. For now, we are all just breathing a massive sigh of relief.

Fieldsteel, a former resident of Jane St. in the Village, for the past 15 years has lived in Nyons, France.