By Timothy Lavin

In New York City, the center of the dramatic world, developing a theater specifically for children is an idea neither novel nor unique. But the founders of Manhattan Children’s Theater, 380 Broadway in Tribeca, are experimenting with a creative twist: treating their youthful audience members like adults.

When Bruce Merrill and Laura Stevens started the organization in 2002, they hoped to create a new theater company dedicated to high-quality, more serious children’s productions.

“I feel like it’s important to bring back the classics in such a way that makes it accessible to kids and doesn’t dumb it down by any means,” said Stevens, the new theater’s executive director. “Our mission was to make accessible to our audience classical adaptations as well as poignant new work.”

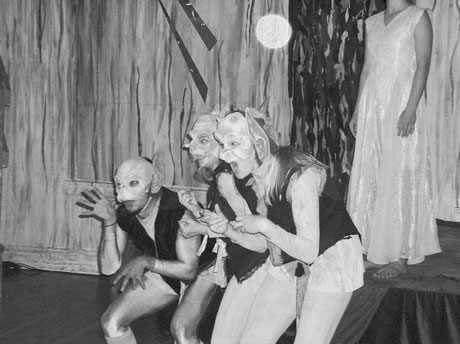

The theater’s latest production is “Goblin Market,” a near-verbatim adaptation of an 1862 poem by Christina Rossetti. In the great tradition of 19th-century children’s tales, it’s actually scary — and suggestively violent. (The show is recommended for children five and over.) Though the goblins, played enthusiastically by Benjamin Oyzon, Jodi Redmond and Marta Reiman, introduce themselves genially to their audience prior to the show, the gruesome masks they later don, designed by Chris Mahle, leave little doubt about the goblin moral disposition.

The story involves two sisters, Laura and Lizzie (Sally Conway and Jannecke Foss), who find themselves beset, “morning and evening,” by beguiling goblin men hoping to sell them fruit of dubious origin. Laura eventually succumbs and lapses into a goblin-fruit stupor, leaving her younger sister to engage and outwit the beasts.

The production, adapted and directed by Merrill, includes ambitious dance sequences choreographed by Harry Mavromichalis and a percussive soundtrack composed by Michael Vitali. The combination, though uncommon in an average Halloween pageant, visibly thrilled the youngsters in the audience last weekend.

“We just want to be able to combine one art form, which is literature, along with other art forms such as theater and dance and music, and be able to incorporate them together into something meaningful,” said Merrill, the theater’s artistic director.

“I think it’s the most sophisticated, challenging piece that we’ve put out there for the kids,” said Stevens. And, she said, it’s been a success. “Kids rise to the occasion. It’s unbelievable.”

After several years working at the Vital Theater Company, a Manhattan group Stevens co-founded, she realized that the market for children’s theater in Manhattan was burgeoning and inadequately served.

“I would see these young kids come in and just really gain a perspective on the world from this art form, and I was like, ‘My God, there’s something here,’” she said. She decided that an independent children’s theater would have a lot of potential in the city.

Merrill, who had been directing Vital’s children’s program on a tight budget at the time, agreed. They formed Manhattan Children’s Theater in May of last year and rented a fourth-floor loft in Tribeca, a space then being used as an art gallery.

“The fact that we could incorporate the company ‘Manhattan Children’s Theater’ in the year 2002 seems sort of funny, I mean how did someone not get that name?” said Stevens. “I think many companies see children’s theater as a means to an end for their adult productions. They take $300, paint some blocks and put black curtains over the adult’s set and throw on children’s theater.”

Several big-time production companies compete for the city’s youth market. But unlike their much larger, more established peers, Manhattan Children’s Theater employs local talent and doesn’t aspire to national touring.

“I haven’t found another children’s theater company that is producing here in New York with people in New York and wanting to keep it here,” Stevens said. “We don’t want to tour; we seriously want to be the theater of Manhattan for young audiences.”

Indeed, the theater’s first season proved surprisingly successful: more than 6,000 customers came through their doors. This enabled a rarity in non-profit theater work, a balanced budget. Fifty percent of that budget they earned through ticket sales alone. Thirty percent came from individual and corporate donors and grant money supports the remainder.

Even so, Stevens admits, “Money is a challenge. It will always be a challenge, especially with the rent we’re paying.”

Other difficulties abound. The apartment they use, which they rent from the Access Theater Company, presents a number of artistic dilemmas.

“That space itself is a very unique space,” said Christie Phillips, the art director. “It used to be a gallery. It’s got hardwood floors that we can’t nail into, plaster walls that we can’t screw into, we can’t hang anything from the ceiling, and big gorgeous windows that we sometimes have to cover up.”

Finding publicity can also be hazardous: like most theater companies, they rely on free newspaper listings for much of their advertising, which, Merrill said, “means we’re at their mercy if they need to bump us for a week.”

But with those challenges come several advantages unique to theater for children. Simple demographics offer one: according the Department of City Planning, more than 200,000 kids under 18 live in Manhattan alone. And, partly because the Manhattan Children’s Theater is clearly filling a need in the city, donations have been coming in generously and the incorporation process proved less painful than Merrill and Stevens had anticipated.

But beyond the prosaic benefits, children’s theater offers creative opportunities that are often elusive on the adult stage.

“I like to incorporate elements out of the ordinary—like music and dance,” said Merrill. “So children’s theater very much allows for that; you can be extremely imaginative.”

Phillips agreed. “Kids I think are willing to take a lot of those leaps with you that adults aren’t,” she said.

But that doesn’t necessarily mean they’re gullible. For instance, she explained, she constructed all the trees in “Goblin Market” using chicken-wire frames with strips of cloth woven through them.

“I think that for an adult, that’s not very literal, not very realistic, but I think kids definitely appreciate that kind of versatility of materials,” she said. “I’ve designed a lot of shows for theater for adults and if you don’t have a lot of money and you have to design someone’s living room, it’s a lot different from not having a lot of money and having to design an enchanted forest.”

Perhaps it’s this creative license that allows the Manhattan Children’s Theater, despite budgetary anxiety and an occasionally oppressive work schedule, to remain an optimistic lot.

“Some weekends are better than others,” said Stevens. “But we’re still a young company. Younger than most of our audience members. They’ll grow with us.”