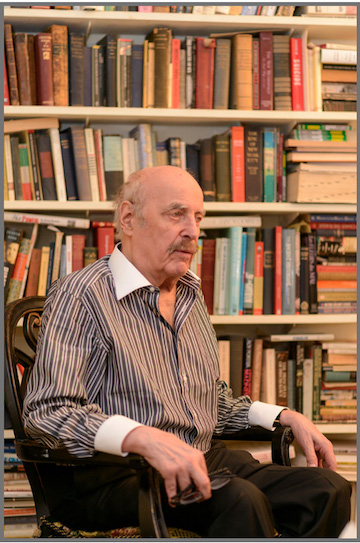

BY ANDY HUMM | Psychotherapist George Weinberg, who coined the word “homophobia” in 1966 — turning the tables on anti-gay people by branding them as the sick ones — died in Manhattan on March 20 at age 87. Weinberg, who lived and worked on the Upper West Side for decades — seeing patients up until the time of his death— had just completed an article for Gay City News, sister publication to Manhattan Express, on the origins of his famous word.

In his groundbreaking “Society and the Healthy Homosexual” in 1972 — a year before the American Psychiatric Association dropped homosexuality from its Index of Mental Disorders — Weinberg’s first line was: “I would never consider a patient healthy unless he had overcome his prejudice against homosexuality.” Weinberg himself was heterosexual and understood their fears and prejudices well.

Almost all that was available in libraries from people in his profession at the time were what now have to be considered quack tracts on how homosexual desire was perverted and that prescribed deeply harmful “treatments” such as lobotomies and electroshock to overcome it. Weinberg’s approach encouraging self-acceptance — and telling gay and non-gay people to overcome their fears of homosexuality — was revolutionary and gave solace and dignity to millions. While Stonewall Rebellion in 1969 represented a defiant act of self-liberation that catalyzed the LGBTQ movement, Weinberg’s book reached bookstores and libraries across the country with a message that transformed gay psyches and greatly expanded the numbers demanding equality. Early activists picked up the term “homophobia” and popularized it.

Jim F. Brinning, a longtime Boston gay and AIDS activist, related a typical experience with Weinberg’s work. “Dr. George Weinberg saved my life,” he wrote on Facebook. “He was a big reason I came out. I struggled with who I was as a kid, bullied at school and at home. In the early ‘70s I had to figure out if I was sick or not because I felt like I would explode. In the early ‘70s I’d go to the library in my hometown of Montclair, NJ, and looked up everything I could about homosexuality. Everything was so negative. Then I found listed ‘Society and the Healthy Homosexual.’ I couldn’t believe what it was saying, it told me everything I had been feeling since a little boy was normal. Trying to repress who I am was abnormal. I took the book home and read it several times. It was an anchor. I didn’t check the book out of the library because I was too embarrassed, so I hid it in my jacket. That was in 1973, the year I came out.”

Dr. Jack Drescher, MD, an out gay psychoanalyst and emeritus editor of the Journal of Gay and Lesbian Mental Health, wrote in his “Psychoanalytic Therapy and the Gay Man,” “George Weinberg has left an indelible mark on the world. His formulation of ‘homophobia’ transposed the medical model in a novel way: If same-sex attractions are not a mental illness, then perhaps intolerance of homosexuality might be considered one instead. George ingeniously demonstrated how a 20th-century theorist could construct a new clinical syndrome in the same way that 19th-century scientists created a disease called ‘homosexuality.’ For this and so many other things he will be missed.”

Chapters in Weinberg’s ‘72 book included “The Bias of Psychoanalysis,” where he described and then destroyed the offensive theories on homosexuality held by Freud and his own contemporaries, including Dr. Lawrence Hatterer who had written, “I’ve seen some very destroyed human beings who have felt the ravages of attempts to sustain a permanent homosexual relationship.” Of course, all of these charlatans based their diagnoses on the troubled gay men and women who came to them in a society almost universally hostile to them. Many of these people did indeed seek to “change” in order to survive in the pre-liberation days. But despite claims that they could alter sexual orientation, the consensus is that such changes are impossible. Indeed, Weinberg devotes another chapter to “The Case against Trying to Convert” and in recent years supported laws to ban so-called “conversion therapy.”

Weinberg often said that many in his profession never let go of their deep-seated feelings that there was something wrong with homosexuality, even though the official position of their professional associations is that homosexuality is a normal variation in human sexuality.

Weinberg was aided in his formulations in the pre-Stonewall era by having self-accepting gay friends — and knowing other gay people who were hindered in life by their lack of self-acceptance. In his training as a psychotherapist, he refused to go along with the accepted clinical practice of trying to “change” homosexual patients — going so far as to turn off the tape recorder his superiors would review when evaluating him in order to encourage a gay patient to embrace his or her orientation.

It was at the 1965 conference of the Eastern Homophile Movement in Manhattan that he really connected to the pioneers of the movement. There, he befriended and began working with activists including Frank Kameny and Jack Nichols, who had co-founded the Washington chapter of Mattachine Society in 1961, and Lilli Vincenz, the group’s first lesbian member.

Veteran New York gay activist Steve Ashkinazy wrote in an email, “When that book came out in 1972, Dr. Weinberg agreed to help the Gay Activist Alliance hold the very first serious, professional gay fundraising event ever — a book signing cocktail party” at Weinberg’s home on Central Park West where he also practiced… They asked people to write checks. But NO ONE would. They gave up their pocket change: 5 and 10-dollar bills. But no one would write a real check, for fear of the paper trail that could potentially identify them and publicly out them.”

Weinberg was involved in the early LGBTQ rights movement, testifying for the New York city gay rights bill the year it was the first one to be introduced anywhere in 1971. He participated in the first march in 1970 commemorating the Stonewall Rebellion, telling Drescher, “I even tried to get a therapist friend of mine to go to the first gay march. He finally went with me to Sheep’s Meadow, where the parade ended up. A world famous therapist — I thought he was going to pass out. All those people coming up to me saying, ‘Let me give you a hug.’ I thought he was going to die.”

In 2012, the Associated Press officially discouraged its reporters from using “homophobia” in its stories (a policy recently discarded) and Weinberg took them on in Gay City News, writing, “The AP’s recent dislike of the word because it is ‘political’ makes no sense. It is political because a large number of people have brought it to light and are opposing abuse. If one man beats up his wife nightly because he’s a drunk, it isn’t political. It is personal. If a million do and women organize in protest, it’s political. But it is still personal and psychological. ‘Political’ just means that many people are trying to do something about it. Homophobia doesn’t lose its status as a phobia just because many people are now on to it and are trying to cure it or to live in spite of it.”

George Weinberg was born May 17, 1929 in Manhattan to a father who quickly abandoned him and a mother, Lillian Hyman, who raised him well on her own. He often joked that he was a “disturbed child” because he was sent to a special private school and told Drescher in an interview that he “did very badly in school in everything except math and English” at DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx and City College, where “as a lover of poetry” he “first met gay men.” He went on to a graduate work in psychology at Columbia and in English from NYU, starting a private psychotherapy practice in the 1960s.

“The gay issue tormented me,” he told Drescher, “not only because I was making gay friends who were suffering hideous, marginal lives, and the police weren’t doing anything to help them, but I was also learning that many of my heroes throughout history had been gay. I thought about Houseman, Shakespeare, probably Jonathan Swift. I didn’t yet know about Newton. So many of these people had to have lived fearful, guarded lives. I think my having been labeled ‘disturbed’ in my own childhood had greatly increased my sympathy and understanding. The minute someone was called ‘disturbed’ or ‘abnormal,’ it became fascinating to me because it meant that this person was being was marginalized.”

Weinberg was the author of 14 books on a range of topics, from popular psychology to William Shakespeare, from whose work he could quote extensively from memory and who he had no doubt was gay. He wrote “Will Power: Using Shakespeare’s Insights to Transform Your Life” with his wife Dianne Rowe, who survives him.

The Los Angeles Times reviewed Weinberg’s “Invisible Masters,” calling him “the kind of psychotherapist one might like to have — engaging, animated, mindful of the part his own personality plays in any exchange, sensitive, and thoughtful.”

I had the honor of getting close to him as a friend and editor over the last 12 years and can testify to all of those qualities. Even as his health declined in recent years, he never stopped writing or seeing patients, or engaging in the controversies of the day.

“I’ve always subscribed to Nietzsche’s line,” he told Drescher. “Society is advanced by those who oppose it.”

Rowe said, “One of George’s favorite phrases was from Keats [‘When I Have Fears that I May Cease to Be’]: ‘The faery power of unreflecting love.’ ‘Faery’ meaning magical. He loved with great immediacy and never judged or reevaluated people. He loved his patients and his friends all of his life.”