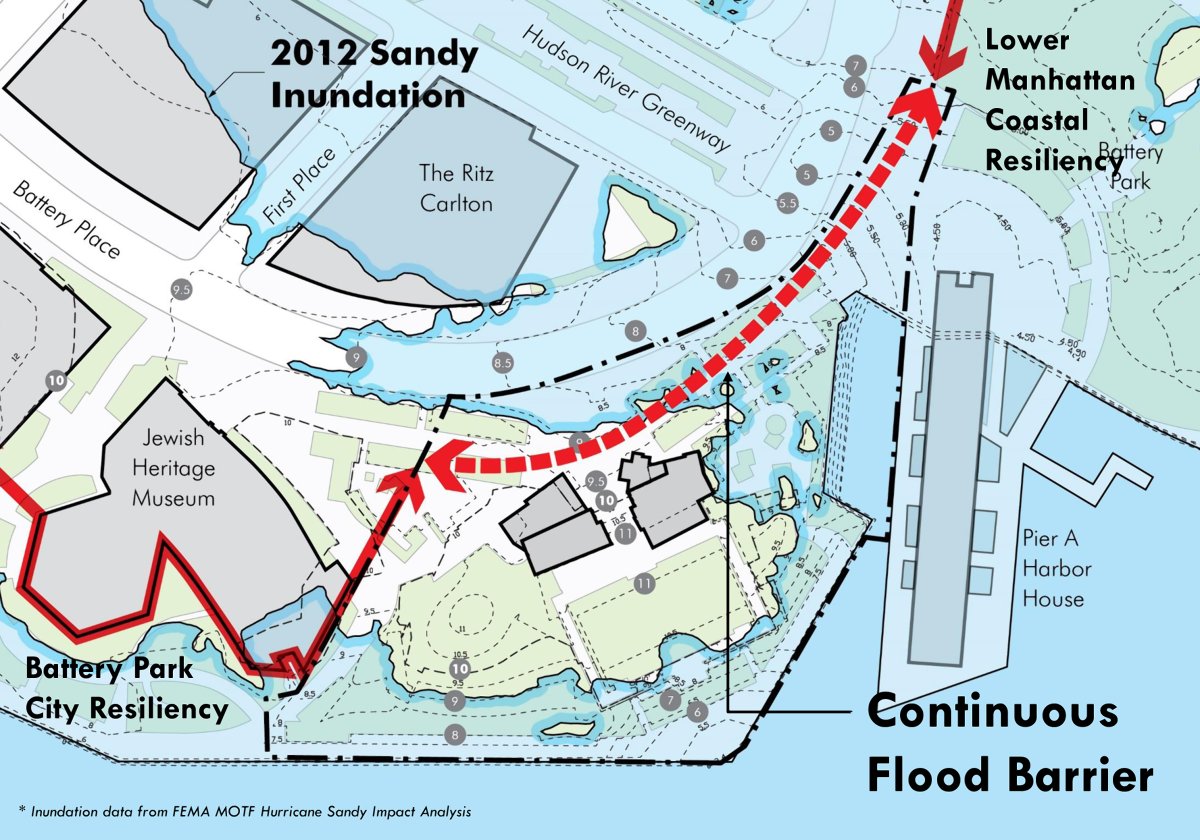

This map shows the extent of flooding in Wagner Park during 2012’s Hurricane Sandy, and the location of a possible new barrier that may prevent a recurrence.

BY DENNIS LYNCH

Battery Park Citizens worry they may lose a precious redoubt in Wagner Park after seeing some of the proposed resiliency measures and park improvements that the Battery Park City Authority presented to Community Board 1’s Battery Park City Committee that would keep out storm surges, but likely bring in far more tourists.

Architect Stanton Eckstut, the original master planner of BPC and now a principal at Perkins Eastman presented the results of his firm’s study of the park at the committee’s Dec. 6 meeting, and he offered two sets of preliminary objectives — those to make Wagner Park more resistant to storm surges, and those to make it more inviting to visitors.

Most people at the meeting agreed that the park should be made more resilient, and agreed with Eckstut that grading the lawns upward from the waterfront and installing a semi-permanent flood wall were appropriate changes, but they were less enthusiastic about the other suggestions from Eckstut’s team.

Those suggestions were said to be based on an April survey taken by 414 people — but only 268, or a about two thirds, were BPC residents — and on conversations with local stakeholders.

Less than a third of survey respondents wanted more food and beverage options and more activity programming, but nonetheless, Eckstut and his team suggested creating more restaurant space and adding infrastructure for boat access at the waterfront.

He also said the Esplanade could be connected to Pier A to facilitate the flow of people and suggested the park could be reconfigured in some ways to make the park more pedestrian friendly.

But several CB1 members worried that some of those changes, particularly connecting to Pier A, would serve only to attract more tourists to Wagner Park and the Esplanade, which many BPC residents see as their last safe havens in a neighborhood that feels increasingly besieged by outsiders.

“It’s the one place that has less activity, and that’s a good thing,” said BPC Committee chairwoman Ninfa Segarra. “I like the fact that tourists can’t figure out how to get from Pier A over to us because it limits [traffic]. The truth is we’re overwhelmed here with tourists,”

Segarra highlighted the increasing conflict between managing the public spaces of BPC in the interests of residents versus the interests of tourists and the city’s economy.

“We understand its great for the city, great for the economy,” she said, “but the volume has become a real quality-of-life issue.”

One Battery Park City resident echoed that sentiment the next day at the first BPCA meeting to allow public comment. The Cove Club resident objected to the BPCA’s proposal to pave a green cul-de-sac at the end of South End Ave. near her building to create a public pedestrian plaza on the grounds that it would only serve to attract more tourists to the neighborhood.

Some board members also took issue with the resiliency proposals — or at least the timing of them. The city, state, and federal governments have undertaken a massive resiliency plan for much of Manhattan, but a detailed blueprint for Lower Manhattan has been slow to materialize. Funding is not in place for much of the project, nor is there a clear vision of what exactly the resiliency plan will entail.

The BPCA should wait until that plan comes together so it can fit its plan for Wagner Park and the rest of the neighborhood into it, otherwise it could complicate the larger resiliency project, board member Tammy Meltzer said.

“It would be a shame to have whatever is done for Battery Park City hurried and done within five years, and the city comes along in 10 and says it has to be integrated and changed,” Meltzer said.

Eckstut said he wasn’t putting the cart before the horse. The huge undertaking of making Manhattan more resilient means projects will inevitably develop separately and at different paces, he said.

“I deal with a lot of large-scale projects. You can’t wait until everything is all solved,” he said. “What is important is that you’re consistent with policy, reaching out, and informing the people. But things are going to be done, whether by the authority or other entities in different time periods, its very real with anything this large.”

BPCA spokesman Nick Sbordone said in a statement that “doing nothing was not an option” and that in the effort to make the park more resilient, “we also want to make sure to make the park and buildings within it as inclusive of residents interests as we can — as evidenced by the questions included in our Wagner Park survey and the series of ongoing public forums on the topic.”

Eckstut admitted he was surprised to hear the opposition to some of the non-resiliency suggestions for the park, but that he was “all for” further engagement to inform his proposals. Locals will next get a chance to do that sometime early next year at a planned public discussion and feedback session hosted by the BPCA. Feedback can also be directed at info.bpc@bpca.ny.gov.