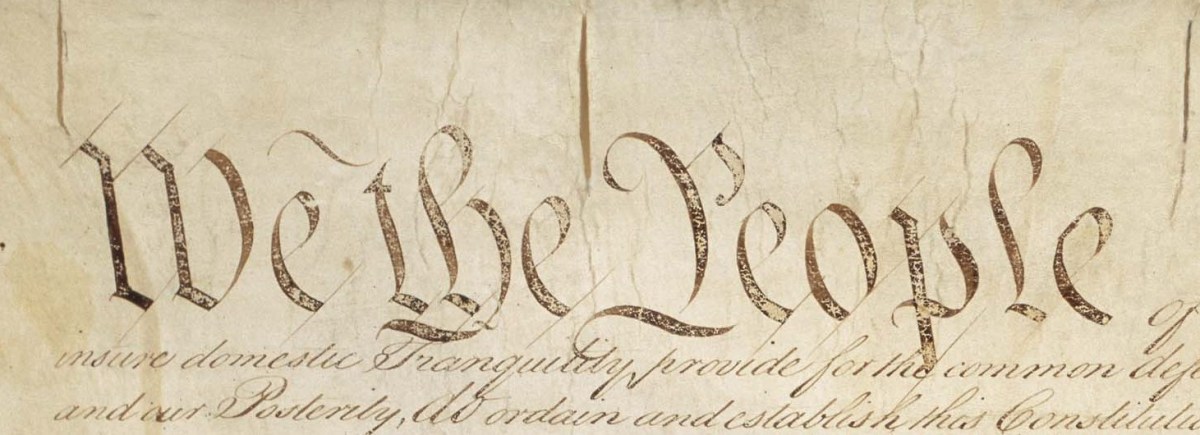

BY LYNN ELLSWORTH | The phrase “We The People” in the Constitution still has the power to wake the sleeping idealist within us. It’s a clarion call to our better nature, to get off our asses and bend the arc of history toward something better, to come together to make decisions for the general welfare. It evokes raised hands at town halls, voting booths, Athenian debating assemblies of 5,000 people, and ancient fields where men assembled and banged their shields to indicate their assent — or not — to a call to war.

“We The People” conveys fairness: a political community with the right to gather and figure things out. It is why we are so enraged that the Electoral College renders our vote pointless, why newcomers to New York City are shocked to learn they cannot elect community board members, why women gathered in Washington, and why disenfranchised groups throughout history took to the streets demanding to be part of “We The People.”

It is also why many New Yorkers are contemptuous of the use of the fake participatory community-planning “processes” that have become popular among city politicians. There are many types of such processes, ranging from the participatory-budgeting sideshow that even Brian Lehrer on WNYC has made fun of, to the tightly curated and controlled “working groups” set up to create the illusion of community approval for rezonings. Such groups were used for the South St. Seaport, Midtown and East Harlem, and a new one has been set up for the unneeded Soho rezoning. Now there are also the micromanaged “neighborhood advisory groups” that the mayor created to thwart opponents of the expensive new tower-jails.

Representative and indirect forms of democracy make sense when the geography is vast and communication difficult. Scholars think that is why our founding fathers created the Electoral College in the first place. How else to manage national voting in a vast country with rough roads and no Internet?

That also means that representative, indirect democracy makes little sense when the geography is as small as a neighborhood. Athens at the peak of its democracy only had 30,000 people! So, surely, city dwellers in the modern era can find a way to have some substantive direct democracy at the neighborhood level. Technology like Placespeak makes neighborhood referenda easier than ever. And even Los Angeles manages to have elected neighborhood councils, so why don’t we? Of course, city politicians will resist local democracy: It would take some powers on local matters away from them. But it has to happen. On local matters, appointed commissions, boards and advisory groups just lack the basic legitimacy that comes from direct democracy. So it is worth imagining: Which powers and decisions might be delegated to elected neighborhood councils or made via local referenda?

For example, we might give neighborhoods more power over the management of public spaces — sidewalks, street parking, stoplights, the placement of crossing guards, the organization of trash pickup, street trees, bike racks, parks, public-private plazas. We could also give residents power to veto egregiously out-of-context buildings, the right to say no to buildings that require spot rezoning and the right to veto air-rights transfers that result in an excessive breach of contextual height limits. Use your imagination!

Our city democracy has become too representative, taking too much power away from “We The People” at the most local level. To change that, community-based planning must begin with democracy at the neighborhood level, with every resident having the right to raise their hand or bang their shield on local issues that matter.

Ellsworth is chairperson, Tribeca Trust, and president, Human-Scale NYC