BY CORMAC FLYNN | “There is a difference between remembrance of history and reverence of it.” With this pithy sentence, New Orleans Mayor Mitch Landrieu summed up the distinction that the country has been struggling with in a myriad of cases over the last few years: the Confederate battle flag, the names of buildings and schools on college campuses, statutes honoring problematic people or renounced causes, etc.

As local activists move to displace reprehensible historical figures from positions of honor, opponents predictably decry “erasure” and warn of a slippery slope. If you take down a monument to Klan founder Nathan Bedford Forrest, they warn, you’ll have to take down monuments to Washington and Jefferson, who, after all, were slave masters.

The answer from liberals and progressives like myself has been a variant on Landrieu’s eloquent summation: There is a difference between honestly presenting history, warts and all, and celebrating those warts as achievements and role models. There is a difference between honoring someone who is flawed for a specific good they did and exalting them specifically for the flaw. Another criterion is whether the repugnant acts were what the individual is chiefly known or remembered for. In other words, it doesn’t wash to say, “Hey, I’m just honoring Hitler for his service to auto travel.”

In the campaign against “Lost Cause” propaganda in particular, we have avoided any slippery slope by keeping moral footings. Taking up arms against our elected government, for example, is treason. And murdering civilians to stoke fear for a political purpose is terrorism. Also, service in evil causes is never praiseworthy; an individual might be forgiven, or even redeemed, but the shameful actions themselves should not be honored.

Which brings me to Oscar López Rivera and New York’s own Puerto Rican Day Parade.

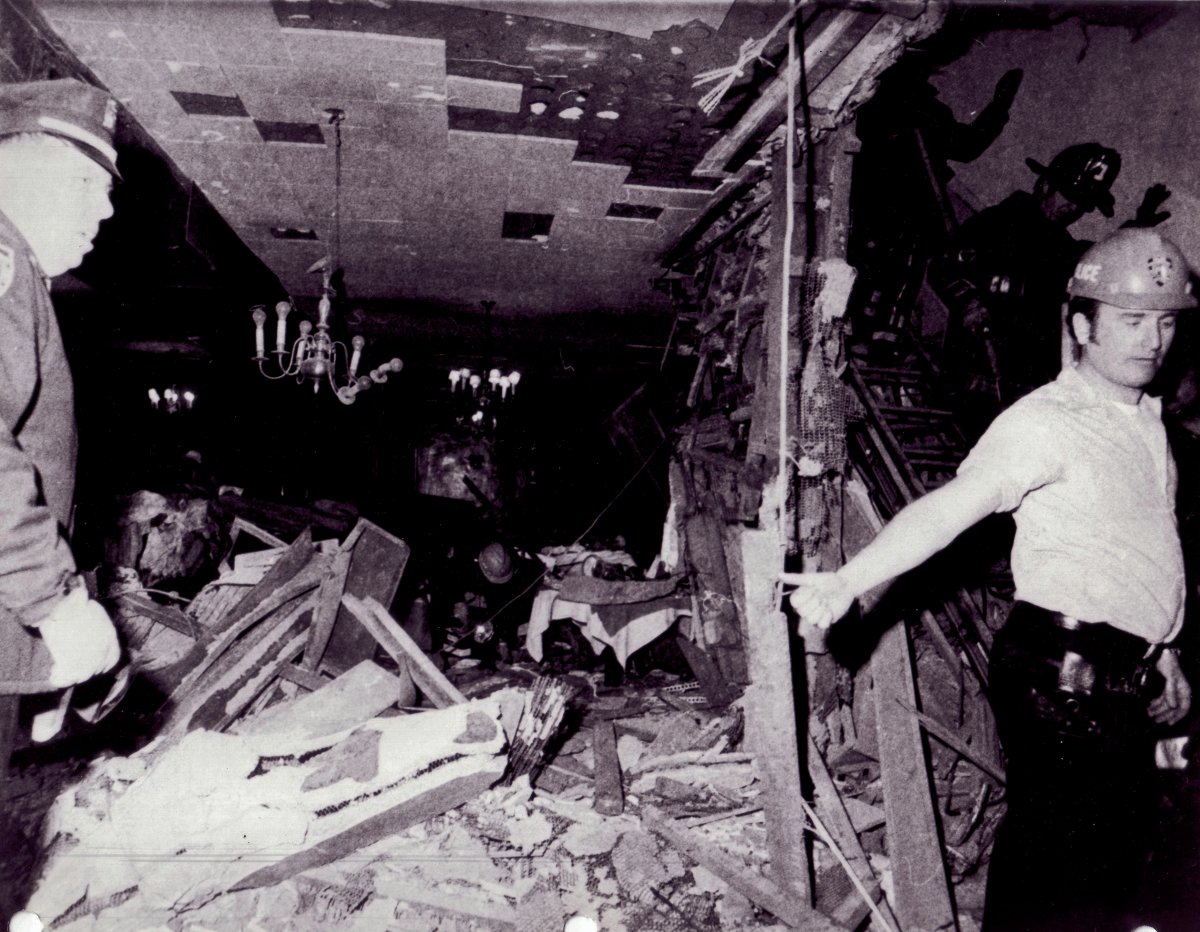

López Rivera was a terrorist. His organization, the FALN, was responsible for more than 120 bombings in the U.S. between 1974 and 1983 in its quest to impose a Stalinist dictatorship on Puerto Rico. Among the most notorious of these was the brutal 1975 lunchtime bombing of historic Fraunces Tavern in Lower Manhattan. Four people were killed, dozens injured.

That same year, in a scene eerily similar to recent footage from Europe, police found Rivera’s apartment loaded with explosives, weapons, bomb-making equipment and targeting photos of high-profile public places. Apprehended and tried in 1980, he openly admitted to all charges against him. He expressed no remorse.

López Rivera was sentenced to 55 years; a later escape attempt earned him 15 more. Social-justice and human-rights advocates became concerned that López Rivera’s lengthy incarceration was out of proportion to his specific convictions. In 1999, President Bill Clinton offered clemency on the condition that López Rivera renounce political violence. Fourteen of his 15 former FALN comrades agreed, but López Rivera would not. President Barack Obama commuted López Rivera’s sentence earlier this year — which should have been the end of his story: By the mercy of a great nation, a 74-year-old man is freed after 35 years, so he can finish his days quietly at home.

But now, López Rivera is to be honored in the Puerto Rican Day Parade.

When I say, “honored,” I am bearing in mind Mayor Landrieu’s distinction between memory and veneration. López Rivera has not been invited as, for instance, a symbol of the need for criminal-sentencing reform, a guilty man who nevertheless deserves fair treatment. Nor is he being presented as an exemplar of repentance: Rivera remains Trumpian in his defiant self-pity. Nor does he seek to make amends: The New York Times quoted him just this month refusing to apologize to the families of FALN victims and, in fact, complaining that they should show him more respect.

No, López Rivera is to be honored as the parade’s first “National Freedom Hero,” a superlative specifically created for him by the organizers. You know — for all that heroic bombing of innocents in pursuit of dictatorship.

It is really hard to see how this is different in principle from obnoxious celebrations of the Confederate cause in Southern cities and towns. Think about it: López Rivera is to be given a public triumph in a city he terrorized — a city still vigilant to bombs and blanching at every firecracker — in the name of heritage and ethnic pride. All that is missing is the Stars and Bars.

The scope and impact of the FALN’s reign of terror pale beside those of the Confederacy and the Klan, though that is little comfort to its victims. Race and privilege must also be taken into account. The glorification of terrorism by the white majority is obviously more dangerous to society than similar behavior by the long-marginalized Puerto Rican community. Yet, the principle is the same: the sanctioned adoration of thugs and killers who reject our core values of human rights, law and democracy.

Oscar López Rivera was a terrorist, as Nathan Bedford Forrest was. López Rivera was a traitor to the United States, as Robert E. Lee was. López Rivera does not renounce his shameful past or pledge himself to the cause of those he harmed, as James Longstreet did. Indeed, he is known for no other commitment than to the FALN. It is for that reprehensible conspiracy of violence, terror and totalitarianism that he is being honored.

If he was a statue, we’d tear it down. And we’d be right, too.

Flynn is the principal at Act for Change, an executive coaching and strategy consulting firm, and co-chairperson of the W. Eighth St. Block Association