Even though he only served eight months as the editor-in-chief of the Daily News, Pete Hamill left an indelible mark on those he worked with and served as an inspiration for countless journalists.

The teller of great stories was even brought back to write about witnessing the Sept. 11, 2001 terrorist attacks. In a column for the Daily News, in which this writer’s photos were featured, he recalled being at Tweed Courthouse near City Hall that fateful morning and running out just in time to see United Airlines Flight 175 hit the South Tower.

No matter where Hamill landed afterward, his words and books filled the libraries of many of his colleagues, most notably “Snow in August,” set in a working-class Brooklyn neighborhood in 1947 revolving around two of the endearing characters in fiction: an 11-year-old Irish Catholic boy named Michael Devlin and Rabbi Judah Hirsch, a refugee from Prague.

His works left a huge mark on his colleagues, but it was his warm, generous and caring attitude towards those working with and for him that left memories and inspiration.

Hamill is also remembered for his short stint at the New York Post before becoming editor at the News. Amid mass layoffs in the early 1990s, he refused to step down as editor and moved his desk to a diner near the newsroom in protest of then-owner Abe Hirschfeld. He actively wrote stories making Hirschfeld, a parking lot magnet, the laughing stock of the city.

But during his short time at the Daily News, he left an indelible mark.

Joanne Wasserman, a former Brooklyn bureau editor for the Daily News, remembered her time as a reporter under Hamill. She recalled his ability to listen to detail.

“I remember the interaction with him and particularly when I had an idea about a story about my own son, Sam, looking for a school for him because he had special needs,” Wasserman recalled. “I told him about it, and he took a special interest and talked me through it – he saw my emotion about it. I’d been through a lot and he made sure I came off as generous, thankful and not resentful. He made the piece better – he made me understand that you can be smart and generous – both things.”

The piece about having special needs students being inclusive in school and not being singled out had a profound effect on education. Her son went on to attend Sarah Lawrence College and become a great writer in his own right.

That relationship didn’t end there. About eight months later, Wasserman invited Hamill to read Snow in August at her school fundraiser – his mother only recently had died.

“When he got out of the car, people mobbed him from the Park Slope neighborhood and people were shouting, ‘I knew your mother’ – a nice welcome back to Brooklyn,” Wasserman said of the Brooklyn born scribe.

Stuart Marques, a former managing editor for the Daily News, said Hamill was “the reasons why I and so many of us went into journalism.”

“He was always encouraging me and other young writers – I remember him working with us during the subway series – he was such a pleasure to work with,” Marques said. “I remember him when I was still in college, he was such a mensch.”

Michael Lipack, former Daily News deputy photo editor, remembered Hamill as a huge supporter of the photo department and of ‘great photography.’

“He cared about projects and while I only worked with him for a short time, he showed how he cared by supporting great works,” said Lipack, recalling one particular project by photographer Susan Watts about a crack addict named Gloria whom Hamill provided eight pages of coverage, including a Sunday cover.

“I went away for a month to photo school and before I left, he put his arm around me and he said, ‘I’ll see you in a month,’ but then he was gone when I returned. We lost one of the great ones that day – bad for the photo department and bad for the paper – a great man.”

Watts said the story on Gloria “would never have seen the light of day without Pete.” The photo array and story by Linda Iglesias won Watts top honors in World Press Photo competition that year.

“After my first day of the shoot, we printed out the pictures and walked into Pete’s office, and he said, ‘Let me know when you’re done – go do the story,” she recalled. “Not only did he create a special section, eight pages devoted to a drug addict prostitute, but in the Sunday paper cover of the Daily News for people to read while eating their corn flakes in the morning.”

Watts became closer with Hamill during that time and would be able to walk into his office and toss around ideas as he was “a champion of great photography.” She went on to photograph the wedding of Hamill’s daughter, Adriene Tuthill, in upstate New York and stayed with the family in their home. She also photographed the cover of a book written Fukiko Aoki, Hamill’s wife, a story about a dog.

“Pete was once in his office and he put some story about a dog in the front of the paper, and Jimmy Breslin called him saying, “Eight million people are all suffering, and you put a goddamn dog on page 3.’ I remember Breslin then hung up the phone.”

She also remembered Hamill taking a call from an elderly woman subscriber – somehow the call got to his office. She described how the paperboy (Hamill started out as a paperboy for the Brooklyn Eagle), would throw the paper landing far from her doorway, sometimes getting wet in the rain.

“He would listen and speak with her and she was really angry- he was so generous and told her how it should never happen – I’m sure he did something about that – he was such an inspiration,” Watts said.

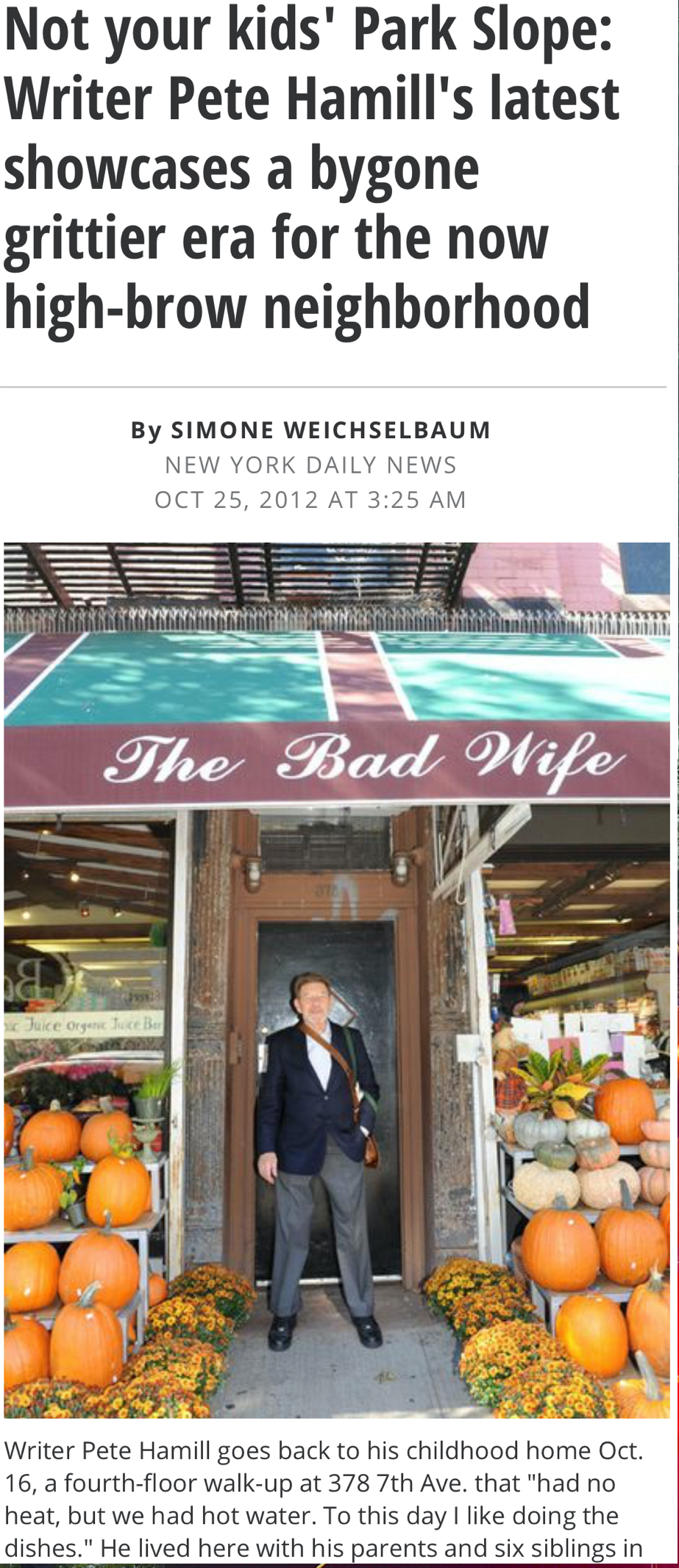

Debbie Egan-Chin, a former photographer staff member, remembered on a story with reporter Simone Weichselbaum in October of 2012 in which Hamill went back to his old home in Park Slope which was a “bygone grittier era,” a former tenement, but now multi-million-dollar high-brow walk-ups.

“We had access to the apartment from the people who lived there and he sat at a table and he talked about his life living there with his large family in that railroad apartment on Seventh Avenue,” Egan-Chin remembered. “When we walked up the stairs, you can hear every creek and he would talk about the kitchen in the rear of the cold-water flat and you could just feel how it was listening to his description. He could make you feel it in his words and writing.”

Personal note: I also knew Pete Hamill both from his days at the Daily News and from his work in the streets.

As a struggling freelancer in 1997, Hamill would come up to me in the newsroom and pat me on the back and tell me ‘you did a great job, thank you.’ You didn’t get that very often from other top editors other than from your immediate supervisors on the photo desk. I won Photographer of the Year from the New York Press Photographers Association for my work that year – mainly due to Hamill for supporting great photojournalism.

One of the many sad days at the Daily News was when Hamill was forced out by Publisher Mort Zuckerman over editorial differences. Hamill stuck by his guns and was a man of conviction, not wanting to give huge coverage of the British royal family or Princess Diana – a final straw at the time being both his insistence on running a huge Norman Mailer piece in the paper and his refusal to do a story on Princess Diana’s gowns.

But Hamill was never far away, as he came back to write about the 9/11 World Trade Center attack, something that has been an indelible mark on many of us, and in which my photos were prominently featured.

Watts recalled that moment Hamill sitting in the newsroom and he commented to her, “we are alive and reporting an important time in history. We are witnessing history.” He was so right.

I was saddened to have appeared in his documentary with Jimmy Breslin, “Breslin and Hamill: Deadline Artists” – my photo featured with 96 other reporters and photographers who lost their jobs in 2018. I only wish I’d been in a more upbeat part of this great documentary – he was an inspiration for all in our profession.