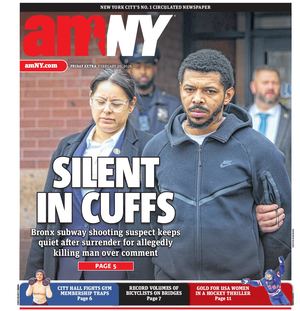

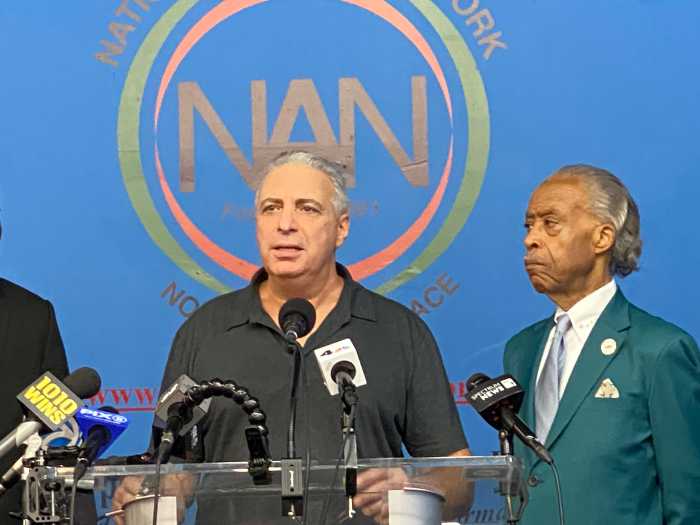

Families of Harlem residents killed in the city’s recent Legionnaires’ disease outbreak stood alongside Rev. Al Sharpton and attorneys Tuesday to demand accountability for what they call a preventable tragedy and a civil rights issue.

Civil rights attorney Ben Crump and lawyers from Weitz & Luxenberg said their caseload has grown to 35 clients, including four families of deceased victims and four hospitalized construction workers.

As of Aug. 29, city health officials confirmed 114 cases, 90 hospitalizations, and seven deaths tied to the outbreak, which was traced to cooling towers atop Harlem Hospital and a nearby laboratory construction project.

The tower installed on the construction site — overseen by Skanska USA — went online in May but was never registered with the Department of Buildings or the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, according to the legal team.

Attorneys representing victims say the official numbers may be underreported, citing possible uncounted pneumonia-related deaths and delayed diagnoses during the outbreak window. Jared Scotto of Weitz & Luxenberg said, “The Health Department can’t test what they don’t know about… We need to know what else wasn’t done to protect Harlem residents.”

Standard safety protocols require cooling towers to be visually inspected three times a week, tested for bacteria monthly, and cultured every 90 days. Scotto claimed Skanska’s failure to follow these rules allowed Legionella bacteria to flourish.

Crump announced on Sept. 23 an additional lawsuit against Skanska on behalf of another construction worker, along with 17 notices of claim, including several wrongful death claims.

The Sept. 19 lawsuit was filed on behalf of Thomas Dawson, a New Jersey man who worked at the construction site and became sick with Legionnaires’ disease.

It follows earlier lawsuits, filed in August, involving construction workers Nunzio Quinto and Duane Headley, who were exposed to Legionella at the lab project next to Harlem Hospital.

Both allege severe illness and claim Skanska and contractors failed to maintain safety protocols or warn workers. Notices of claim were also filed against the city for lapses in inspection and notification.

In response to a query from amNewYork, a spokesperson for Skanska said it could not comment on pending litigation “or discuss the specifics related to this issue.”

“First and foremost, our hearts go out to all the families who have been impacted in this recent Legionnaires outbreak,” the company said. “Skanska has worked in close coordination with the DOHMH to facilitate the disinfection of the cooling tower at our jobsite. Throughout this process, the DOHMH has monitored our efforts, ensuring full compliance with their protocols.”

A City Hall spokesperson said that it would review any lawsuits “once they are received.”

“We mourn those who lost their lives, and our thoughts are with their loved ones. Thanks to our swift efforts, we were able to save countless more lives in the face of this outbreak,” the spokesperson said. “As we prepare for any future outbreaks, we have put forward concrete actions we are already taking to improve all aspects of this process and support proposed legislation to strengthen laws and requirements for building owners, which are already among the strongest in the country.”

At a Friday City Council oversight hearing, health officials defended their handling of the outbreak. They acknowledged that tests for Legionella bacteria are imperfect but that their response helped limit harm.

Acting Health Commissioner Michelle Morse supported proposals for more frequent cooling tower testing, from every 90 days to every 30, especially during heat waves, but cautioned there’s no way to reduce risk to zero.

“We can, of course, always improve upon our process. This summer’s events only underscore the need to look at how we can further protect New Yorkers and work to ensure all requirements are followed. We recognize, too, that Upper Manhattan and the Bronx have shouldered a disproportionate burden of Legionnaires’ disease clusters in New York City history,” Dr. Morse testified.

“There is no one cause of inequities in Legionnaires’ disease—but there are a few different factors that contribute to that pattern. One is that Upper Manhattan and the Bronx have a high population density. Another is that these neighborhoods have experienced consistent, long-term, generational disinvestment due to structural racism,” she said. “As a result, we see higher rates of chronic disease and differences in the built environment, which puts residents of these neighborhoods at an unfairly greater risk of Legionnaires’ disease.”

Deputy Environmental Health Commissioner Corinne Schiff said staffing shortages in recent years have contributed to reduced inspections, but rejected claims that more inspections alone would have prevented the outbreak. They also acknowledged that the tower overseen by Skanska USA had not been registered as required under the law.

‘Fight to learn the truth’

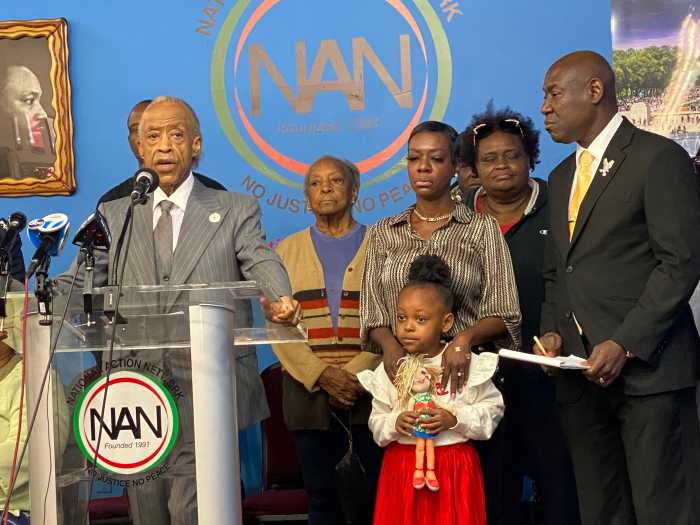

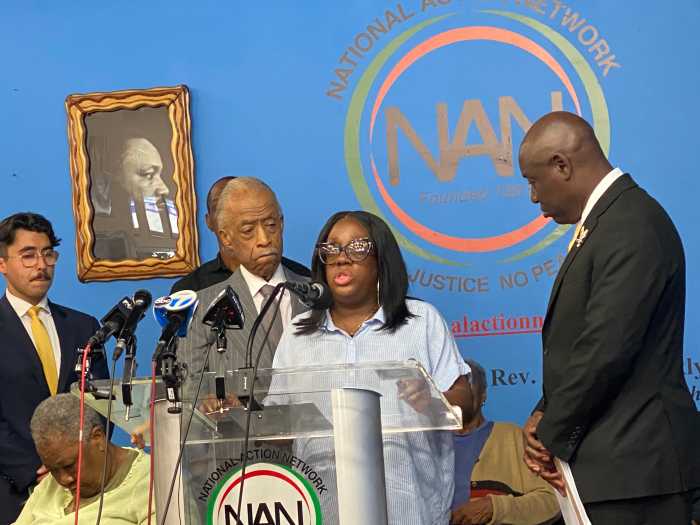

On Tuesday, at the National Action Network’s Harlem headquarters, families recounted the harrowing toll of the outbreak over the summer.

One mother described losing her husband after weeks of misdiagnoses, initially told he had pneumonia or heart problems. Her six-year-old daughter now faces life without a father.

“My daughter needs to understand why her dad is not here,” Lakisha Plowden, the mother of six-year-old Brooke Scott, said through tears about losing her husband, 53-year-old Bruce Scott.

“He wasn’t someone who ever got sick,” Plowden said. “He fought COVID twice without symptoms. But this was different; I knew something was wrong. He had chills, he had fever. We took him to Harlem Hospital, and the next thing I knew, I’m looking at him with a tube down his throat. The doctors brushed me off, said it was pneumonia, but gave me nothing in writing. His death certificate listed causes that didn’t match what really happened. A month later, we finally learned from the Department of Health that it was Legionnaires.”

Plowden described Bruce as “a family man, a provider, a great dad” who walked his daughter to school and never missed a school function. “Now my daughter has to grow up without him,” she said.

Crump called her ordeal evidence of a larger failure.

“What’s troubling is that she had to fight for a month just to learn the truth—that her husband died from Legionnaires’,” he said. “If she hadn’t persisted, the truth never would have come out. And his daughter deserves to know the truth. This outbreak has claimed lives, and we believe deaths are being undercounted. These were vibrant people until Legionnaires took them away. It was completely preventable, and that is the real crime.”

Nikia Bryant described losing her aunt, Rachel Tew, who entered Harlem Hospital on July 30 and died Aug. 3.

“She went in not feeling well, and never came home,” Bryant said. “They kept telling me they were running tests, but I got no answers. At Harlem Hospital, they said there was no room, so they transferred her to Metropolitan. She was alert, talking, and then suddenly, I got a call that she had gone into cardiac arrest and died. No one explained why.”

It wasn’t until more than a week later, while Bryant was on her way to work, that the Department of Health finally called. “They said, ‘I don’t know if anyone told you, but she died of Legionnaires’.’ I was standing on 125th Street when I heard that, and my heart felt like it was coming out of my body,” she said.

Bryant called her aunt “a fighter” and said the family is seeking accountability, not compensation. “This is not about money,” she said. “It’s about justice. We can’t bring our loved ones back, but we can stand up and demand the truth. Harlem may be a small community by name, but we are a big community, and our voices deserve to be heard.”

The family of Ronald Israel, who died at 40, was also present at the press conference.

Rev. Sharpton framed the outbreak as a civil rights issue, arguing the city would have responded faster if the crisis had occurred in a wealthier, whiter neighborhood. “If this had happened in another community, the outrage would be deafening. We will not allow Harlem families to be marginalized,” he said.

With the mayoral election weeks away, Sharpton called on every candidate to support the victims. “No candidate should have laryngitis on this issue,” he said, emphasizing that public health and justice are intertwined with leadership and accountability.

The families and attorneys vow to continue litigation and pressure city officials to be transparent about the full scope of the outbreak. They are urging anyone hospitalized or who suffered illness during the outbreak window to come forward.

“We want your voices to be heard,” Scotto said.

“The attorneys will call it medical malpractice. I would call it medical non-practice when it comes to black folks,” Sharpton said.

When asked if he believed the city avoided testing for Legionnaires’ disease in its hospitals, Sharpton said the city did “not aggressively try to make sure that this was being tested.”

“Why wasn’t it automatically tested? Since it was already publicly said, there was an outbreak,” he added.