A group of local disability advocates is making headway on a lawsuit against the City of New York that claims the city’s Open Streets program violates the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA).

Federal Judge Eric Komitee will hear oral arguments on Thursday from the plaintiffs, many of whom are members of the ADA-advocacy group NYC Access for All, and the defendants, including the NYC Department of Transportation (DOT) and other third-party groups. This marks a significant step in the lawsuit, which was filed in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of New York, also known as the Brooklyn Federal Court, on April 24, 2023.

The plaintiffs claim that Open Streets does not provide equal mobility access to public streets. Some members of NYC Access for All have called the program, which launched during the COVID-19 pandemic as a way for locked-down New Yorkers to enjoy open-air space, “ableist, ageist and elitist,” as it uses barriers and other heavy steel barricades that people with mobility issues can not lift or operate in order to enter the open-space area.

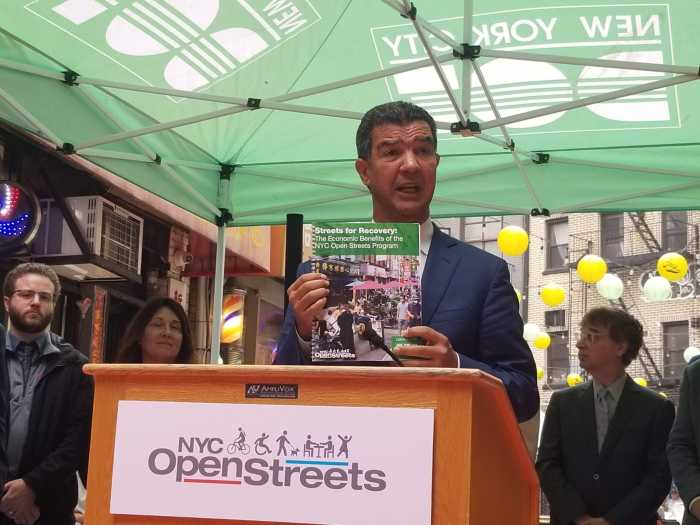

While the DOT declined to comment on this story due to pending litigation, agency officials have previously said Open Streets has benefits, including economic ones, for nearby businesses.

A 2022 DOT study, conducted with Bloomberg Philanthropies, found that during the first 18 months of the COVID-19 pandemic, restaurants and bars on Open Streets saw their sales grow by an average of 19% above pre-pandemic baseline levels, while those on “control corridors” saw a 29% dip in sales.

Open Streets are found in all five boroughs. Their hours of operation vary.

A City Hall spokesperson told amNewYork that the program has become a key component of NYC.

“Open Streets have become a vital component of the New York City landscape, giving New Yorkers better access to open spaces, providing small businesses with an economic boost, and creating a communal area for gatherings,” she said. “They also provide kids with a safe space to play outside, especially in neighborhoods where access to good parks is limited. For many New Yorkers — including our seniors and individuals with disabilities — Open Streets improves safety, enhances accessibility, and promotes greater equity.”

‘People can’t come and go through’ Open Streets

“What they actually do is use metal barriers or concrete blocks and obstructions to block the streets and the sidewalks in certain areas,” the plaintiffs’ lawyer, Matthew Berman, told amNewYork. “When those streets are blocked off, then you have a situation where there are no cars driving up and down the street, although the barricades have a sign that says ‘no thru traffic’ except for local traffic.”

Berman argued that disabled New Yorkers, or anyone with mobility issues, often have trouble lifting barriers to enter the zone.

“That’s really the issue,” he said. “People can’t come and go through these blocked-off streets.”

Volunteers with local civic groups typically manage open streets, some of which permit parking or deliveries. Barricades, such as steel barriers or cement blocks, are used to block off vehicular traffic, allowing room for pedestrians and cyclists, and in some cases, tables and chairs for relaxation.

“We don’t object to the fact that these spaces are being used for these purposes,” Berman said. “The issue is that our clients do not have equal access to the spaces because there is no way for them to get in and out.”

Berman noted that in other cities with similar open street programs, accommodations are made for disabled people.

“Other cities that have done stuff like this have installed retractable bollards,” Berman gave as an example. “Some cities have used metal ones where they can be pushed down into the ground, go passed them, and lift them back up again.”

Still, there are other options, Berman said, such as having volunteer attendants assist people in entering or leaving the open street.

“There are different kinds of solutions, but nobody wants to do anything,” he said. “They just want to have this program, and not think about what the impact is on the disabled.”

Some of Berman’s clients have trouble accessing paratransit and rideshare vehicles that cannot drive through a closed street. Generally, employers do not permit drivers to leave their vehicles, even if an Open Streets barrier has to be moved. Disabled customers are often forced to meet Access-A-Ride, paratransit and rideshare vehicles on the corners of open streets, according to NYC Access for All members.