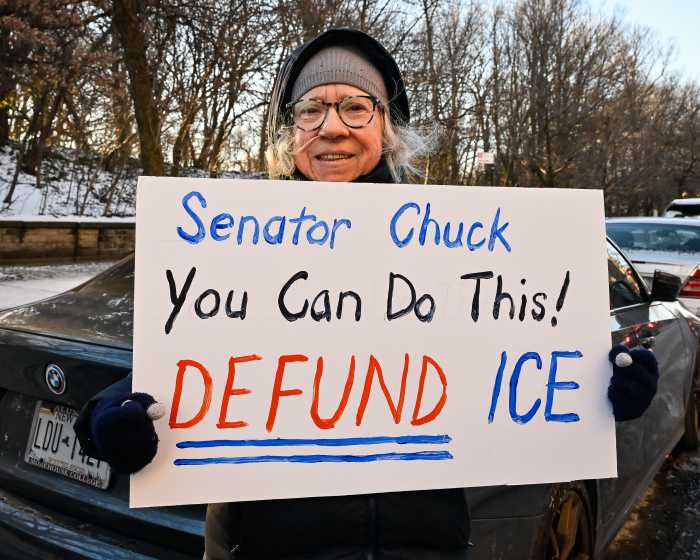

If you leave your trash out too early, fail to shovel after a snowstorm, or get cited for a noise complaint, you can end up with a ticket from the city. These are the kinds of low-level civil fines most New Yorkers run into at some point, and they’re supposed to be simple: break the rule, pay the price.

But here’s the problem: the price is the same no matter who you are. A $200 fine might completely upend one family’s budget, forcing them to choose between paying the city and paying the rent. For someone else, that same $200 is so small it barely registers. The result is a system that often fails at the one thing it’s supposed to do: change behavior.

That’s why we’re proposing something new. Our legislation would launch a pilot program to test a better approach: fines based on income, also known as “day fines.” The idea is simple: a fine should sting enough that you don’t want to break the rule again. If it’s too small to matter or too large to ever pay, it misses the point. Scaling fines to income keeps them meaningful for everyone.

This isn’t about punishing anyone or giving anyone a break. It’s about basic fairness and common sense.

Right now, New York City is owed more than $1 billion in unpaid fines and fees. That’s not because people are all scofflaws. It’s because many fines are simply unpayable for the people receiving them. And when people can’t pay, the city collects nothing, behavior doesn’t change, and trust in the system erodes.

On the other hand, when fines are too small to matter, people with means simply pay them and continue their previous behavior. Nobody wins.

Other countries have figured this out. In Germany, Sweden, and Finland, fines are routinely scaled to income — and compliance is higher as a result. In Finland, a wealthy driver once paid over $100,000 for speeding, not because the government wanted to “punish the rich,” but because that was what it took for the fine to have the same impact on someone earning far less.

Closer to home, San Francisco and Washington, DC have explored income-based fines for low-level offenses with promising results.

And this isn’t just theory; we’ve seen it work right here in New York already. A small-scale pilot in Staten Island tested income-adjusted sanitation fines and found that more people paid on time, and repeat violations went down. If it can work in Staten Island of all places, there’s every reason to believe it can work citywide.

Here’s how it could work in New York: through the Office of Administrative Trials and Hearings (OATH), the city would run a pilot program applying income-based fines to a range of low-level civil violations over the course of a year. We’d then study the results closely. Do more people pay their fines? Are repeat violations reduced? Does the city collect more of what it’s owed? If the answers are yes, we’ll have the evidence we need to consider expanding the approach.

Let’s be clear: this isn’t about serious crimes or criminal penalties. It’s about the everyday quality-of-life rules that keep our city clean, safe, and livable — things like sanitation, noise, and sidewalk safety. These fines aren’t meant to be revenue generators; they’re intended to change behavior and reduce the one million summonses issued last year. And if they’re not doing that, then we need to rethink how they work.

A system that adjusts fines based on income is better for everyone. It gives people a fair shot at paying what they owe, ensures penalties actually deter bad behavior, and helps the city collect money that’s currently sitting on the books. It treats New Yorkers not as numbers on a page but as people living in very different financial realities, while holding everyone to the same rules and standards.

At the end of the day, this isn’t a left or right issue. It’s a common-sense reform to a system that’s clearly broken. A $200 fine shouldn’t devastate one family while barely inconveniencing another. The consequence should fit the situation — not just the offense but the person’s ability to pay.

New York has always been a city that leads, and this pilot presents an opportunity to do so again. Let’s test a smarter, fairer system: one that actually changes behavior, improves compliance, and brings in the revenue the city is owed. Because when it comes to fines, one size really doesn’t fit all.

Justin Brannan and Lincoln Restler are City Council members representing Brooklyn.