When Aida Rodriguez came to NYC from Puerto Rico, she hoped to find temporary housing and a stable job. Leaving an abusive husband and the island’s collapsing economy, she fell in love with Jorge Senquis, who had also left Puerto Rico.

For months they talked about moving in together, but it would be difficult because Senquis lived in a supportive-housing single-occupancy unit that didn’t allow visitors.

Rodriguez ended up at a female city shelter in Brooklyn where, she says, workers derided her and other women for not speaking English. She asked for a transfer because her short stay was made miserable by restrictive curfews and back problems that made it painful to take the stairs. She was moved to a shelter in the Bronx, only to find out there were two flights up to her room — and no elevator.

Senquis, meanwhile, stayed in the Rockaways in a room so small he believed it had been half of a larger room. A nurse who was supposed to be there for residents, some on mental health medications, was not always at work, he says.

Kendall Jackman, a formerly homeless community organizer who now lives in city supportive housing, says the shelter and supportive-housing systems are broken. NYC now promises more units of supportive housing. This seems like a welcome change, but eventually, the answer has to be helping people support themselves.

“Supportive housing is not supportive, because if it was supportive you’d be able to get out,” Jackman says.

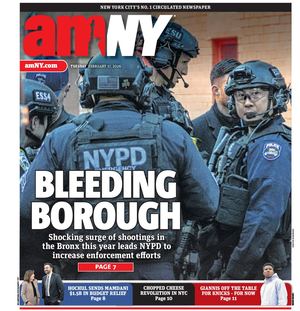

There is also the heavy hand of law enforcement in dealing with homeless New Yorkers. The Department of Homeless Services security force, dedicated to patrolling shelters, will now be trained by correction officers. This is the same corrections agency that was placed under a federal monitor for abuse of prisoners.

While the media often frame the homeless issue as a political football between the mayor and governor, the human toll we commit to an inhumane system is missed. We must reimagine how we treat homeless people. At best, it seems we’re content with warehousing our poorest people; at worst, we place them in informal prisons.

Josmar Trujillo is a trainer, writer and activist with the Coalition to End Broken Windows.