Diversity on the MTA Board got a boost Monday when Gov. Kathy Hochul inked a bill requiring to have a member with a disability going forward.

The bill signed into law requires one of the governor’s six appointees to the policymaking board of North America’s largest transit agency be a person whose disability requires them to use public transit. Nearly a million New York City residents are disabled in some form, and their experience on mass transit is vastly limited compared to non-disabled riders.

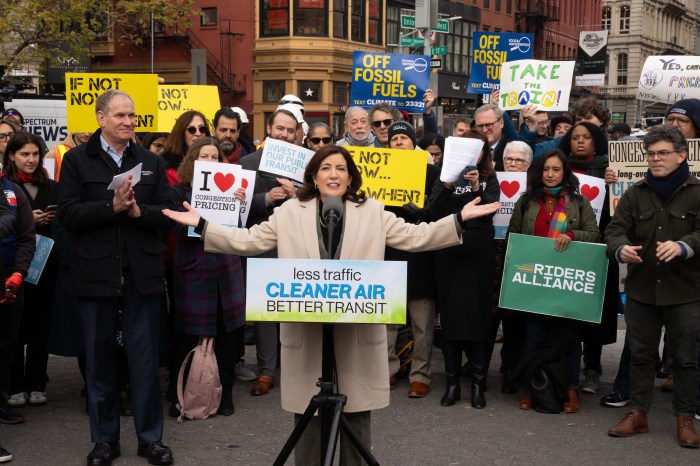

“For decades, the disability rights movement has said loud and clear: nothing about us without us,” Hochul said in a statement. “I’m committed to improving accessibility across the MTA’s network of buses, trains and subways. This new law will ensure the disability community has a voice and a seat at the table in deciding the future of transit in New York.”

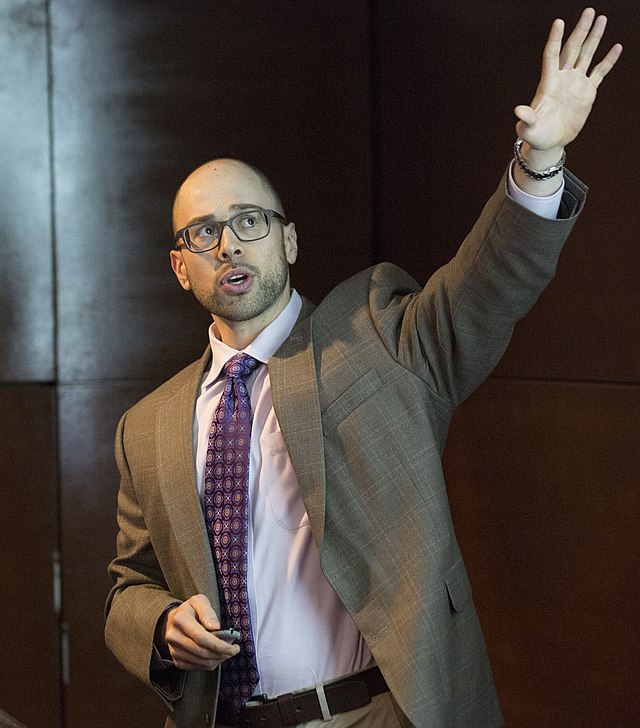

Even so, Hochul will not be naming a new member to the board to meet the mandate. In June, she appointed Dr. John-Ross Rizzo, a professor of rehabilitation medicine at New York University; since childhood, Rizzo has had a degenerative eye condition called choroideremia, which affects peripheral and night vision and ultimately causes blindness.

Before Rizzo’s appointment, the MTA hadn’t had a board member with a disability since the departure last year of Victor Calise, who also headed the Mayor’s Office for People with Disabilities under former Mayor Bill de Blasio.

Calise was the only member in the board’s history with a mobility disability that required him to access the subway via elevator.

The governor appoints six members to the MTA board, which is charged with voting on financial and policymaking matters for the transit agency controlling the subway, bus, commuter rail, and paratransit. The mayor of New York City appoints four members and the executives of Nassau, Suffolk, and Westchester counties each appoint one member, while Dutchess, Orange, Rockland, and Putnam counties are collectively represented by one member.

The board is nominally an independent body, but its budget and policy direction are predominantly controlled by the governor.

Playing catch-up on accessibility

The MTA is far behind other transit agencies in cities like Boston, San Francisco, and Washington D.C. in making its system accessible for people with disabilities. Just 29% of New York City Subway and Staten Island Railway stations are accessible via elevator, and much of the system is not compliant with the Americans With Disabilities Act passed more than three decades ago, requiring those with disabilities to go well out of their way to enter or exit the subway.

Wheelchair users are not the only people who navigate the subway with great difficulty. A lack of elevators is also a challenge for seniors and for people with strollers. Blind and vision-impaired people cannot read wayfinding signs and risk falling onto tracks without tactile warning strips on platforms, while hearing-impaired individuals are unable to listen to announcements in stations or aboard trains.

Last year, the MTA settled a pair of lawsuits brought by disability advocates and, in doing so, pledged that 95% of subway stations would be ADA-accessible by 2055. At that point, the ADA would be eligible for Medicare and Social Security if it were a person.

The MTA has committed a record $5 billion to accessibility upgrades in its current five-year capital plan, and pledges an even greater clip of investment in its next one as money flows in from congestion pricing. The agency also now has its first-ever Chief Accessibility Officer, Quemuel Arroyo, whose job entirely revolves around disability access.

But problems persist beyond the decades-long timeline for full accessibility. Disabled riders and advocates have long decried the MTA’s paratransit service, Access-a-Ride, as unreliable: riders have to book trips a day or more in advance, and only during regular business hours, and riders are often taken out of their way as vans pick up other passengers. The MTA touted a 90% on-time performance rate for Access-a-Ride in October, but considers “on-time” to be a pickup within 20 minutes of an appointment.

Last year, the Justice Department wrote a letter to the MTA accusing Access-a-Ride of being noncompliant with the ADA, by failing to provide comparable levels of service to disabled riders as those without disabilities who can ride the subway or bus unencumbered.

Meanwhile, advocates have pilloried the MTA over its proposed limits on Access-a-Ride’s e-hail program, which allows riders to request paratransit rides on-demand like an Uber. A limited pool of Access-a-Ride customers eligible for e-hail was expanded in August, but raised the price of a trip to $5 and capped the number of trips riders could take per month, after which they must pay market prices for a for-hire vehicle.

Disability advocates applauded Hochul’s signing of the bill into law. Shannon McLennon-Wier, executive director of the Center for the Independence of the Disabled in New York, said the move is “advancing equity on the Board of the nation’s largest transit system.”

“This action truly speaks volumes regarding diversity, equity, and inclusion for disabled people living in New York City,” she noted.

Read more: Runaway Carriage Horse Collapses on West Side Highway