Color is the first language we learn and the last one we forget. In Kre8’s universe, color is not an accessory to form; it is the emotional palette itself—the bloodstream of meaning.

He paints where pulse meets pigment, where the charge of the street collides with the hush of the studio, where a single incandescent idea (sometimes literally a light bulb) becomes doctrine: energy made visible.

Kre8’s chroma enters an old, exalted conversation and turns the volume up without losing the pitch. The Fauves—Matisse and Derain—first wrenched hue away from description and into feeling, teaching scarlet and viridian to speak in verbs rather than nouns. Chagall gave those colors memory; blues that could carry lovers, reds that could ring like church bells at midnight.

Add Kandinsky’s conviction that color acts on the soul, the Delaunays’ orbits, and Albers’ quiet proofs that every hue is a negotiator, and you begin to see Kre8’s inheritance.

He takes that lineage and routes it through asphalt and afterglow: blacks that read as architecture, neons that hum like marquee voltage. The result is a palette that doesn’t imitate life so much as electrify it.

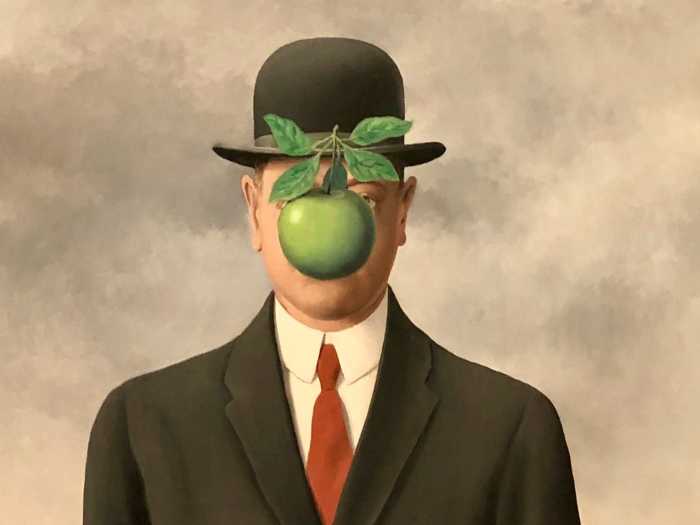

Then there is the dream engine. Kre8 borrows Surrealism’s right to let symbols breathe—Magritte’s plainspoken paradox, Dalí’s hyper-clarity—yet he swaps European irony for American propulsion. His icons (bulbs, ladders, hearts, mechanical forms flirting with flora) recur like motifs in jazz: return, vary, ascend. Surrealism becomes less a trick of perception and more a method of attention—lucidity with its eyes half-closed, a lucid dream that remembers it is awake.

The biography matters because it explains the line. Graffiti trained his hand to treat letters as bodies and space as choreography; tattoo taught him that every mark is irrevocable, every edge a promise. On canvas, those disciplines fuse into a confident structure that lets color misbehave beautifully. The “black-and-gray world,” as Kre8 calls it, is not vanquished; it is framed—a disciplined stage from which the riot of color can leap and still land clean. That tension—measured grayscale versus insurgent saturation—is the ethical core of his work. It says: the world imposes limits; the self refuses them.

Miami completes the argument. Wynwood’s chromatic weather—fluorescent pinks and yellows, aquas with aftertaste—gives Kre8 permission to let pigment act like climate. Against that backdrop, the light bulb stops being a cute emblem and becomes metaphysical: glass + filament + current = revelation. It is also an art-historical wink—Duchamp’s readymade stripped of coyness, Chagall’s floating lovers swapped for floating wattage—an insistence that ideas deserve hardware.

What makes the canvases compelling is not volume but control. The surfaces feel worked, not fussed; the drips know when to stop; the crescendo never clips. Kre8’s color is lyrical rather than loud, his blacks generous rather than punitive. If the Basquiat comparison is unavoidable (shared street DNA, fearless contour), Kre8’s orchestrations tilt toward harmony—chords held just long enough to change the air—where rupture would be the easier flex. He’s building rooms you want to live in, not just walls you want to photograph.

This is why the work is beautiful in the oldest sense of the word: it holds. It holds touch and tempo, biography and bravado, a century of chromatic scholarship, and the immediate pleasure of looking. It believes that illumination is communal—that if you wire artist, object, and viewer into the same circuit, everyone leaves brighter.

See the Charge in Person

Step into Park West Gallery in SoHo and stand close enough to feel the current—watch the grayscale frame the riot, let the bulbs hum at full volume, and let color do what it was always meant to do: influence the soul. Ask to view Kre8’s newest canvases; bring a friend who “doesn’t get contemporary art.” They’ll walk out carrying color.