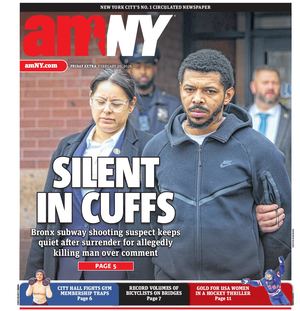

Silence is the first material; light is the second. In Man Ray’s rooms at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the hush has weight and the light thinks—slipping across paper, catching on glass, teaching objects to cast dreams instead of shadows.

When Objects Dream doesn’t announce itself so much as accumulate, ray by ray: a laboratory of stillness where innovation arrives without spectacle, and introspection—precise, surgical—turns the darkroom into a mind made visible.

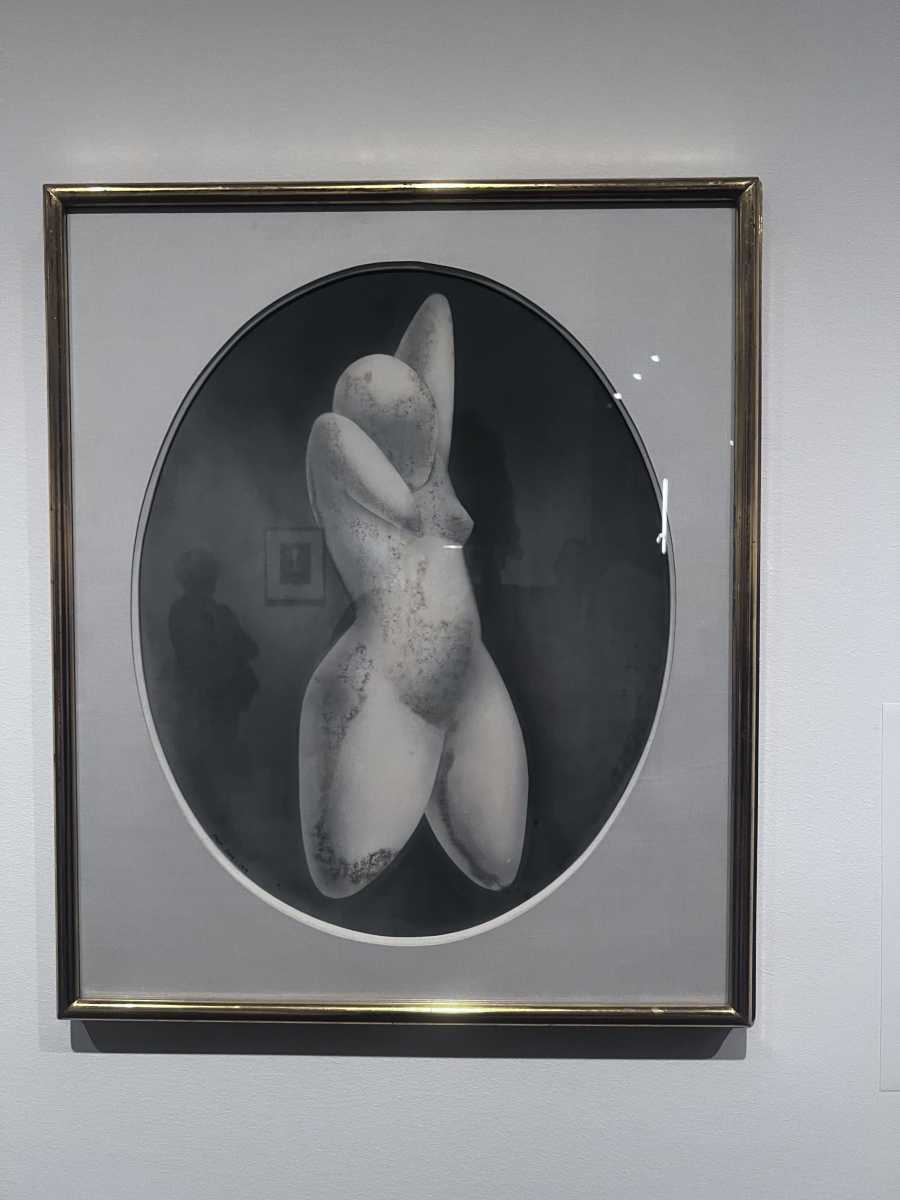

The rayograph—Man Ray’s cameraless image—turns eyesight into insight. Objects are placed directly on sensitized paper, exposed, and developed; the world reappears as a negative silhouette and luminous residue. Born in a Paris darkroom in the early 1920s, the method rebaptizes a 19th-century technique with avant-garde nerve.

Tristan Tzara’s exquisite line—pictures made in the moment “when objects dream”—is more than a slogan; it is a phenomenology. The Met’s curators take Man Ray at his word, exhibiting rayographs not as curiosities of process but as a nervous system threading everything else.

Origin stories are usually noisy; this one is quiet.

Man Ray later described an after-hours accident in 1921—glass labware on unexposed paper, a flash of light, an image “startlingly new and mysterious.” The tale has become legend, yet the exhibition uses it to mark a hinge: a turn from Dada’s unruliness toward Surrealism’s dream-logic, a period Louis Aragon once labeled the mouvement flou—blur as method, indeterminacy as rigor.

In that blur, Man Ray dissolved the boundaries most of us obey: between object and image, negative and positive, science and sorcery.

The show’s historical axis tightens around Les Champs délicieux (1922), a portfolio of 12 rayographs introduced to the public with Tzara’s imprimatur. The sequence reads like laboratory notes from a poet: pins become constellations, coils become weather, glass becomes grammar. It is a scholarship written in light. A century later, the work still looks strangely new, as if the paper were thinking for itself.

Cinema receives its due, and with it the Surrealist measure of time. Newly restored films—Retour à la raison (1923), Emak-Bakia (1926), L’étoile de mer (1928)—are screened in the galleries, revealing edits that feel like cuts in silk and flickers that register as incisions in perception. The moving image here is tactile; montage behaves like touch. The films make a simple argument elegantly: what Man Ray did to paper he also did to duration.

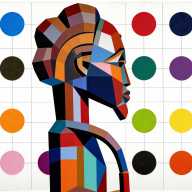

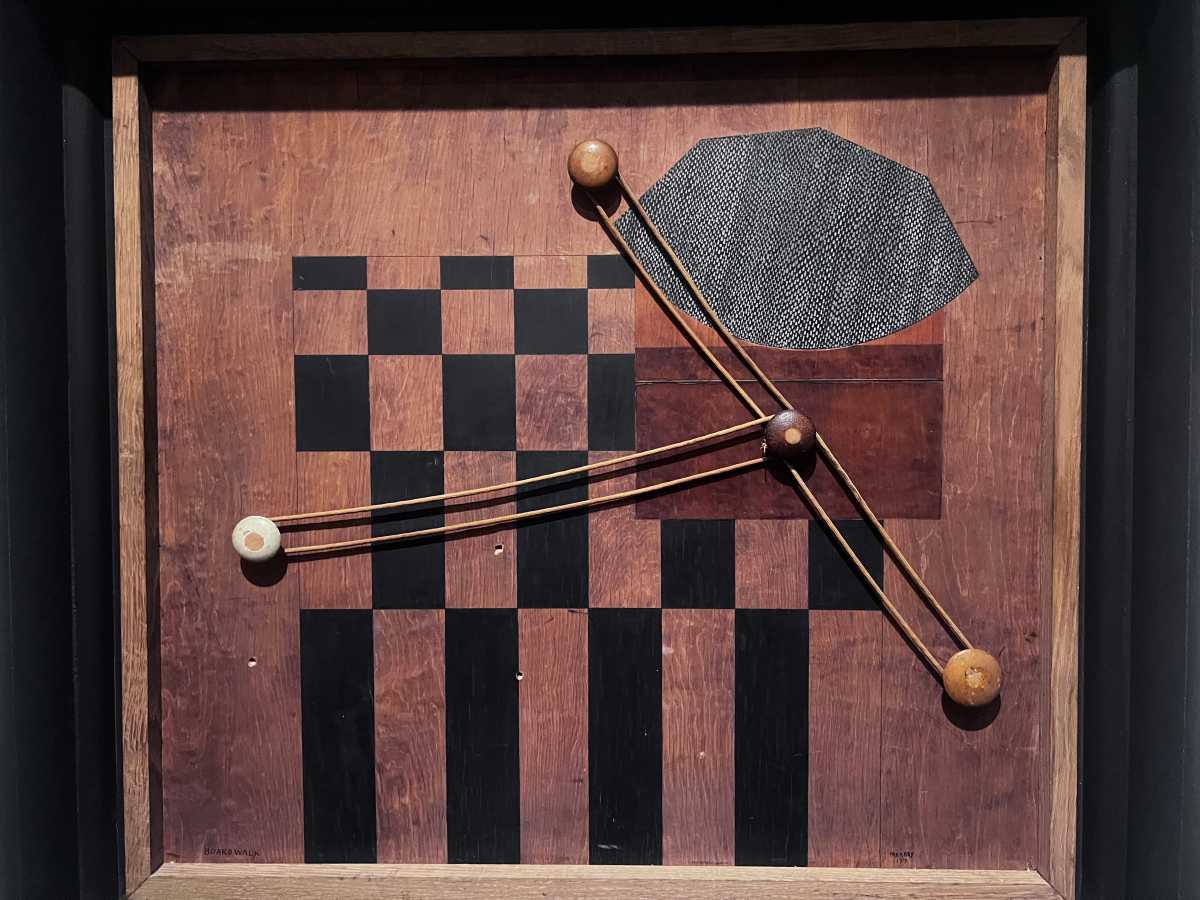

Across the rooms, icons from other media take the stage: the iron studded with tacks (Cadeau/Gift, 1921), the metronome with an eye for a pendulum (Object to be Destroyed, 1923), and the landmark photograph Le violon d’Ingres (1924). Nearby, a painting like Aerograph (1919) treats pigment as if it were light itself—sprayed through and around studio debris—while other canvases register the scraping, building, and re-building of a surface as if the darkroom had taught the brush a new grammar. This is not “multidisciplinary” for fashion’s sake; it is a single imagination manifesting across materials with unnerving precision.

The curatorial architecture is lucid. Works from more than 50 lenders are interleaved with The Met’s holdings, the rayographs gathered in a dramatic central presentation that radiates outward into painting, assemblage, photography, and film. The proportions are instructive—about 60 rayographs and around 100 works in other media—so the eye learns to read correspondences instead of categories. The room teaches you to see.

Provenance adds torque. The exhibition also marks a transformative promised gift of 188 Dada and Surrealist works from Trustee John A. Pritzker—the Bluff Collection—with thirty-five Man Ray works from that trove included here. Beyond sheer quantity, the gift finances a new research initiative, the Bluff Collaborative, whose programs fold live performance into scholarship (SQÜRL scoring Man Ray’s silent films; Trajal Harrell; an Alex Da Corte lecture-performance). The result is not simply a survey but infrastructure: a platform for future study, new restorations, and the next generation of questions.

Why this matters—now. Images are again up for debate: index and invention, truth and manipulation, machine vision and human attention. Man Ray reminds us that innovation can arrive as a still, exacting whisper. The rayograph is a model of disciplined wonder—empirical and dreamlike, radical and serene. In a world that confuses volume with value, When Objects Dream reads like a quiet thunderclap.

If you go…

Man Ray: When Objects Dream

Where: The Met Fifth Avenue, Gallery 199

When: September 14, 2025 – February 1, 2026

Access: Included with Museum admission; exhibition catalogue available at The Met Store. The exhibition is made possible by the Barrie A. and Deedee Wigmore Foundation, with additional support from major donors. Visit, stand close, and let paper, light, and shadow do their improbable work