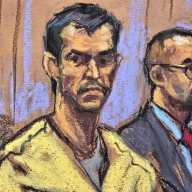

Matthew Marcot’s paintings do not aspire to contemporary ease or stylistic compliance. They operate instead as reminders of an older visual intelligence, one that understood images as charged sites rather than aesthetic objects.

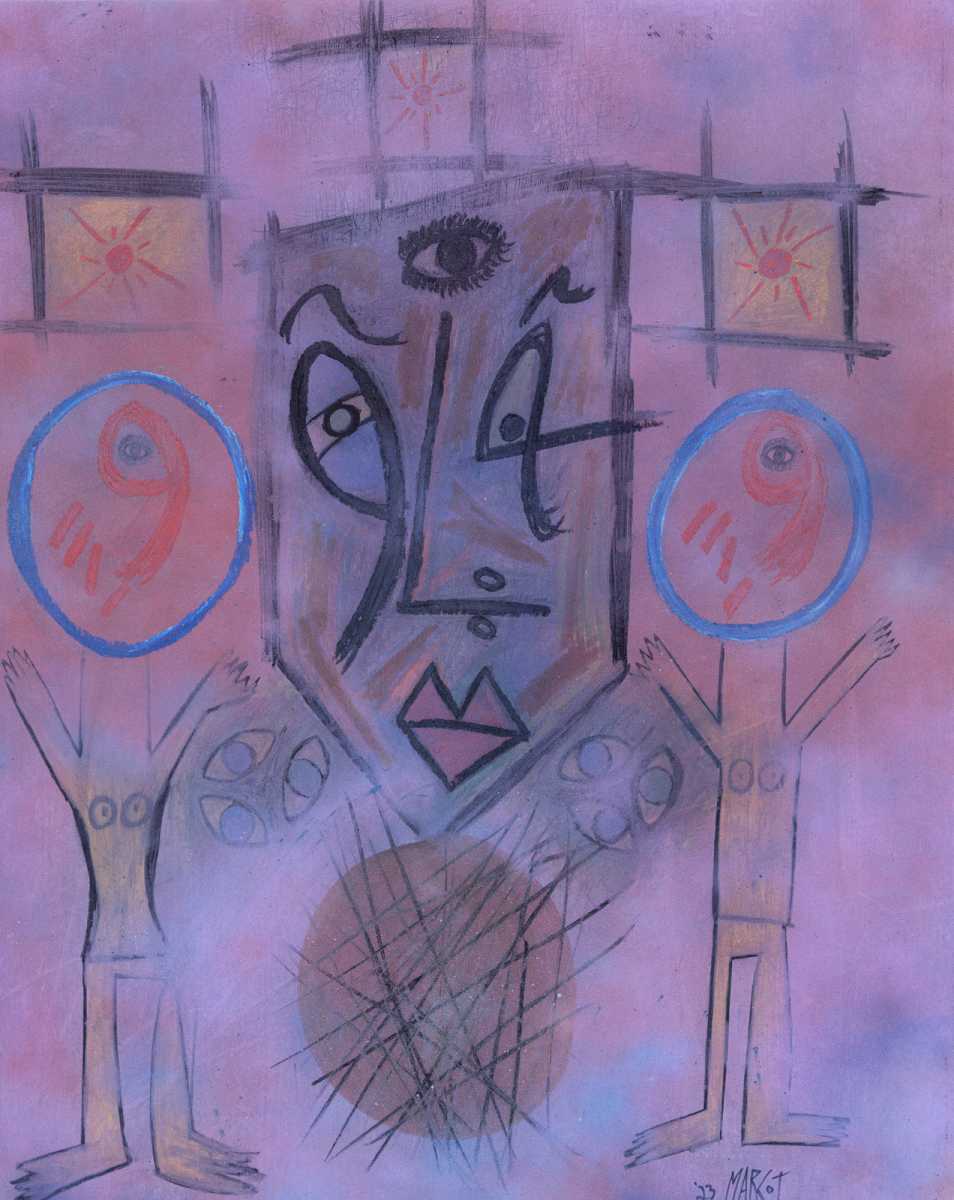

Faces in his work resemble masks pulled from ceremony rather than portraiture drawn from observation. Marks appear closer to glyphs than gestures, as though language itself were attempting to return to a pre-verbal state. Geometry enters not as design, but as containment, an effort to hold something volatile without neutralizing it.

Art predates language, commerce, and taste. Before museums codified value and critics supplied terminology, images were carved, pressed, and drawn as acts of necessity. Cave walls bore animals, hands, and signs not meant for admiration, but for invocation. These early marks were instruments of survival, belief, and orientation in a world that felt immense and unknowable. To make an image was to negotiate with unseen forces, to give form to fear, reverence, and longing.

That impulse—to mark in order to understand—has never disappeared. It threads its way through African sculptural traditions, illuminated religious manuscripts, and early modern abstraction, resurfacing whenever culture becomes too polished to remember its origins. Modernity did not erase ritual; it merely concealed it beneath refinement. Each generation that fractures convention tends, inevitably, to rediscover something ancient beneath the surface.

Marcot works within this uninterrupted continuum.

The conversation around Marcot’s work inevitably invokes Jean-Michel Basquiat, not as shorthand, but as lineage. Basquiat reintroduced urgency into painting by collapsing street, intellect, history, and spirit into a single visual field, insisting that a mark could still bruise, still provoke, still carry consequence.

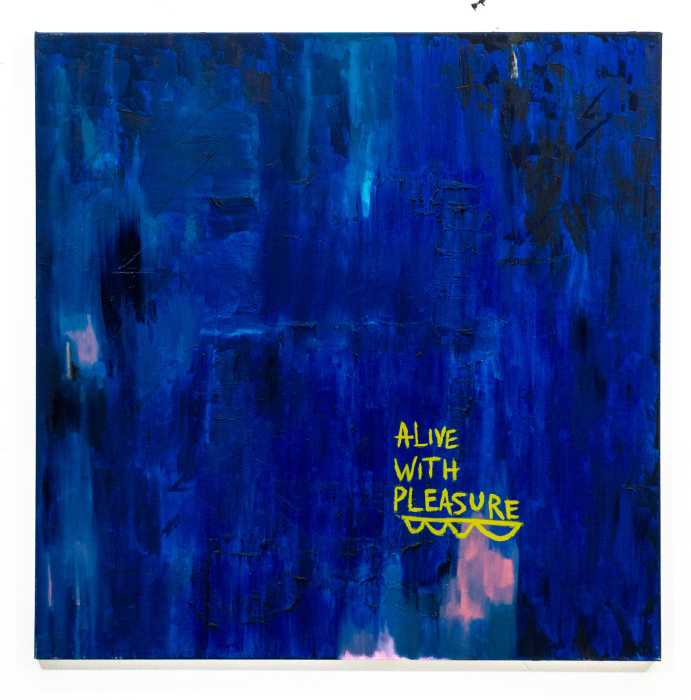

Marcot’s relationship to that legacy is philosophical rather than imitative. Rawness, in his hands, is not an absence of discipline but a refusal to dilute experience for comfort. The work does not seek polish. It seeks charge.

Born in 1997 and raised in Manhattan, Marcot emerged from a city that compresses perception early. Noise, signage, velocity, and bodies layered upon one another shape his visual awareness, yet his work resists the purely urban in favor of something more elemental. African sculptural logic, religious manuscripts, and the visual grammar of superstition surface repeatedly, not as references but as structural memory.

His hieroglyphic-like calligraphy reads less as invention than retrieval, as though symbols were being excavated rather than designed.

Material choice reinforces this sensibility. Charcoal, torn paper, scavenged objects, and acrylic applied with restraint form surfaces that retain evidence of prior life. These materials have histories before they enter the studio. In a culture increasingly defined by frictionless screens and seamless replication, Marcot insists on abrasion, density, and the trace of the hand. His work resists consumption. It demands encounter.

This orientation toward ritual is lived rather than theoretical. At twenty-two, Marcot stepped away from the art world to live briefly as a Hindu monk, immersing himself in a daily structure shaped by devotion, repetition, and ancient practice. The experience recalibrated his approach to making. What emerged was not iconography, but conviction: that art divorced from ceremony loses its gravity. Since that period, his work has carried the unmistakable feeling of offering rather than production.

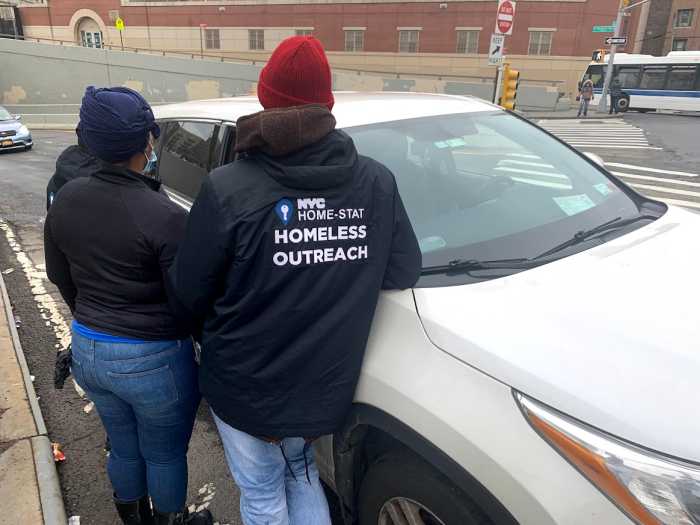

That intensity found public form during his years at One Sheridan Square, where Marcot transformed a rent-controlled penthouse living room into a studio and gathering space. Hundreds passed through. The output was relentless. The pace bordered on obsession. Visibility was not engineered; it was a byproduct of compulsion. By the end of 2022, this sustained momentum erupted into multiple solo exhibitions that marked a decisive arrival.

His recent exhibition, Primeval Uprising, clarifies the throughline. Returning to the methods that first defined him, Marcot collected discarded materials from the streets of Lower Manhattan and approached them through a shamanic lens. Masks emerged. Cave-like markings resurfaced. Symbols repeated until they felt activated rather than illustrative. The subsequent works on paper, Molana and Satori, move inward with quieter force, tracing what remains after prolonged immersion in primal states.

What distinguishes Marcot is not volume or ambition alone, but refusal. In a moment when contemporary art often prioritizes legibility, branding, and speed, he insists on friction, density, and discomfort. His work does not explain itself. It confronts. It reminds us that technological advancement has not replaced the human need for meaning, ritual, and symbolic exchange.

Matthew Marcot is not inventing a future aesthetic. He is reopening a channel that has always existed, running from the first marks pressed into stone to the present moment. His work suggests that art, at its most vital, is not about refinement, but about return.

Learn more about Marcot on Instagram @therealmarcot.