Surrealism—magical, disorienting, otherworldly—has always whispered like a forgotten spell across the fabric of time. René Magritte, that precise sorcerer, wove into the very DNA of the surreal its most primal, strange magic.

His paintings were not just images; they were portals, windows through which the ordinary became extraordinary, where the everyday could no longer be trusted. To gaze into Magritte’s work was to confront the sublime within the mundane. It was to see the world as though it had been conjured from the void, stitched together in ways both perfect and painfully illogical. The mystery was not hidden in what he painted—but rather in how he painted it.

The art world—tamed, grounded, and chiseled in realism—had never seen anything like it. Magritte approached painting like a high priest at an altar, reverently capturing the crisp, immaculate essence of things while simultaneously dismantling their very purpose.

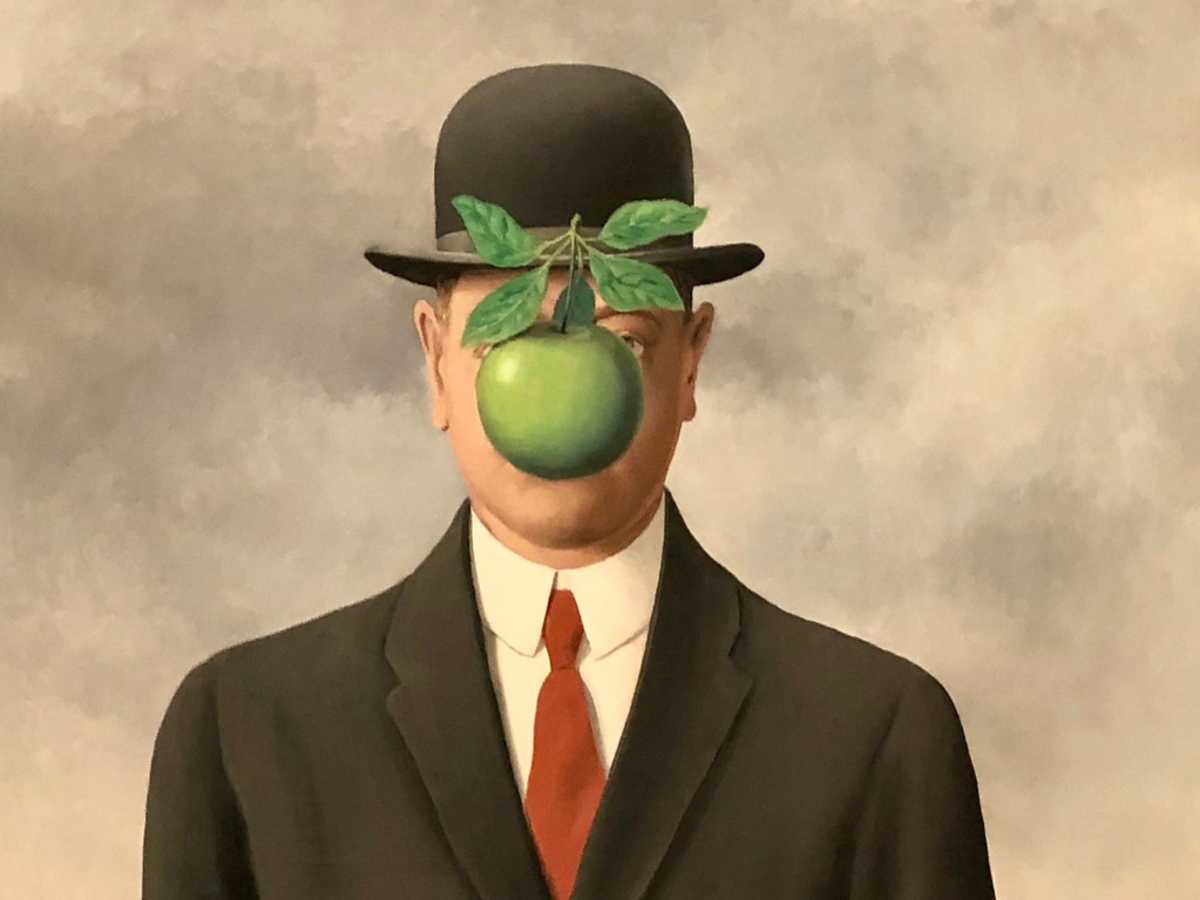

A bowler hat perched on a faceless figure, the mundane cigarette with its pipe-shaped universe, the floating apples and clouds that teased the boundary between what’s real and what’s a thought—each image was both a riddle and a revelation. His technical prowess was unmatched, his mastery of oil painting so meticulous that each surreal moment glimmered with the precision of cold, rational thought. Magritte was a mathematician of the unseen, calculating the exact angle at which perception would shatter.

This is where the alchemy happened—Magritte knew how to turn everything into a sign, a symbol, a question mark, and a key. He trapped the viewer in a world that made no sense, yet felt more like truth than any waking reality could. There, in that place between what’s tangible and what’s imagined, the soul could breathe freely.

Surrealism wasn’t just a movement; it was a map to the depths of consciousness. Magritte, with his poised palette, beckoned us to enter, to dare the labyrinth of thought, and see through the cracks in the illusion.

In today’s blinding, hyper-processed, digital storm, surrealism has not only endured—it has mutated. Magritte’s ghost still stalks the contemporary scene, flickering in the work of artists who dare to redefine what’s real in this age of filtered visions and artificial truths. The torch hasn’t just been passed; it’s been set ablaze in ways that resonate with this moment’s nightmare-fantasy combo.

Take, for instance, the work of Tina Modotti, who disrupts our sense of reality through her lens, as though she’s capturing something deeper, something rawer than mere life. Her still lifes are loaded with intention—fruits, flowers, industrial objects frozen in surreal composition. There’s no distance between object and emotion in her work. In the flicker of her photography, Modotti paints with shadows, using the sharp precision of technique to pull us into the void between thought and feeling. Much like Magritte, she makes us question: what do we really see, and what is the camera teaching us to believe?

Then we stumble upon Gregory Crewdson, the contemporary architect of suburban dreams gone wrong, whose cinematic tableaux haunt us with their perfect violence. Each image feels like an unsettling page torn from a dream diary, as if the surreal lurks in the corners of every neighborhood, waiting for the right moment to break through. Crewdson’s technical brilliance elevates the absurdity of his images—glossy, pristine, and yet always just a beat away from the uncanny. Here, as with Magritte, art refuses to be contained by the limits of physical space. He crafts the world of the dream like Magritte did—immaculate, precise, but laced with the darker things we never dare acknowledge.

Yayoi Kusama dives into a different yet deeply familiar kind of surrealism—she pulls us into a kaleidoscope of infinity, warping space until it’s so distorted it feels as if reality is falling apart. Polka dots are her language, her overwhelming symbol of endlessness. This, too, is an inheritance from Magritte: the transformation of the normal into something ethereal and infinitely expansive. Kusama plunges us into her world of dotty repetition, where the boundaries of space and self blur until we no longer know where the dots end and where we begin. In this universe, Magritte’s restraint and Kusama’s explosion both serve the same purpose—creating new spaces where we can no longer be passive observers.

In the dirty, noisy, gritty streets of urban life, Banksy emerges as the anarchist heir to Magritte’s surrealist tradition. His works are incendiary blasts in the otherwise sterile gallery world, popping up on walls as ephemeral as thoughts. Banksy’s use of public space as his canvas is his answer to the surrealist question: What if art weren’t confined to the gallery or museum, but poured directly into the streets, into the air we breathe? In his work, much like Magritte, the world seems absurd, chaotic, broken—but it’s also profoundly human. The technique—the cold, precise application of spray paint—doesn’t just subvert the expectations of realism, it forces us to look at the world with a sense of urgency and clarity that no longer feels possible in the post-modern haze.

Lorna Simpson — her work currently on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art—continues the torch with a muted fire of quiet surrealism, where fragmented collages of identity and race ripple across the surface of the canvas. Her technique—interwoven layers of photographic and graphic elements—invites us to peer into what has been silenced or erased, much like Magritte’s veiled figures invite us to question the unseen. What is concealed behind the surface? What does the body, in all its abstraction, try to tell us? Simpson’s layered works are a direct nod to Magritte’s enigmatic, haunting compositions: a visual language of illusion, of narrative fragments that refuse to cohere neatly, pulling us deeper into the whirlpool of interpretation.

In today’s world, Magritte’s surrealism is alive and breathing through these contemporary artists and their counterparts. But here, in the electric buzz of the 21st century, surrealism isn’t just a genre—it’s a condition.

The veil between the real and the unreal is thinner than ever, a fading line that digital technology, social media, and the 24/7 news cycle blur in maddening loops. The reality we consume is as fragmented, as constructed, as manipulated as a dream. We’re living in the surreal now.

Magritte’s precision and poetic subversion—the very act of twisting the everyday into a riddle—echo in the creations of today’s visionaries. In every fragmented truth, in every immaculate illusion, surrealism thrives, carving out its place in a world too disjointed to be fully grasped.

For more on the intersection of art, luxury, and surrealism, visit avalonashley.com—where the worlds of visionary artists and luxurious living converge in a kaleidoscope of possibility.