Wonderstruck

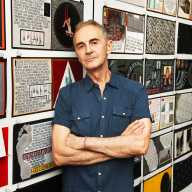

Directed by Todd Haynes

Starring Oakes Fegley, Julianne Moore, Michelle Williams, Millicent Simmonds

Rated PG

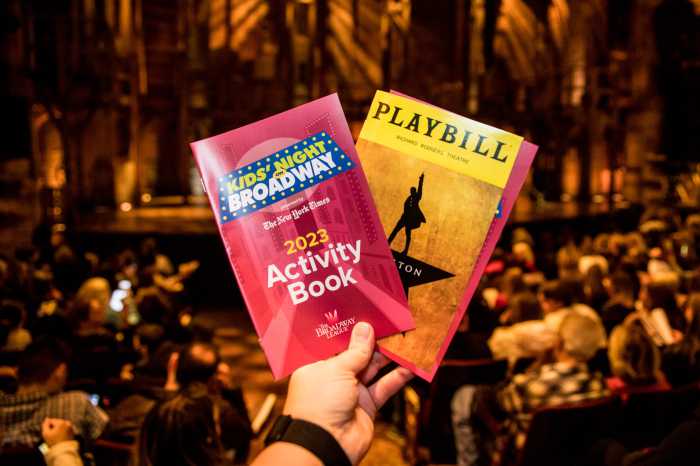

Playing at Angelika Film Center, Lincoln Plaza Cinemas

Todd Haynes is one of the best filmmakers around and constitutionally incapable of making a bad movie.

“Wonderstruck” is about as close as things get in that direction when it comes to the work of the man behind “I’m Not There,” “Carol” and other films that thrive thanks to a mastery of cinematic form and a knack for engaging storytelling.

That is to say it’s a New York City-set movie with pristine production values — its split structure finds the action taking place in a silent, black-and-white 1920s Manhattan stylized exactly like a movie from the final pre-talkie days as well as a gritty vision of the ’70s that feels familiar but authentic.

It’s the work of a filmmaker who understands how to convey the magical possibilities of this art form — the rich interplay of light and shadows, the metaphysical nature of the world of dreams and cosmic connections.

At the same time, when it comes to its storytelling, this adaptation of the 2011 Brian Selznick novel (Selznick, best known for “The Invention of Hugo Cabret,” also wrote the screenplay) violates basic principles.

It parallels the story of Rose (newcomer Millicent Simmonds), a New Jersey girl on a journey into the city circa 1927, with the quest of a Minnesota boy named Ben (Oakes Fegley) to find his long-lost father in the city 50 years later.

Ben has recently gone deaf after a lightning strike on his home (don’t ask) and he doesn’t know sign language. So the movie relies on an excessive number of scenes of characters writing things down and then reading them, which is about as dramatically inert as it gets.

That baffling choice exemplifies a storyline that drifts and meanders through a series of non-events, too often playing as space filler between the much better ’20s scenes, before arriving at a conclusion that anyone could have seen from miles away.

Haynes dresses things up with an abundance of Spielbergian flourishes but there is no compensating for the fundamental fact that half the story is utterly disposable.