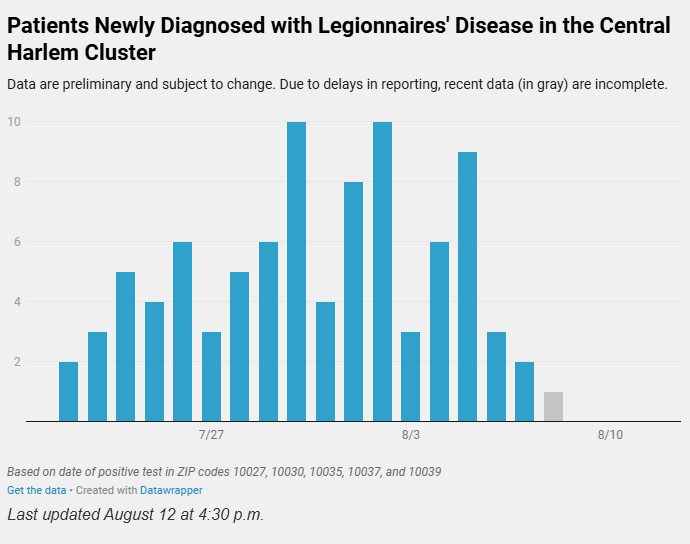

City health officials expressed confidence during a virtual town hall on Tuesday evening that the Legionnaires’ disease outbreak in Central Harlem, linked to 11 cooling towers, has been contained as confirmed cases continue to drop. But concerned residents pressed for more transparency from the department.

As of Aug. 12, the cluster had sickened 90 people, hospitalized 15, and killed three across five neighborhood ZIP codes.

Acting Health Commissioner Michelle Morse told Harlem residents on Aug. 12 that the number of new cases was on a downward trend, an indicator that the source of Legionella pneumophila, the bacteria that causes Legionnaires’ disease, was likely contained.

The Department of Health and Mental Hygiene launched an investigation on July 25 after a cluster of cases was reported across multiple buildings, leading officials to suspect a community-wide environmental source such as cooling towers.

“What’s happening right now in Central Harlem is that several people have been diagnosed with Legionnaires’ disease, but they’re not in a single building,” Morse said. “They’re in multiple different buildings. And that tells us that the spread of the Legionella bacteria is actually happening outdoors, not inside a building, but outdoors. And outdoors means it’s coming from a cooling tower.”

Of 115 towers tested in the outbreak zone, 11 showed preliminary positive results for Legionella through rapid PCR (polymerase chain reaction) screening and were ordered to undergo immediate biocide treatment. Officials said definitive culture testing, which confirms whether live bacteria are present, takes up to two weeks and remains underway.

According to city data, the highest concentration of cooling towers in the impacted ZIP codes is in 10027, which covers Central Harlem and Morningside Heights and has 57 towers, and 10035, which includes East Harlem and Randall’s Island and has 31 towers. ZIP code 10030 has seven towers, while 10037 and 10039 each have nine.

During the Zoom town hall, residents repeatedly asked officials to release the addresses of buildings with positive results. Health officials said they would not share locations while the investigation continues, but reassured residents there is no longer “continual exposure” in the area.

“With this Legionella cluster, there is a difference between the building and the community origin,” said Dr. Toni Eyssallenne, deputy chief medical officer. “When it is in the community, the localization piece is not as paramount in terms of the fact that everyone in that community, in that cluster, has been exposed, and the exposure already occurred.”

“I know people want to know addresses, and they want to get to the bottom of things. The first thing is that the entire investigation is still pending,” Eyssallenne said. “The second thing, the most important thing, is that walking down a particular street versus another is not going to change your exposure at this time.”

Eyssallenne said there should not be any persistent risk, “but we are continuing to surveil, and we are continuing to make sure that the numbers continue to go down.”

The Health Department’s website shares data of cooling tower inspections across the city, but there is a lag in updating those results.

Legionnaires’ disease is a type of pneumonia with symptoms similar to those of severe flu, including fever, cough, chills and muscle aches. The illness does not spread from person to person. People over 50, smokers and those with underlying health conditions such as diabetes or chronic lung disease are at higher risk.

Officials urged anyone feeling unwell to seek medical care immediately for rapid diagnosis and antibiotic treatment. While children and teens are considered low risk, officials said parents should still take them to a doctor if they develop symptoms, noting that an emergency room visit is the fastest way to get tested.

‘Canaries in the coal mine’

With some 6,085 cooling tower systems citywide, residents also questioned why outbreaks tend to occur in Black and Latino communities. NYC sees an average of 200-500 cases per year, according to the city health department, with the Attorney Generals Office finding that outbreaks are often concentrated in low-income areas.

“It’s not that Legionella discriminates; bugs don’t discriminate, they go where they have the best environment to flourish,” Eyssallenne said, acknowledging that disinvestment in these communities has played a role.

“This is something that’s structural. This is going back to structural racism,” she said. “There are structural reasons why there are a lot of people in a particular block, for example, which allows for exposure risk to be higher. So we’re talking about population density, we’re talking about how buildings are structured and built, and the systemic disinvestment.”

She added, “There is work for us to do,” and “we shouldn’t have this happen in black and brown communities.”

Gothamist reported last week that city inspections of cooling towers for Legionella dropped to near-record lows this year due to staffing shortages.

When asked about the reduced inspections, Corinne Schiff, deputy commissioner for environmental health, acknowledged the Health Department has staffing shortages, which “has led to a reduced number of inspections.”

New York State Sen. Cordell Cleare, who hosted the town hall and represents the area, said she suspects “there may be things that can’t be shared.”

“I just feel like a ball seems to have been dropped,” Cleare said. “We already know there’s even a Legionella season, and there’s a time and temperature at which this bacteria grows and becomes very active, and I just think every preventative measure should be taken.”

Cleare said that while the outbreak appears contained, the community deserves clear answers about its cause and prevention.

“I know you are still investigating and you’re still examining, but I can’t wait because I feel like we are the canaries in the coal mine, and it takes someone to get sick and sadly and unfortunately die to find out that maybe something wasn’t how it was supposed to be,” she said. “Whatever is in place doesn’t seem to be enough.”

On Aug. 6, Cleare introduced legislation requiring more frequent cooling tower testing, faster remediation timelines, higher fines for violations and improved tracking of repeat offenders.