BY HOWARD SCHNEIDER

A U.S. recession may already be underway. Could it be worse?

The Great Depression that began with a stock market crash in 1929 and lasted until 1933 scarred a generation with massive unemployment and plummeting economic output.

It reshaped America, shifting migration patterns, and spawning new styles of music, art and literature. Under President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, however, it also prompted creation of an array of programs like unemployment insurance, Social Security retirements benefits, and bank deposit insurance that make a repeat unlikely.

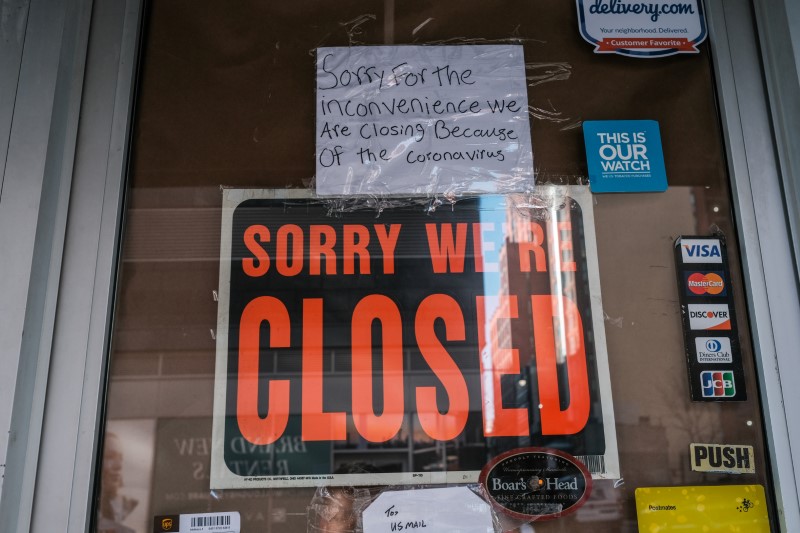

The unpredictable and unprecedented path of the coronavirus has drawn parallels with the Depression, in particular with predictions that the rise in unemployment and the percentage drop in economic output could rival those seen in the 1930s.

But for that to happen, the jawdropping numbers likely to be recorded in coming weeks – millions thrown out of work, double-digit declines in gross domestic product – would need to be both deep and sustained over years, not months.

“There is no specific definition of a depression,” said Bernard Baumohl, chief global economist of the Economic Outlook Group. But “it’s palpably different,” than a recession in terms of its length and depth.

In the Great Depression for example, the United States shed 20% of its jobs over three years, four times the share lost in the 2007 to 2009 Great Recession (https://tmsnrt.rs/2UA9wvX).

Over the four years of the Great Depression nearly a third of U.S. output disappeared. While some economists think U.S. annualized output in the April to June period may fall 14% or more, few think that type of decline will actually persist over time.

Government spending makes a difference. Unemployment claims have skyrocketed, but so has the amount of money the government plans to transfer to people and companies big and small.

These “stabilizers” have proved powerful in past downturns (https://tmsnrt.rs/39hoEnB).

Central banks matter too. Federal Reserve policy mistakes and failure to prevent a run of bank closures arguably contributed to the Great Depression.

This time, as in 2007, the Fed and global central banks have moved to soak the economy in cash and enact new programs to try to limit the risk of business failures and sustained unemployment.

The most important next step, a growing body of economists and policymakers say, is fixing America’s public health response. A haphazard patchwork of restrictions across states and a slow-to-mobilize White House could make coronavirus’ impacts worse, health experts say.

President Donald Trump’s push to “reopen” the economy quickly carries risks. Lifting lockdown restrictions too early could cause a second wave of the disease, according to a China-focused study published this week in the Lancet Public Health Journal.

The higher the toll of the virus, and the longer the outbreak lasts, the more damage to the economy.

“The first order of business will be to get the spread of the virus under control and then resume economic activity,” Fed chair Jerome Powell said on Thursday.