BY HESTER ABA

As parents, however we’ve personally been affected by the COVID pandemic, we are all suffering from some form of emotional burnout. We’re heading into an uncertain fall, with schools “reopening,” but plenty of stress and anxiety lying ahead, so we sat down for a chat with Dr. Marc Brackett, Director of the Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence and member of Mayor de Blasio’s 45 member Education Sector Advisory Council, for a check-in on how we can feel, understand and manage our emotions, and those of our children.

Dr. Brackett is also the author of Permission to Feel (which we recommend all NYC moms and dads grab a copy of) which features a system which has been adopted by schools across New York City, called RULER, a high-impact approach to understanding and mastering emotions.

Psst…Preparing for the new school year? Check out Our Ultimate Back-to-School Supplies Shopping List for 2020-2021: From Preschool to High School

How can we support our children’s emotional wellbeing during this pandemic, when we as parents might be struggling with our own?

If you have the mindset that you have to be the role model for my child, it changes your attitude about your feelings. Some people have a mindset that their anxiety makes them weak. Other people say, “My anxiety is an experience that I’m having. It may not be pleasant, but it doesn’t have to take over my entire life.” What I try to do is teach parents how to shift their relationship with their stress and anxiety, to give themselves the permission to experience the anxiety, without allowing the anxiety to have power over them.

We also experience feelings about our feelings: meta-feelings. I’m a father. I’m a mother. I can’t be anxious, that’s bad. And that’s not true. So, the first step is shifting your mindset about your anxiety. The second is labeling it properly. Because it may be anxiety. It may be stress. It may be that you’re overwhelmed. And each of those words has a different meaning. Anxiety is about uncertainty. Stress is about having too many demands on you, and not enough resources. When you’re overwhelmed, you just have so much on your plate and you just can’t function. On the surface, those things seem the same. But they’re not, because the strategies that we would use to help a parent manage overwhelmed, stressed, and anxious are different.

When we look at strategies for dealing with those emotions, the first is managing physiology. We’ve got to help parents deactivate, because with any of these emotions, if you’re driving yourself out of your mind with negative talk, like, “This is never going to end” and “I can’t take it anymore” and “What am I going to do about it that’s going to put you into a place of heightened arousal, which is going to make your brain go into fight or flight mode. If we can teach people how to deactivate through breathing exercises, or through taking a walk, or just giving yourself some space, then the brain becomes available for cognitive strategies that can be useful. Research also shows that you can distance yourself from your feelings by saying your name and then a phrase. So for example, “Mark, you can get through this.” Or “Mark, you’re stronger than you think.” Positive affirmations actually do help to shift thinking.

You can also engage in what’s called ‘reappraisal’ which is where you teach yourself how to tell a different story. If you have catastrophic thinking around COVID, you can say to yourself, “Let’s take a look at this from a different perspective. We’re doing everything we can to protect ourselves. We’re using masks. We are distancing. So the truth is we are pretty safe.” These are core strategies that parents need to use for themselves, and they also have to help teach their kids those strategies.

How much do you think it’s appropriate for parents to talk about our emotions surrounding COVID with our children?

It all depends on what your face looks like, what your body language looks like, what your vocal tone looks like, and how you demonstrate your ability to regulate the feeling. So if I walk into my house and say, “I can’t take it anymore. I’m going to freak out. Oh my goodness, everybody’s going to die,” your kids are going to be off the wall. The more you catastrophize, it’s contagious.

Negative emotions have a contagion effect. But if I walk in and say, “You know honey, daddy’s worried about the Coronavirus. A lot of people are sick and we want to make sure that we don’t get sick. And so we’re going to make sure that we distance from others. When we go outside, we’re going to wear our masks. And we’re going to have talks or conversations about it every night to make sure that we’re supporting each other, so that we can get through this together.” Totally different experience.

Is it helpful or unhelpful for parents to share when we are going through a difficult time emotionally, with their children?

Children are listening and children are watching. So if you don’t tell them, they’re going to know anyway. Research shows that sometimes the more you suppress the feeling, the more it shows up in your facial expressions in weird ways. So you don’t want to be a nervous mess and say, “No, daddy’s fine. Daddy’s fine.” They pick up on that quickly.

The most important thing is that when you’re communicating your feelings to your children, let them know that you are able to manage them effectively and that you’re not looking for them to take care of you. We want to normalize that life is filled with positive and negative emotions. Otherwise what we tell them is that when there’s a crisis we don’t talk about it. And so what kids grow up learning, is if they’re feeling fear and anxiety themselves, we suppress those feelings, which is the worst thing we can do for children’s healthy development.

How does a conversation sound where you’re introducing language around feelings and emotions with your children?

You’re at the dinner table, or you’re at breakfast, and you make it a ritual to just check in with everyone. So you’d say, “You know honey, daddy’s feeling pretty excited today. I’ve got this great meeting at work. I can’t wait to meet with this new client because I’m excited about this thing.” It’s about making sure that as a parent, you are showing your child that you experience all emotions. And then it becomes normal. Then there’s no taboo, there’s no fear, there’s no anxiety. And then you can ask them to describe how they’re feeling.

How will masks and online communication affect our efforts to understand the emotions of others?

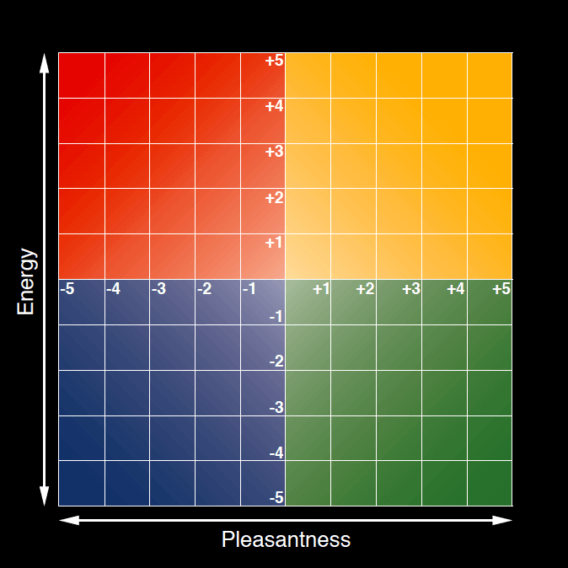

The only way to really know how someone is feeling is to ask them. So we have to create rituals around checking in with people, because certainly wearing masks is going to hide a lot of our ability to express. I mean the eyes are revealing, but not enough. We have a tool called the Mood Meter, which is in use at 400 New York City schools every day. The Mood Meter is a tool to say, “Hey, everybody, let’s just check in our feelings. What color are you in today? Yellow, red, blue, or green. All right, what’s your word?” And then the teacher can see the range of feelings that our kids are experiencing, then help kids. The same thing applies at home. You can say, “Hey honey, where are you today?” “Oh, daddy’s in the red.” “Why are you in the red daddy?”, “Well, because I’m really upset about this and XYZ. What about you?”

In schools, the Mood Meter is a poster board. We also have a virtual app for schools where teachers can put it onto Google classroom, or they can use our own platform. And kids can virtually check in, anonymously or with their names. Parents love the tool.

How can we teach our children the words for various feelings and emotions and the differences between them?

As part of RULER, we developed the Feeling Words Curriculum. The goal is to make sure children from preschool all the way up to their middle and high school years develop a full language to describe their inner experience. We teach preschoolers the basic words like happy, sad, calm and angry. For upper elementary and middle school, they learn words like alienation, apprehension, hopelessness.

The design of the Feeling Words program includes teachers and students sharing their own stories around feelings, and it can be linked to the curriculum. So kids can use it to analyze characters in social studies and in poetry. Then they go home and teach their parents the words. And so they’re having conversations with their families around feelings. And then finally, they get into conversations like, “Well, what do you do when you have these feelings?” If you do this every year of your academics, by the time you’re in high school, you’ve got hundreds of words and dozens of conversations around how to regulate, and we find that it really does impact children in a very positive way.

How will your work around RULER and emotions be pivoting to deal with these (groan) unprecedented times this school year?

So all the schools that have adopted RULER are going to go deeper with the work this year, of course. We have created amendments and extra strategies to support them through COVID, and also to help think through how to use Ruler to support more culturally responsive pedagogy, as well as to support difficult conversations around race. We want to make sure teachers understand there are possible implicit biases associated with reading children’s emotions, and to be engaging in deep reflection before they attribute an emotion to a child.

There is a bias associated with white people identifying Black people’s emotions. White individuals are more likely to attribute anger for example, to a neutral Black male’s facial expression. And so teaching people that that’s a possible bias is very important, because it’ll make people pause and reflect, and maybe ask the question before saying something like, “Why are you angry” or before even thinking that the person is angry, they’re going to second guess and say, “You know what, this may be my implicit bias operating here right now. I’m not going to assume this, I’m going to actually find out how the child is feeling.”

As an emotion scientist, have you been surprised by your own feelings during the COVID pandemic?

I would never have anticipated my own anxiety during this crisis. Here I am, supposedly an expert in this space, and I’ve struggled with my anxiety. And even a lot of my anger about what’s happening in the world. And so I’m working on it. I’m reflecting on it. I’m thinking about how I can appraise things in different ways to support my own health and wellbeing. I think if we think of this as life’s journey, we put less pressure on ourselves to be perfect at it right away.

As parents, we also just have to work at always trying to be the best possible role model for our kids. And when we mess up, we’ve got to be comfortable apologizing. And when our kids mess up, you’ve got to be comfortable forgiving. Otherwise there’s no room for error, and there’s a lot of error that’s going to be made in this work. And relationships have ups and downs. Let’s normalize the fact that everybody messes up, but that doesn’t mean that we have to dislike each other, or make each other feel bad. It’s a way to bond, by sharing that I feel bad about what I said and did.

What final words of advice would you like to share with New York parents at this time?

We want to give children permission to feel all emotions. And so that’s an important distinction versus trying to get them to not feel negative emotions and feel more positive emotions. With that said, we do want a greater balance of positive to negative emotions. So we don’t want to spend 70% of our day in that deep blue or high red, because that’s not good for our physical and mental health. We just don’t want to have a mindset that the negative emotions are bad. They’re signals. They’re information that we need to attend to and help people out.

And that means, secondly, that we really all need to strive to be, as I like to say, emotion scientists, as opposed to emotion judges. Curious explorers of our own and other people’s feelings, as opposed to critical judges who think we know how people feel. So by adopting what I call the emotion scientists’ mindset, we become open to our own and others’ feelings, and we become helpful in terms of thinking through options to manage our emotions.

For more insights from Dr. Marc Brackett, pick up Permission to Feel, out in paperback now, or visit moodmeterapp.com to download the Mood Meter app to use with your children at home. You can also listen to Dr. Brackett’s recent appearance on Brene Brown’s “Unlocked” podcast, which is a wonderfully enjoyable conversation.

This story first appeared on our sister publication newyorkfamily.com.