A new exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of art, called “Rayyane Tabet/Alien Property,” tells the story of how ancient reliefs from Syria ended up in New York City — and the story’s personal connection to one artist and his family.

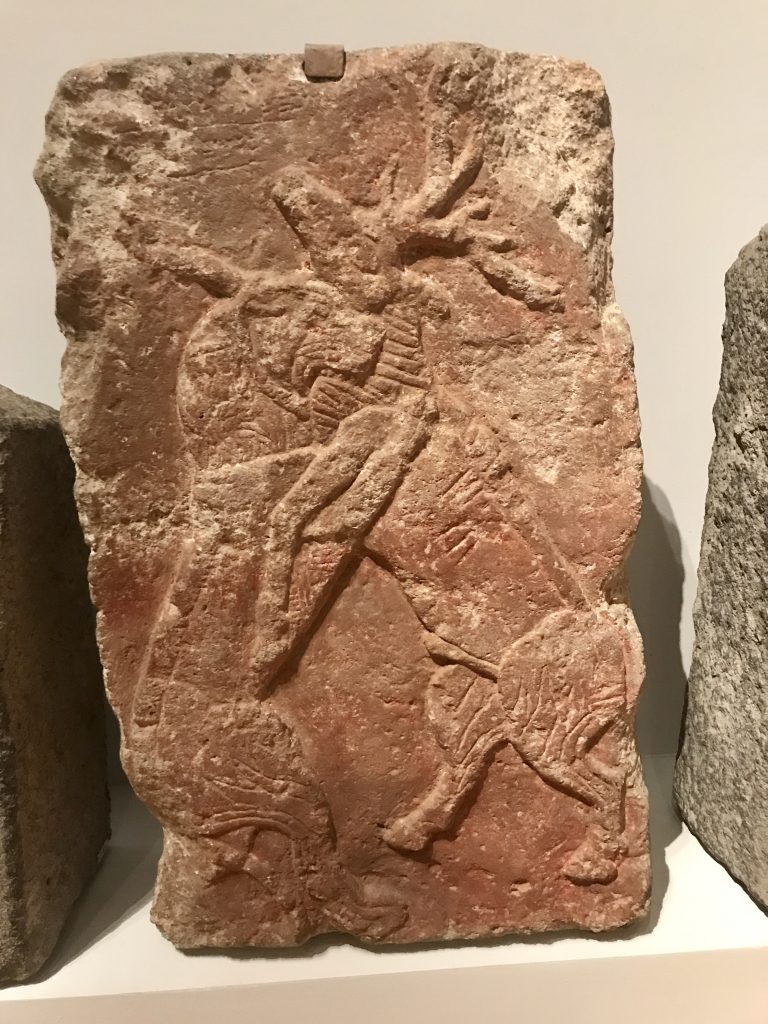

During a 1911 excavation at Tell Halaf, in current-day Northern Syria, Baron Max von Oppenheim, a German diplomat and amateur archaeologist, discovered 194 stone slabs with relief carvings. The slabs, also called orthostats, were along the base of a Neo-Hittite palace and dated back to the 9th or 10th century B.C.E. Some depicted mythological scenes, while others featured animals or scenes from everyday life like hunting.

It can sometimes be uncomfortable to think about the ways that artifacts end up in museums, especially when they originate from different cultures and regions of the world. But this exhibit dives into all the details, including when authorities in 1929, under the French Mandate for Syria and Lebanon, divided up and allocated the relics found in Tell Halaf.

As the excavation director, von Oppenheim received most of the finds, including about 80 of the stone slabs. In 1931, he traveled to the U.S. with eight of the slabs in the hopes of selling them. He was unsuccessful and left them in storage in New York.

Then in 1943, American authorities seized the stored stone slabs through the Office of Alien Property Custodian, which had been reactivated for World War II. Shortly after that, the Met bought them from the agency at an auction. The Met sold four of the eight slabs to the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, and the other four have remained with the Met ever since.

The other side to the exhibit is the personal connection of Lebanese artist Rayyane Tabet, 36, who discovered a family connection to the artifacts. Tabet’s great-grandfather, Faik Borkhoche, was a schoolteacher and translator who was assigned in 1929 by French authorities to be von Oppenheim’s secretary. However, he was also given a spy mission to gather information about von Oppenheim and the excavation at Tell Halaf.

Borkhoche would be at the excavation site for six months and stay in touch for years afterward with von Oppenheim. The German even gifted to Borkhoche in 1932 a book he wrote about the Tell Halaf excavation.

The exhibit includes the Met’s four ancient stone slabs with mythological carvings, and also works by Tabet that were an attempt to unify the slabs that are now scattered in museums throughout the world. Tabet made charcoal rubbings of the reliefs, 32 in all, that include slabs from Berlin, New York, Paris, Baltimore, Aleppo and London. There are also personal items from von Oppenheim and Borkhoche on display, related to the excavation in Tell Halam.

“We live in times of transition and uncertainty,” noted Tabet in a statement about the exhibit. “Working on this show has solidified my belief that we have to confront our past head-on in order to ground ourselves firmly in the present, and through the process begin to imagine what might be possible.”

The exhibit is an interesting combination of ancient artifacts and the story and context of how they came to belong to institutions on the other side of the world. It would be a valuable trend for museums, when possible, to be transparent about items’ full journeys that eventually led to the museum, even when a darker element like colonialism is at the heart of the story.

The “Alien Property” exhibit will be at the Met until Jan. 18, 2021.