BY DUSICA SUE MALESEVIC |As the city grapples with protecting its coastlines two years after Superstorm Sandy hit Oct. 29, 2012, it is moving forward with the “Big U” design to safeguard parts of the Lower East Side, while there remains a lack of funding for other vulnerable sections of Lower Manhattan.

The first section that does have $335 million in funding stretches from Montgomery St. to E. 23rd St., but does not cover several public housing projects in the Lower East Side such as LaGuardia, Knickerbocker, Rutgers and the Smith Houses, or any neighborhoods to the south.

“I’m not happy,” Aixa Torres, president of the tenant association at Alfred E. Smith Houses, said in a phone interview. “The hardest hit are the ones that will be the least protected. What happens to the rest of us?”

During Sandy, Smith Houses did not have power or water and experienced flooding.

The Montgomery boundary does include the Vladeck Houses, and Nancy Ortiz, president of the resident association, is happy about that, but not that other complexes will not be covered.

“It’s very disheartening other areas that should have been included were not,” Ortiz, who along with Torres participated in community Big U meetings and workshops, said in a phone interview. “We were under the impression it was going to cover past the Smith Houses.”

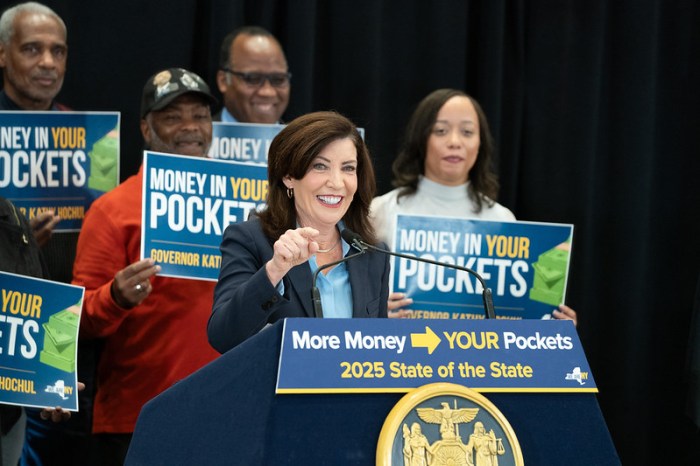

Downtown Express file photo by Aline Reynolds

In June of 2013, the U.S. Dept. of Housing and Urban Development launched the Rebuild by Design contest, which was a “multi-stage design competition to develop innovative, implementable proposals that promote resilience in the Sandy-affected region,” according to its website.

Sandy was the second most expensive natural disaster in the country’s history, according to the website. One of the ten teams was BIG, the Bjarke Ingels Group, a design and architecture firm that has offices in Denmark, New York City and China. (The BIG team also worked with partners.)

The team proposed the Big U, a series of protective measures such as berms that were envisioned stretching from W. 57th St. south down to the Battery and then up to E. 42nd St., creating a “U” around Manhattan.

The BIG team divided Lower Manhattan into what they term compartments. The first compartment, C1, runs from E. 23rd St. to Montgomery. The second compartment, C2, is from Montgomery St. to the Brooklyn Bridge. The third, C3, is from the Brooklyn Bridge to the Battery.

HUD awarded $335 million for the first compartment out of $930 million total for the winning proposals. In deciding which section to fund, HUD worked with the BIG team and decided on the stretch from Montgomery to E. 23rd St., said Holly M. Leicht, HUD’s Regional Administrator for New York and New Jersey.

Part of that analysis included how the tidal surge would affect the area, the vulnerability of the area, and that it was a low-income neighborhood with public housing, she said in a phone interview.

HUD worked with the teams so that each phase of a proposal would be a stand-alone project, said Leicht.

“It wasn’t realistic to fund all the phases for all the projects,” she said. “But we wanted to ensure that we got the ball rolling for many of the deserving projects as possible.”

Leicht said that the next two sections would not by funded by HUD, although there is some funding available from the National Disaster Resilience Competition, which is somewhat similar to Rebuild by Design, but is for all areas affected by disasters between 2011 and 2013.

For the BIG team, the focus on the first compartment was that it protected “a deep floodplain next to the F.D.R. Drive, which separates it from East River Park. The park, now badly connected to the community, has room for a protective berm,” according to Daria Pahhota, a BIG spokesperson, in an email.

“There’s about 620 acres being protected there, about 130,000 people, 86,000 of whom are low income, elderly, or disabled,” Pahhota said. “So, in terms of risk, both in the future and also as was demonstrated during Sandy, it made a lot of sense as a place to start.”

The team did a cost estimate for the three compartments. Each could cost between $300 and $500 million, with a total of about $1.2 billion for all, which would protect four and half miles of coastline from the Battery to E. 23rd St., according to BIG. If completed, the entire project would cover ten miles of Manhattan. There is no estimate of what the total project would cost, Pahhota said.

“It was not clear to us that it was strictly going to be the compartment from Montgomery to 23rd,” Damaris Reyes, executive director of the Good Old Lower East Side said Oct. 21 at a Community Board 3 committee meeting. “The community, I think, was under the impression that the compartments were smaller … and that it could be any sort of combinations of stretches of land.”

She and her organization, GOLES, worked hard to connect with residents to attend Rebuild by Design meetings and workshops. Reyes said at the meeting that her entire staff dropped everything to focus on it.

“We’re not in a position to do that again in the future,” said Reyes.

Daniel Zarrilli, director of the Mayor’s Office of Recovery and Resiliency, gave a presentation about the Big U at C.B. 3’s Parks, Recreation, Cultural Affairs, Landmarks & Waterfront Committee Oct. 21.

“We want to make sure we’re directing limited dollars towards the areas of the highest risks,” he said. “The Lower East Side comes up as very high in that analysis.”

There are a large number of people who live in the floodplain, explained Zarrilli, and that coupled with a density of critical infrastructure of public housing has made it a high priority for flood protection.

As of now, the concept is a series of levies and bridges that would keep most of the East River Park open to the community.

“In many ways we are at step one on this project,” he said. “We have a lot of work to do. There are a lot of decisions to be made.”

The city has assembled a large team to facilitate the project, which will include the Dept. of Design and Construction, the Parks Dept., and the Mayor’s Office of Recovery and Resiliency.

“HUD awarded the money, $335 million, what they don’t do is show up with a sack of money and say, ‘have fun, go build stuff,’ ” he said.

There is a bit of bureaucratic process, said Zarrilli. HUD had just released recently what it calls the notice. The city has to write an action plan that details how it will spend the money, which will go out for public review and comment. There will be public hearings, the city will solicit public comment via its website, people can call 311 or write letters. Once the final plan is submitted to HUD, it has 60 days to approve it.

This may be completed by next March. Currently, there are surveyors walking up and down the East River Park to gather baseline conditions. The city will also put out an R.F.P., which stands for request for proposals, for preliminary design consultants and community engagement services.

“We have a very aggressive goal, we want to see groundbreaking in 2017,” he said.

Zarrilli also fielded questions about why other areas, such as Two Bridges, would not be covered by the Montgomery section.

“We’re certainly aware of the risks in Two Bridges as well further down to Lower Manhattan,” he said, but there aren’t funds yet for construction.

“Honestly, it may end up being very difficult to make $335 million work simply within the boundaries that we’re talking about it,” said Zarrilli. “It’s important to recognize, it sounds like a lot of money until you get into a big multi-layered construction project.”

Councilmember Margaret Chin said in an email statement that she was “extremely pleased” when the Big U plan’s first phase— which only covers part of her district — was awarded $335 million in federal funding this year.

“I believe this project will become an important part of our long-term approach to waterfront resiliency, and I will certainly continue to advocate for the Big U to become fully funded, so it can eventually help to protect all of our Lower Manhattan neighborhoods from future storms,” Chin said in her statement Oct. 27. “I also look forward to working with both the mayor’s office and the community to make sure local residents’ voices are being heard throughout this process.”

The lack of funding for the third compartment from Brooklyn Bridge to the Battery has become a priority for Community Board 1, which passed a resolution in June urging HUD for funding.

“We need the city, state and federal government to come together and work on parallel tracks to design, to fund and to build the Big U in C.B. 1 and to address the root causes of extreme violent climate events like Sandy that cost lives and caused significant damage,” Catherine McVay Hughes, chairperson for C.B. 1, wrote in an email last month.

Curtis Cravens, from the Mayor’s Office of Recovery and Resiliency, said at an Oct. 6 C.B. 1 Planning Committee meeting, that the city is “hopeful that we’re going find that funding.”

“This community’s on the record for supporting the Big U. What kind of timeframe can we see something really happening down here,” Hughes said at the meeting. “Because two people drowned in C.B.1.”

That question, and the question of funding, is still unanswered.

C.B. 1 should have funding for a proposed project for a part that would complement the Big U — $2 million toward a berm and deployable walls for Battery Park, which was part of the NY Rising Community Reconstruction Plan, a report that was released in March 2013.

NY Rising gave local communities affected by Sandy the opportunity to plan projects that would strengthen resiliency in their neighborhoods. The Lower Manhattan community has been allocated $25 million through HUD, said Alex Zablocki of the Governor’s Office of Storm Recovery, at the meeting.

“It’s already designed conceptually and this funding would advance that further and build a berm from just north of Whitehall Terminal into the park and prevent storm surge into Lower Manhattan,” said Zablocki.

Marco Pasanella, a member of C.B. 1 and the Old Seaport Alliance, said he is hopeful about the Big U, but worried about the lack of immediate and short-term measures for the Seaport — such as rapidly deployable flood barriers.

“Arguably the most vulnerable part of Manhattan remains defenseless,” he said, referring to the historic neighborhood that Sandy hit hard.

“We’ve not made the progress I’ve hoped for,” said Pasanella. “We are exactly where we were the day before Sandy.”