More than 500 former residents, relatives, people with disabilities, advocates, officials and others marked the 50th anniversary of the signing of a document that led to the closure of the infamous Willowbrook State School and ushered in a new era.

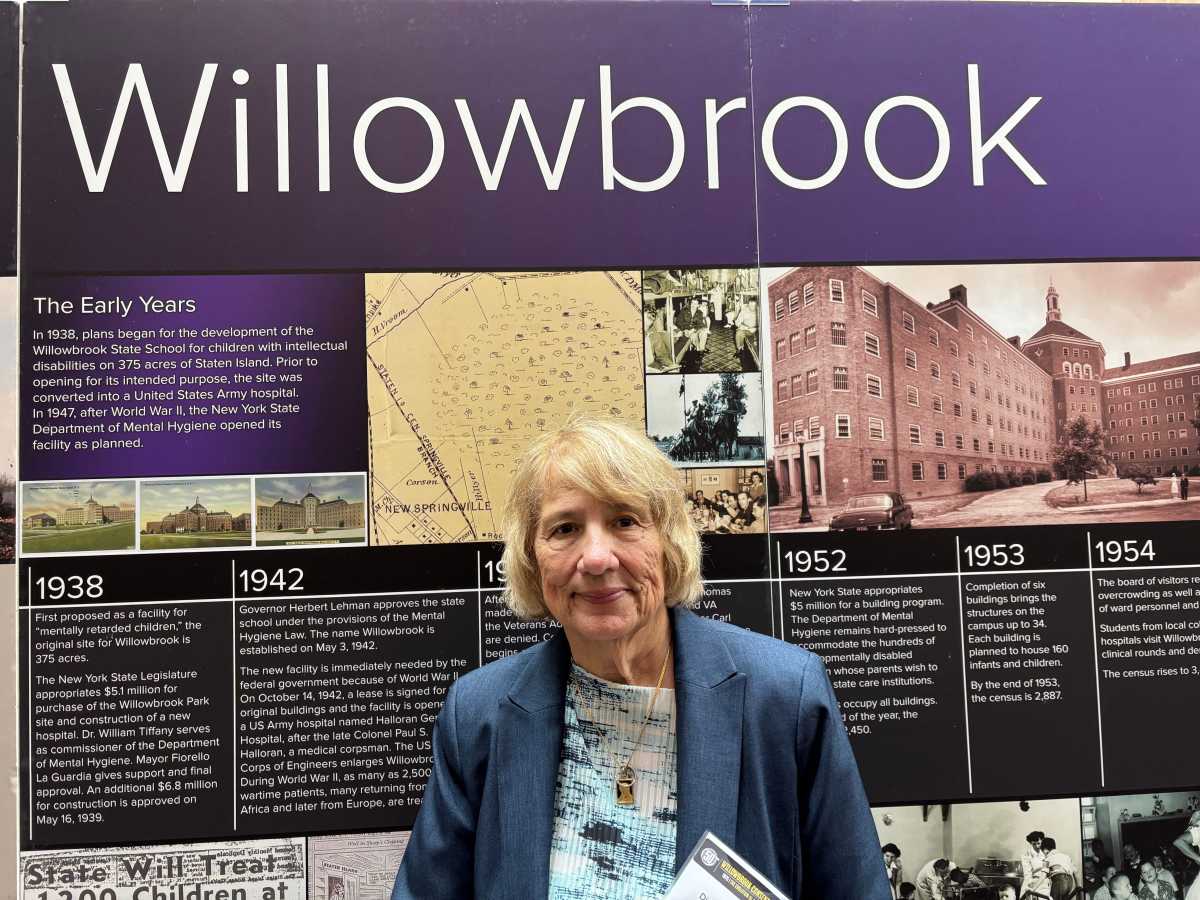

They gathered on Friday, May 2 at the College of Staten Island — built on the grounds where Willowbrook once stood — to describe not only how Willowbrook became emblematic of an era when people with developmental disabilities were warehoused, but also the events that led to the institution’s end.

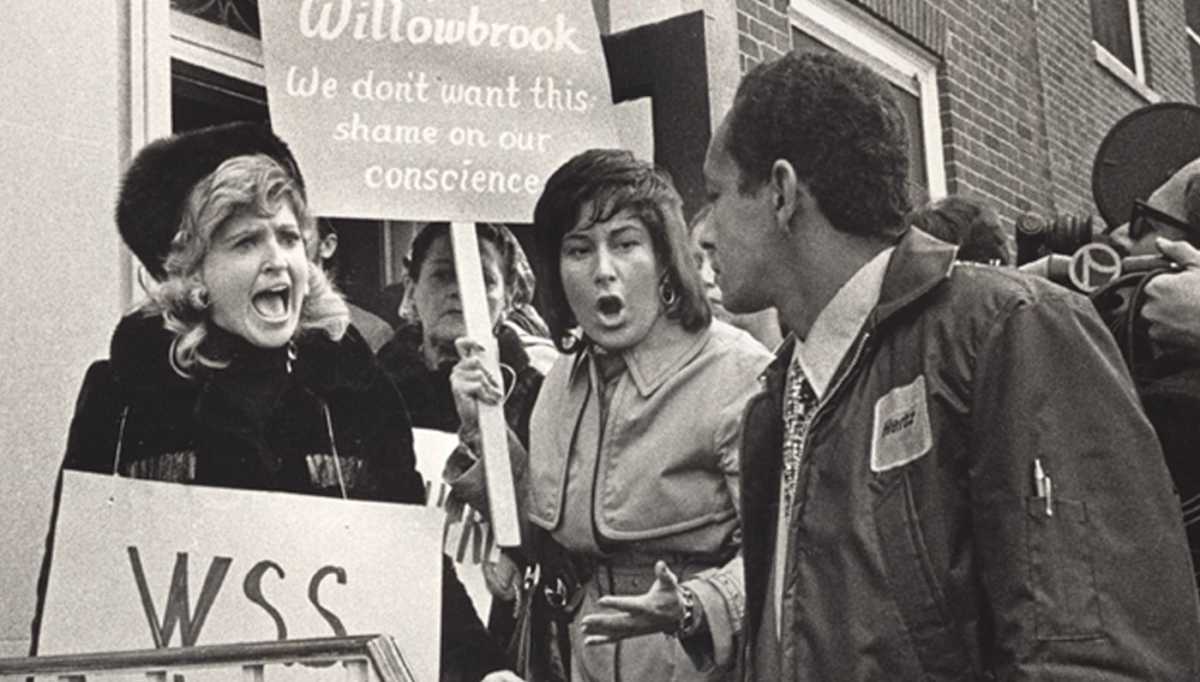

They talked about a journey from institutionalization to inclusion and the horror of seeing images of naked, neglected patients on floors, curled up beneath sinks and otherwise forgotten until intrepid journalists shined a spotlight on a shameful chapter in the state’s history.

Those gathered at the May 2 event also spoke of the need for continued vigilance amid possible cuts to services for the disabled, but also as much about progress as the pain that preceded it.

Someone in the audience shouted, “Never go back,” which seemed like a rallying cry among those fighting to move forward and not forget.

Willowbrook closure ‘a landmark moment’

Just as Stonewall became a rallying point for LGBTQ+ rights in America, they said the battle to close Willowbrook helped champion the rights of developmentally disabled Americans and transition care from large, neglectful settings to smaller, intimate group homes where people could get the direct, individual attention they needed.

Timothy Lynch, president of the College of Staten Island, called Willowbrook’s end “a landmark moment in our nation’s history and a pivotal turning point in the fight for rights and dignity for in the life of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities.”

In 1993, the College of Staten Island acquired 204 acres of what had been Willowbrook and built a great campus where students now study and play sports.

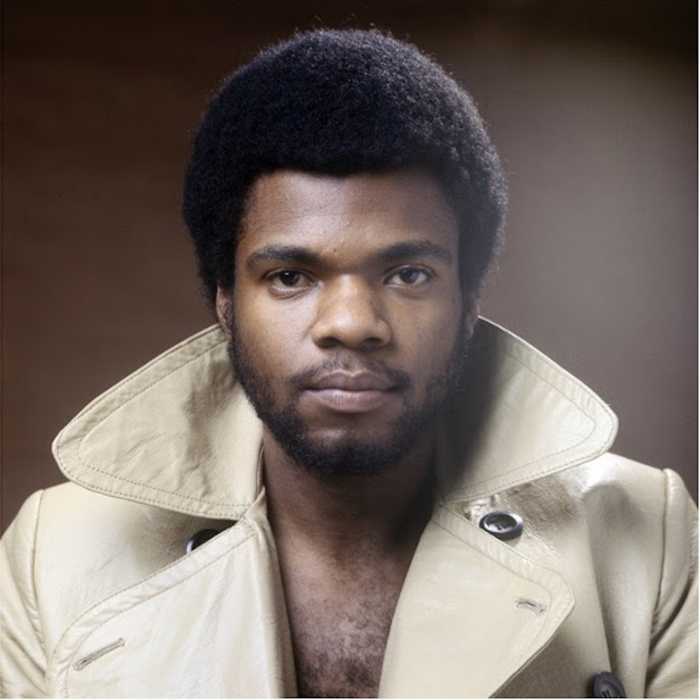

Many argue that the post-Willowbrook era would not have come about without the reporting of Geraldo Rivera, a WABC-TV reporter who helped expose the conditions at Willowbrook to millions of people at the time.

“This existed in New York City. It wasn’t in Siberia, some far-off place,” Rivera recalled on May 2. “I think the location had a lot to do with accelerating the public’s outrage. It started or accelerated a crusade.”

Rivera said he and others were witnesses to Willowbrook’s worst days as some residents returned decades later to remember and remind.

“It brings back such emotions, such memories,” Rivera said. “I really do feel in every regard that we are the living link to the grim, old days, to the nightmare when everything was horrible and covered up.”

Willowbrook decree ‘triggered’ incredible change

Attendees talked about the indignities of Willowbrook and the document that spelled its end: the 29-page Willowbrook Consent Decree, signed on April 30, 1975, by then-Gov. Hugh Carey. The decree became the basis of a bill of rights for the developmentally disabled, and a roadmap for reform.

“It is an event that triggered the way we see people with developmental disabilities,” said Willow Baer, acting commissioner of the New York State Office for People with Developmental Disabilities. “That we include people with disabilities in our lives and our communities.”

The decree noted that residents are presumed to benefit from education and are capable of “physical, intellectual, emotional and social” growth. It became a key step in ending the segregation of the disabled.

“For its time, the Wilowbrook Consent Decree was a radical departure from the prevailing practices around the country for caring for people with disabilities,” said Clarence Sundrum, an attorney and member of the Willowbrook Review Panel. “We’re talking about the evolution of inclusion.”

Erik Geiser, CEO of developmental disabilities group ARCNY, called the document and closing an “amazing milestone in the history of the disability rights movement.”

“It’s really a document of hope,” said Henry Kennedy, a parent of a woman with developmental disabilities and an attorney. “It, in many respects, is like some of our founding documents.”

Diane Buglioli, a former Willowbrook employee and founder of A Very Special Place, which employs 600 and provides services to nearly 2,000 disabled individuals, said advocacy mattered then and matters now.

“There wasn’t a personal thing about Willowbrook. It was a stark setting. They were understaffed and underfunded. The concern is that those same trends are happening now,” Buglioli said. “Those of us active in the field are concerned the pendulum will start to swing.”

Willowbrook began with good intentions on a smaller scale, but became unable to care for its thousands of residents as it grew.

“The conditions were not appropriate,” said Kristin M. Proud, executive director of the New York State Council on Developmental Disabilities. “They were not the conditions you would want to live in or for your children. They didn’t have any programming during the day. They didn’t have services. They weren’t learning.

As conditions worsened, a kind of mothers’ crusade and parental pushback launched with legal work by Murray Schneps, who represented residents, and work by parents and advocates such as his wife, Victoria Schneps, and others.

Victoria Schneps picketed at Willowbrook State School, where her daughter Lara became a named plaintiff in the Willowbrook class action lawsuit. (Editor’s note: She is owner of Schneps Media, the parent company of amNewYork.)

Concerns for the future

Many things have changed, including rules that outlawed medical experiments such as those done with Willowbrook residents who were given Hepatitis B.

“There is a bar against experimentation,” said Beth Haroules, lead counsel in the Willowbrook class action litigation. “There are an awful lot of issues we need to be concerned about. People need to be seen, need to be included. And we can’t turn the clocks back.”

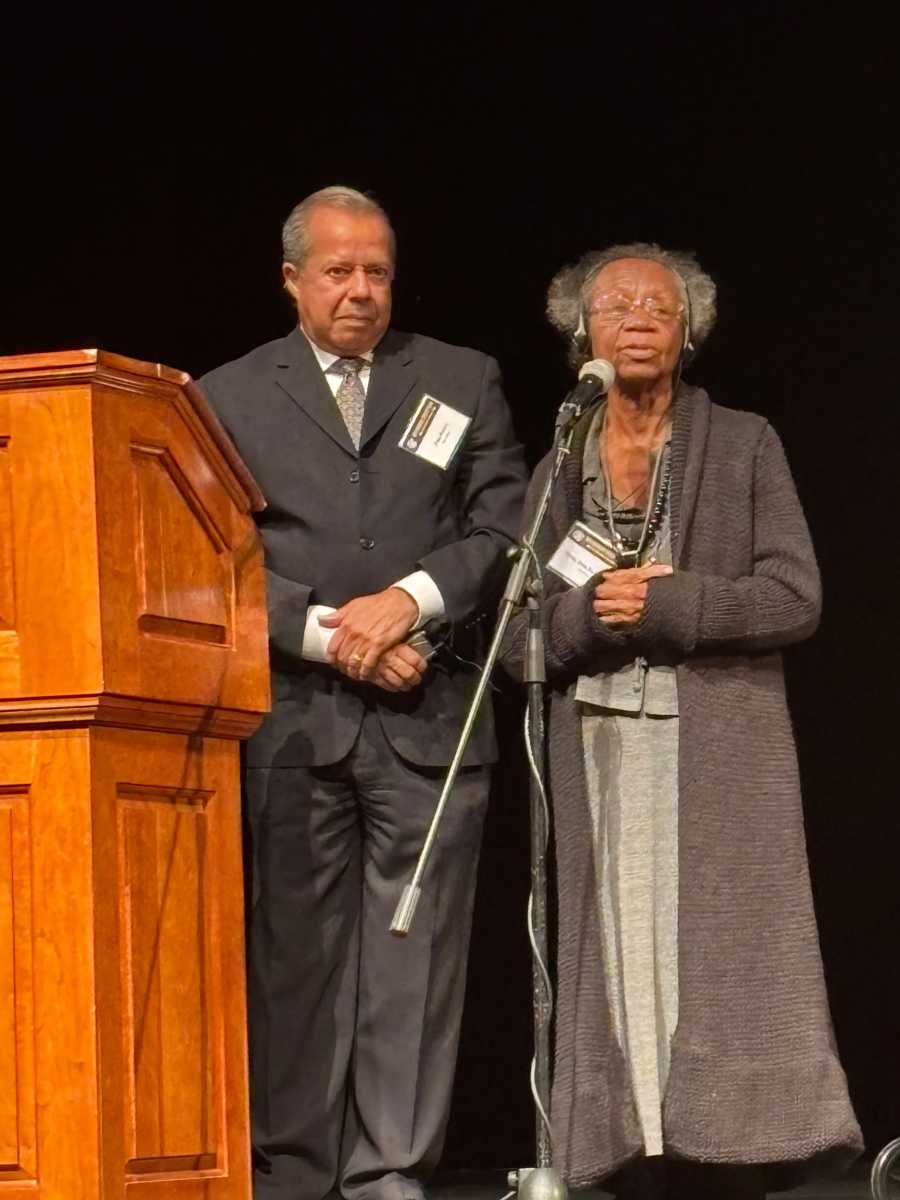

Willie Mae Goodman, 93, the mother of a daughter who had been in Willowbrook and an advocate, said we need to understand what unites us.

“All of us have a disability. None of us are perfect, not at all. I have a saying. ‘Everybody is somebody,’” she said. “There’s not one person that is a nobody.”

Victoria Guglielmetti, 28, who has a developmental disability, was at the event, not as an observer, but working for the Harvest Café.

“They changed my life,” she said of her employer as she served guests. “It’s my dream to become a chef.”

Today, people with disabilities can have and realize dreams, a far cry from Willowbrook, where a nightmare was more common.

“Today is about celebrating that many decades of advocacy have gotten us to where we are and led us to having individuals with disabilities living and working in the community,” Proud said. “It’s about making sure we don’t go backwards.”

Willowbrook’s Building 29 is being renovated and transformed into the Willowbrook Center for Learning, reminding people of what was and shouldn’t be again.

However, many at the anniversary expressed concerns about looming cuts to Medicare and Medicaid during the second Trump Administration.

“We cannot go back,” Haroules insisted. “You had understaffing, overpopulation, people with extreme needs whose needs could not be met.”