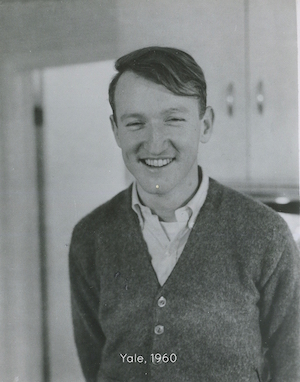

BY GERALD BUSBY | I came out while a junior at Yale in 1959, when a gay witch hunt brought me face-to-face with the campus police. The practice back then was to “catch” one of us expressing himself orally in a public restroom and then coerce him to reveal his cohorts. Shades of the House Un-American Activities Committee. I was named by one of those captured transgressors, brought to campus police headquarters, and told if I’d say what I did was wrong and name someone else, I wouldn’t be “fired,” Yale’s term for being expelled. I chose with considerable trepidation to say I was, and always had been, homosexual — but to my shame, I named another student I’d been intimate with.

I remember calling the police interviewer’s attention to other behavior in the men’s room I thought was far worse than men diddling each other — men sitting on toilets meticulously chiseling glory holes with pocket knives through the marble partitions that separated the stalls. Some holes were decorated peripherally with rococo flourishes of colored felt tip pens. I worked part-time for the university’s maintenance department — Operating Services it was called — that, without comment except for those of us who were gay, treated this vandalism as routine. They replaced the marble partitions just as they reupholstered leather chairs that were worn thin or had cigarette burns.

My case was referred for final judgment to the Master of Branford College where I lived. We called him Old Iron Jaw. “One bad apple spoils the barrel” was his argument, but then he acknowledged, “Times are changing. If you’ll agree that you’re abnormal and see a psychiatrist, we’ll let you off.” I agreed, traumatized but grateful to avoid further humiliation.

Years later Old Iron Jaw’s son contacted me for a tribute to his recently deceased father. I was surprised to hear myself saying his father had supported my coming out at Yale by not firing me. It was true, though inadvertent. I also told him that most of my gay friends at Yale had judged me harshly for admitting I was gay and not playing the game by the accepted rule — you could do almost anything you wanted, and look any way you liked if you never called it by its real name. My straight professors and one gay piano instructor in the music school supported me.

Most sympathetic was Nathaniel Lawrence, my philosophy of religion teacher. He’d been a protégé of Alfred North Whitehead at Harvard. Whitehead and Bertrand Russell were the authors of “Principia Mathematica,” an epic tome on the foundations of mathematics. Professor Lawrence was compassionate and understanding. Just two weeks before I had told him about bringing a hustler to my college room. When the hustler turned violent I called the campus police, but I didn’t press charges when he was taken into custody. He was only 19, it was his first offense, and I didn’t want him to have a criminal record. I’m sure I was thinking of myself in his position.

The next two years of psychotherapy with Dr. Arnstein were totally about admitting the error of my ways and changing my habits to align with acceptable behavior. I kept thinking, “This is Yale and it’s a misdemeanor to be gay.” In East Texas back then, it was a felony. Homosexuality was officially a neurosis in the world of medical definitions, and I remember Dr. Arnstein saying to me, “Does it really make you happy to make love to another man?” This was the nicest way he could say what he really meant: “Do really like to suck cock knowing that it’s abnormal?”

“Yes,” I answered. “It can make me very happy.”

I really didn’t think that I was making love with other men, though I sometimes had desperate crushes on them.

My virtuoso piano performances at Yale distracted me from such compelling urges, very much as they had when I was a teenager and played eight services a week in the First Baptist Church in Tyler, Texas. I wasn’t proud of my sexual identity, but I was proud of the ways I could create to connect with other men secretly, sometimes seducing them through my musical talent.

This was my modus operandi at 16, when I toured the south one summer with a Mexican Southern Baptist evangelist named Angel Martinez. I was the gospel piano player, and I ran the length of the keyboard with scales, arpeggios, and octaves that glorified the Lord. Angel himself was handsome and charming. He could quote from memory lengthy passages from the Bible while members of the congregation, mostly poor white people, marveled “how smart that Mexican is.” He was married to a woman who looked like Jayne Mansfield. Angel never came on to me, but the young doctor I was staying with in Sylacauga, Alabama kissed me passionately one night in bed. His name was Henry, and he tasted like tobacco. The Angel Martinez Gospel Team was hired for a two-week “Crusade for Christ” in a football stadium. Besides saving souls, we had to raise money to keep going.

My career at Yale as a pianist thrived. I accompanied the University Glee Club conducted by Fenno Heath, and I was featured in their programs playing Bartok’s “Suite Opus 14” or Chopin’s “Scherzo in C-sharp minor.” I also liked to sneak into practice rooms in the basement of Woolsey Hall and blast sustained sounds from the Holtkamp pipe organ. I wasn’t supposed to be there since I was a piano major. One morning the curator of organs, Mr.Thompson-Allen, stuck his head in the door and asked, “Is that Messiaen you’re playing?” “No,” I answered, “I’m just improvising.” With no expression on his face he responded, “In that case you’ll have to leave.”

I realize now that my identity as a gay man at Yale was really determined by others, my audiences, as it were, for sexual and musical performances. I remember no pride other than knowing for sure I existed if I had sex with another man. It didn’t matter how difficult or humiliating it might be, very much as an abused woman knows who she is because her lover beats her — abuse as a mode of existence. My gay life consisted of the challenge and tyranny of constantly pursuing pleasure. I was proud of my conquests at the piano and with other men. Nothing resembling gay pride had dawned on me.

When I graduated from Yale in 1960, I came to New York and got a job typing in an advertising agency like the one in “Mad Men.” The CEO was the most erudite gay man I ever met. He was German, elegant, and conspicuously successful marketing a diet drink called Metrecal. He owned the building that housed his agency on 51st Street between Madison and Park. He had Picasso ceramics on his desk; Paul Klee drawings and Matisse paintings hung on the walls in his office. He hired handsome young men as account executives, and I occasionally lunched with them at Reidy’s or the Yale Club. I was proud not necessarily to be gay, but to be included in this group of mostly straight men. I had just begun my journey as a homosexual in New York with a degree in music and philosophy from Yale. I could type faster than anyone else in the typing pool.

Gerald Busby is a longtime resident of the Chelsea Hotel and protégé of Virgil Thomson. He is best known for his film score for Robert Altman’s “3 Women” and his dance score for Paul Taylor’s “Runes.” With Craig Lucas, Busby is currently writing an opera based on “3 Women.” Busby’s life at the Chelsea Hotel is the topic of “The Man on the Fifth Floor,” a documentary film currently in production.