Hundreds of commuter ferries, tugboats, party boats, and even historic sailing ships braved the chaos of 9/11 to deliver as many as half a million souls from the clouds of toxic dust that engulfed Lower Manhattan after the World Trade Center collapse.

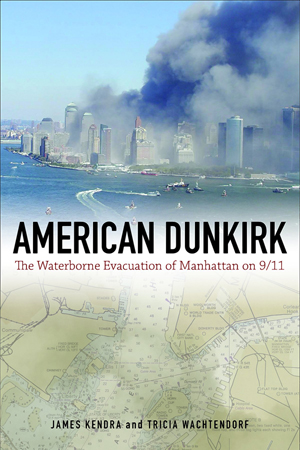

“American Dunkirk: The Waterborne Evacuation of Manhattan on 9/11” by James Kendra and Tricia Wachtendorf is published by Temple University Press.

BY COLIN MIXSON

A new book sheds light on an oft-overlooked aspect of the aftermath of the terrorist attacks of 9/11 — the massive waterborne evacuation of Lower Manhattan undertaken that day largely by civilian vessels and sailors.

James Kendra and Tricia Wachtendorf, co-directors of the Disaster Research Center at University of Delaware, compare the mass rescue operation to the historic evacuation of more than 300.000 British troops surrounded by the Nazis at Dunkirk in 1940, when an armada of lifeboats, fishing vessels, and pleasure craft spontaneously sailed to their rescue from across the English Channel.

Sixty years later, the aftermath of the World Trade Center attacks saw an even more massive operation, in which hundreds of commuter ferries, tugboats, party boats, and even historic sailing ships braved the chaos to deliver as many as half a million souls from the clouds of toxic dust engulfing Downtown, as the authors describe in their book, “American Dunkirk.”

The mass-rescue operation, though nominally coordinated by the Coast Guard, was largely ad hoc, with the skippers of individual vessels making crucial decisions on the fly in response to the rapidly changing conditions, according to the authors.

“What we saw was whether you were a member of the Coast Guard or the captain of a tug boat, they were able to make sense of their environment, and that’s part of the reason this improvised response worked so well,” said Kendra.

The book relies on the first-hand accounts of local captains, including Captain Patrick Harris, skipper of the nearly century-old Ventura sailing yacht, which docks at Battery Park City’s North Cove Marina.

He and other captains described a cool and sunny day that began like any other, but suddenly descended into a storm of dust, horror, and long-hours scouring Lower Manhattan’s waterfront for survivors wandering out of the dust cloud in a zombie-like daze.

Not long after the first plan hit the World Trade Center, Harris sailed from Battery Park City’s North Cove Marina aboard his historic sailboat to the South Street Seaport after hearing calls for aid on his radio, but, finding the area deserted, he turned back towards the Manhattan’s west coast. Then, as a northwest wind blew back the veil of smoke, the captain bore witness to a spectacle he’s not likely to forget, according to his account in “American Dunkirk.”

“I saw this V-shaped formation of about a half a dozen or so tugboats charging up in this direction, and I remember at the time it just reminded me of the old black-and-white footage you see of Pearl Harbor… There was so much smoke you really couldn’t see that blue sky, And it was actually very inspiring to see that, knowing those guys were going in there and that’s where all the trouble was,” Harris told the book’s authors.

“American Dunkirk” found its genesis in a study done by Kendra and Wachtendorf, funded by the National Science Foundation and the University of Delaware, to determine how unplanned, unscripted, and entirely improvised activities could lead to highly successful relief and evacuation efforts in the event of a major disaster.

In studying the 9/11 evacuation, they found that not only were hundreds of thousands of stranded New Yorkers evacuated to safety, but there were also no serious accidents or injuries as a result of that evacuation, despite — or perhaps because — communications were handled largely through civilian channels.

For instance, not only did the roughly 1,000 non-official vessels conduct most of the evacuations, but the civilian craft were also responsible for ferrying emergency personnel and materials into the disaster zone.

In that capacity, civilian captains were able to determine what vessels were best suited to what task, along with where they would dock and in what order — often with no oversight or logistical support from government agencies, according to Wachtendorf.

“You had tugboats bringing in medical supplies and personnel, and it was often up to the captains to figure out what vessels had what capabilities,” she said. “The Coast Guard was involved in that coordination, but it was very much coordinated amongst the captains themselves. They had all the knowledge, and they were able to figure it out, either by radio or by voice.”

The pair’s studies show that disasters are rarely single, self-contained events able to be handled by one leader, however competent, and are better described as a cascade of separate, related emergencies that arise from the swift and sudden changes in circumstances — as traffic shuts down, utilities cease to function, and lines of communication drop dead — and that in the heat of the moment, men and women of various walks of life can and should be trusted to use their various skills to bring aid to those who need it.

“Disaster is not a single thing that one person can control — it’s a community event,” said Kendra. “We saw an emphasis on, where there was leadership, it was based on communication and coordination, and letting things happen when they worked.”

The lesson of “American Dunkirk,” say the authors, is that officials should recognize the experience, professionalism, and courage of everyday New Yorkers — especially the grizzled old sea dogs who saved so many on that otherwise dark day.

“In the boat evacuation, the fact that these were members of a community who new each other, the environment, and their vessels very well, they proved very effective in that situation,” said Kendra.

Commuter ferries pulled directly up to the Battery Park City esplanade to load up panicked survivors for transport across the Hudson.