BY JACKSON CHEN | It’s unusually quiet in Queens, with only the lull of rainfall offsetting absolute tranquility. Most nearby residents are fast asleep ahead of their morning routine beginning with the rising sun, but a food trucker is awake at 3 a.m. and answering his phone that blares the whistling tune of “Yankee Doodle” to incoming callers.

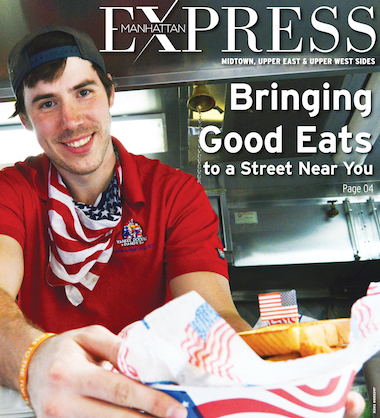

Josh Gatewood, founder and owner of the all-American cuisine Yankee Doodle Dandy’s food truck, throws on a bright red hoody stamped with its logo — a bald eagle in a stars-and-stripes top hat and suit. After downing a Red Bull for breakfast, he heads out into the silent darkness to pick up his truck at a commissary storage space a few blocks away.

After what is a 15-minute walk — but, today, is a five-minute drive because of the rain — Gatewood unlocks the gates that store his and many of New York’s other food trucks.

There’s only the glow of the truck’s interior florescent lighting as Gatewood and his three employees — Dave Ockrim and Abdel and Jamilia Idrissi — load in a day’s worth of chicken tenders, burgers, Texas toast, and fries.

As soon as the truck’s fully stocked, the team makes their way toward Manhattan. With only a driver’s and passenger’s seat, whoever doesn’t call shotgun is stuck in the kitchen area where each and every pothole the truck hits sounds like cymbals crashing.

“We’re here before the city’s awake,” Gatewood said of the cityscape absent of office lights as they drive over the Queensboro Bridge.

With no traffic at 4 a.m., the commute is only about 25 minutes as Gatewood makes it to Midtown Manhattan where they’d left one of their cars at around 6 p.m. the previous evening to secure their vending spot.

On West 46th Street between Fifth and Sixth Avenues, Gatewood parks his truck alongside many other food vendors, whose range of eats include breakfast, hot pastrami, halal food, and many other cultural offerings.

With Yankee Doodle Dandy’s spot secured for the day, the Idrissis sleep in the truck while Gatewood and Ockrim make a detour to purchase propane tanks before heading to the gym. And all of this preparation is conducted long before they’re open for business — beginning at 11 a.m. and usually running no later than 3 p.m.

While waking up at ungodly hours to secure their vending locale is one of the toughest facets of the food truck industry, it’s only one of the many problems the entrepreneurs run into.

On his red, white, and blue truck, it’s the splash of orange on his windshield that plagues Gatewood and many others on a daily basis.

“You get inundated with orange envelopes,” Gatewood said. “I have nightmares of orange envelopes chasing me.”

According to Gatewood, food trucks will “without fail” get a daily $65 ticket just for doing business because New York City has laws against vending from a metered parking spot, which blanket most of the food truck hot spots.

On some days, the city may double-down on food truckers with a more basic parking ticket if they’ve exceeded the limit of their Muni-Meter sticker.

But the most prohibitive city regulation that weighs down on the food truck industry is the limited number of Mobile Food Vending Unit Permits issued by the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. While that’s a matter Gatewood declines to comment on, the Street Vendor Project (SVP) — a nonprofit organization’s advocacy efforts on behalf of the city’s outdoor vendors — has been vocal about its goal of lifting the permits cap altogether.

The health department has limited the number of food vending permits in circulation to around 3,000, according to SVP, with an average wait time to win one of more than a decade. The hopeful food truckers need to navigate a black market system run by the permit owners to obtain the legal right to vend.

With such a limited number and a fast-growing demand, permit holders — who only pay $200 every two years to renew — can rent out their permits for exorbitant amounts in an unregulated manner.

According to Basma Eid, SVP’s organizer, his group has found that people who operate food trucks in Midtown have rented permits through the black market that cost them anywhere from $20,000 to $25,000 over the two-year life of the permit. While there are a modest number of seasonal mobile food vending permits that give additional food truckers the chance to work from April to October, Eid said those renting the shorter-term licenses can still expect to pay anywhere from $8,000 to $12,000.

Adding to the mobile food vending permit difficulties, Gatewood said all employees of food trucks are also required to obtain a Mobile Food Vending License, on which there are no caps, from the health department. Gatewood’s employees went through a four-to-eight-week waiting period and then completed a two-day course at a health department facility just to be able to work on Yankee Doodle Dandy’s.

The multiple burdens imposed on the food truck industry in New York City have left many owners losing money or even shutting their business down completely.

While there was a New York City Food Truck Association (NYCFTA) that advocated for them, its inactivity and eventual demise led Gatewood to attempt to revive the organization. After the leadership of the former NYCFTA abruptly abandoned ship, Gatewood — the former association’s vice president — said he’s looking to create a new and much improved version from the wreckage.

David Weber, co-founder of the now defunct Rickshaw Truck that offered Chinese-style dumplings, formed NYCFTA in January 2011. While Weber’s reasoning for the sudden shut down couldn’t be exactly pinpointed, Matt Geller, the president of the National Food Truck Association — which has a board director seat for the NYCFTA — and the Southern California Mobile Food Vendor’s Association, said it could be a number of reasons. Geller, a friend of Weber’s, said an association thrives on lots of engagement and determination.

However, Weber unexpectedly shut down NYCFTA in late March, leaving many food truck owners on their own. But refusing to give up on what the food truck association could be, Gatewood rallied the troops to see if they were interested in a second attempt that actually benefits its members.

“In March of 2014, I joined the food truck association,” said Gatewood. “I was expecting people to teach me the ropes, give me guidance, go to events with me, but that was not the case at all.”

To be a part of the NYCFTA, food trucks had to pay $99 a month in membership dues, but rarely received the benefits they were hoping for, Gatewood said.

“There was no one that really extended an olive branch and said this is where you need to park and this is what you need to do,” Gatewood recalled. “It was like you fend for yourself and figure it out through trial and error.”

According to Mohamed Salem, owner of pastrami food truck Deli n Dogz, the organization never even gave him a Twitter mention to its nearly 24,000 followers. Salem, who was a member of the former organization for over a year, said he eventually quit because of the absence of help and resources.

“They tweeted out some trucks, but as far as me, they never did,” Salem said. “It’s supposed to be like we get events or they tweet where you’re located, but they never do anything for me.”

In comparison, Gatewood said the Maryland Food Truck Association, of which he is also a member, sends out daily emails with catering opportunities or requests for food trucks. He lamented the lost business suffered here in New York, noting the city’s 8.4 million population compared to the 2.7 million people who live in the entire Baltimore metro area.

Gatewood said he has approached Weber for his assistance in making a smooth transition, but has heard no response. Gatewood has since enlisted the help of Geller, who offered free legal services and advice, as well as support from the national association.

“The market is New York, there’s nothing like it in the world,” Geller said. “New York has always fostered a strong food environment, but you’re also dealing with not a lot of land, so regulations are put in.”

With several years of running Yankee Doodle Dandy’s under his belt, Gatewood’s plan of action for the new association aims to address what he considers the main problems of the industry — parking, permits, and licensing.

At a May 3 meeting with ten food truckers — the second gathering for the new association — Gatewood was voted in as president, with Joe Glaser, who runs the Italian dessert truck La Bella Torte, elected vice president.

Gatewood is also in the process of forming an online message board where all interested food trucks can communicate and eventually form a database of frequently asked questions. On Geller’s advice, the new association president is also working on approval of bylaws before taking control of the inactive Twitter and Facebook pages of the former association.

After the 6 p.m. association meeting concludes, the Yankee Doodle Dandy team is off to secure parking for the next day. As Gatewood heads back to Queens to his table full of NYCFTA paperwork and parking tickets, he’s already thinking about getting ready to be up again at 3 a.m.