BY ZACH WILLIAMS | Four feet makes all the difference when it comes to installing a protected six-foot wide bike lane on Sixth Ave. between W. 14th and W. 33rd Sts.

By shaving one foot off of three traffic lanes and another from parking, the city can squeeze the upcoming bike route onto the west side of the avenue next year, representatives of the city Department of Transportation (DOT) said at a Nov. 18 meeting of the Community Board Four (CB4) Transportation Planning Committee. Though supportive of the new bike lane, board members expressed skepticism that the plan provides enough infrastructure to boost pedestrian safety.

The DOT plans to build the bike lane next year with an extension south to Canal St. possible in 2017, representatives said. Altogether, the city will add 12 miles of new bike lanes in 2016 as part of the ongoing Vision Zero initiative.

Twenty-seven painted “pedestrian islands” would form at the tip of the “floating” parking lane at intersections, reducing the crossing distance by 17 feet, according to the DOT. Without a raised platform, these areas cannot protect pedestrians, according to Christine Berthet, CB4 Chair and co-founder of CHEKPEDS, a Hell’s Kitchen traffic safety coalition (chekpeds.com).

“The cars are going to go up over it. The bikes are going to go over it. It’s not a pedestrian refuge anymore,” she said at the meeting. “I wouldn’t feel comfortable being over there.”

DOT representatives said that space is limited, but the proposed configuration would nonetheless boost safety for pedestrians, bicyclists and motorists. Slimmer traffic lanes of 10 feet would slow traffic, and the separation of bicyclists from moving cars reduces the possibility of crashes, according to the DOT.

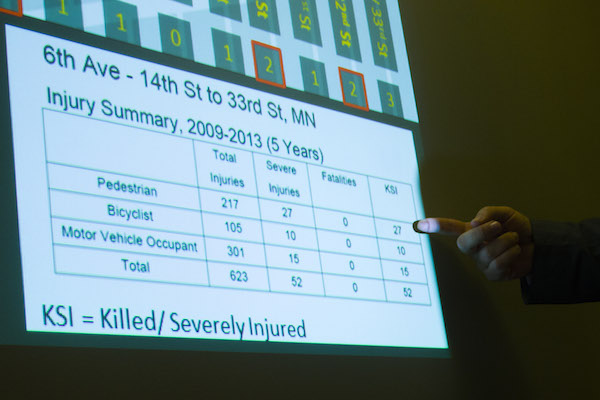

The same configuration was used on Second Ave., leading to a reduction of 46 percent in injuries, according to the DOT. Between 2009 and 2013, 623 people were injured in crashes on Sixth Ave. between W. 14th and W. 33rd Sts., with pedestrians accounting for half of the 52 serious injuries.

While raised areas would be ideal, DOT representatives said that the lack of space disinclines department engineers from approving a narrow concrete pedestrian island. City requirements also limit the project in other ways, including keeping the bike lane functional at all hours.

The plan would require the suspension of parking to allow street sweeping. The 11-foot wide clearance required by sanitation vehicles is not easily negotiated, DOT Director of Greenways Ted Wright said at the meeting. The nine-foot space between the curb and the parking lane presents other issues, said committee members. Garbage trucks have cans to empty throughout the day, and fire trucks and ambulances would not be able to use the bike lane as they do on Eighth and Ninth Aves., said committee member Walter Mankoff.

“Whether or not you put concrete down or don’t put concrete down, it’s not an issue of moving the cars for two hours. It’s an issue of parking all day long and I think you’re way off in terms of what you’re thinking. I think you need to take another really serious look at it,” he said.

Narrower street sweeping vehicles could fit within the nine-foot area, but the DOT officials pointed out that decision falls outside the purview of the department. But if the board wished to lobby the sanitation department, it ultimately could have a far-reaching effect, said Wright.

“They set the standard for the rest of the United States, apparently, so it would be a wonderful thing, and we have brought it up, but it’s a difficult conversation,” he said of convincing the sanitation department of adopting narrower vehicles.

The FDNY approves of the proposed design, added Wright. The department has to balance the needs of other city agencies with bicyclists who regularly complain to the DOT about city vehicles blocking bike lanes.

The implementation of split phase traffic signals — which have separate lights for through and turning traffic — requires that bicyclists, pedestrians and turning vehicles share space at the intersections of W. 14th and W. 23rd Sts. in what are known as “mixing zones.” Requiring that vehicles queue for a turn would alleviate pressure from through traffic to drivers trying to make a turn, said Preston Johnson, the DOT project manager.

Berthet asked the DOT why new signals would only be installed at the two intersections when injuries happen in large numbers throughout the bike route. Additional controls could further minimize collisions between cars and pedestrians by giving the latter dedicated time before allowing vehicular turns through what are known as leading pedestrian intervals, she said.

But such additional signaling could upset the balance the DOT seeks between safety and avoiding the potential gridlock, Johnson said.

“If we could go through the city and make every single movement go on its own phase we could, but then it would be a bunch of 20-second movements and everyone would be waiting 90 seconds longer for every single light,” he said. “[But] New Yorkers don’t like to be inconvenienced.”

The committee requested that the department return in two months with an update on the project. In the meantime, Berthet urged the DOT officials to focus on “why yes” rather than “why not” in regards to committee members suggestions such as leading pedestrian interval signals.

There is a department process to be followed, said Johnson, but he added that he would do what he can to satisfy the committee’s requests.

“If it was up to me, I would give you guys the (signals) in a second,” he said.