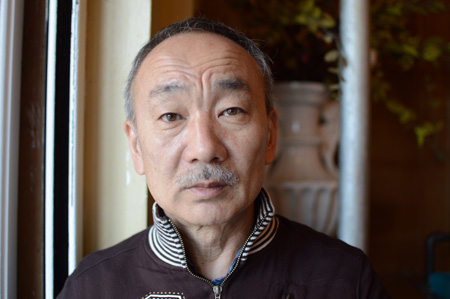

BY JACKSON CHEN | In his 30 years as a photographer, Q. Sakamaki has walked through the aftermath of 2011’s 9.1-magnitude earthquake and tsunami in Japan. He has documented the destruction and leftover rubble after the Israel-Gaza conflict in 2014. In New York, he covered the 1988 Tompkins Square Park riots in the East Village, where encamped homeless people, rebellious youth, and drug addicts clashed with police.

His photos capture extremely intimate moments where it seems humans are at their most exposed. Sakamaki explained that he is chasing the answer to the question of “what is the meaning of humanity, what is it to be a human being?” in his photography.

“Because I’m a photographer, because I’m a journalist, I would like to know what’s behind the scenes, why people fight, why people kill each other, always I’m thinking about it,” Sakamaki said of his thought process, during an interview near his Morningside Heights home. “And then I would like to catch something pretty, so actually doesn’t matter the passion: music, culture, or war.”

While he originally envisioned being a novelist or a fashion photographer, his passion for photojournalism sparked after he emigrated from Japan to the East Village in 1986. When he first moved there, he was shocked at the scene the encountered within Tompkins Square Park and in the surrounding neighborhood, comparing what he saw to a Third World country. But as he assimilated into the area, he became absorbed in the energy of those squatting in the park.

“Tompkins Square Park movement was expression of the people’s soul, how people are feeling naturally, instinctively,” Sakamaki said. “It touched me a lot.”

And after covering the gritty reality in the park, the protests, and the police brutality that came in response, Sakamaki began steering his photography efforts toward human rights. It was a natural bridge for him to cross given his interest in global affairs since the time he was a teenager, he explained. He completed his master’s degree in International Affairs at Columbia University, informing his future pursuits.

Since then, Sakamaki has traveled to an impressive range of countries, including Sri Lanka, Burma, Bangladesh, Haiti, Brazil, Sudan, Liberia, Egypt, and more. He has always been attracted to conflict and war zones. His camera equipment ranges from a Canon DSLR to his iPhone and, when it’s possible to use, a film camera. Due to the expense of developing film, however, that approach is often not feasible, which he regrets given its superior image quality to digital.

Sakamaki has, at times, put his life at risk to snap closely personal portraits that make the viewer feel as if they were there. Particularly in Cairo, his camera attracted unwanted attention and he was severely beaten by a mob, captured and jailed for several nights, and blindfolded and interrogated for being a photojournalist in an area he was not welcome.

He said he often heard, while blindfolded, people getting beaten until their voices vanished due to what he could only assume was their having passed out. Elsewhere, he was caught by a ricocheting bullet from an Israeli soldier and attacked twice in Brazil. While he produced, in each case, moving images that shaped his own understanding and experience of the world, he was left with a parting burden.

“After that experience in Cairo, I could contain, but some of the Israel-Palestine, got shot, also I was attacked in the streets of Rio de Janeiro twice, those experiences come together,” Sakamaki said of the post-traumatic stress disorder he now contends with. “I can’t deal with it. I thought I could manage to control, but sometimes no. That is dangerous.”

Whatever the personal cost, his dedication to his work has been widely acknowledged, securing for him several prestigious awards, including World Press Photo’s People in the News First Place Prize in 2007 for his coverage of the civil war in Sri Lanka.

“Compared to Sudan, compared to Angola, Sri Lanka is okay,” Sakamaki recalled. “Compared to the Israel-Palestine conflict, it’s a so-called ‘unseen war, unseen conflict.’ So I feel like I should, first, like to know what’s going on by myself. Second, I would like to tell other outside people.”

These days, he’s still just as attracted to the idea of understanding the humanity of others, but he’s beginning to incorporate introspection into his works of photo-documentary and fine art photography. In an exploration of his own sense of self, he is trying to capture an understanding of his own ever-developing personal identity. He explained that while he’s ethnically Japanese, he feels American, but he’s also traveled to many different countries where he picked up pieces of culture that also have shaped his identity.

He admits it all adds up to a complicated concept to wrap his brain around.

“I’m chasing my own identity, I’m actually in limbo all the time,” Sakamaki explained. “Ethnicity is part of it, culture, own experiences, and then changing the identity, step by step, slowly. Identity not only come from blood, not from religion. We can change it, it automatically growing, slighting changing, developing. The point is I would like to know how we develop those identities, those human acts to exist, to coexist with other people.”