BY DUNCAN OSBORNE | City contracts that were recently put out for bids add further evidence that government HIV prevention dollars are favoring biomedical interventions that prevent HIV infections, such as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), and moving away from behavioral interventions that seek to alter sexual behavior.

“Increasingly, biomedical HIV prevention approaches have emerged as yet another key tool for primary HIV prevention and also as a way to reduce HIV-related stigma,” Public Health Solutions, the city health department’s master contractor for HIV prevention contracts, wrote in the document seeking bids. “This new mix of biomedical HIV prevention, when offered alongside behavioral, structural, and other prevention interventions, is often called ‘combination’ HIV prevention and has the advantage of being adaptable to each and every individual.”

The bid document, which was released in late March, offered $10 million in contracts with $1.4 million dedicated to “Biomedical Prevention” and another $2.6 million clearly relying on biomedical interventions as a major component of the funded HIV prevention activity. The remaining $6 million funded needle exchange programs and outreach activities. The successful bidders will be announced in late May and the contracts begin on July 1.

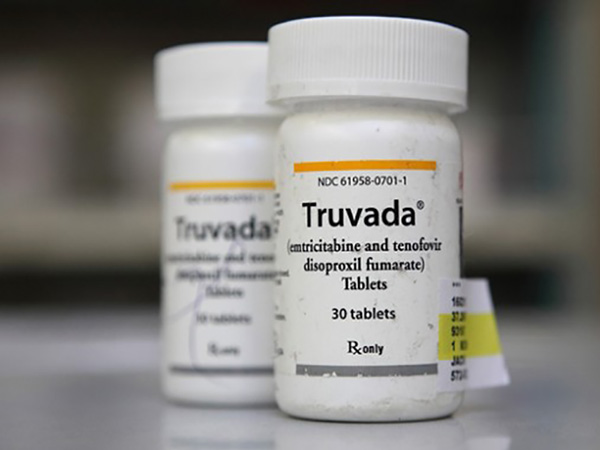

PrEP involves the use of anti-HIV drugs by HIV-negative people to keep them uninfected. Like needle exchange, which provides clean needles to drug injectors to prevent HIV infection, PrEP is highly effective when used correctly. Government funders in public health have paid for behavioral interventions, such as counseling, in the past, but the evidence supporting their efficacy was always scant at best. Such funders prefer interventions that have a proven effectiveness.

Federal and state HIV prevention dollars are also moving toward biomedical interventions.

On March 31, the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) announced $185 million in available grants for state and local health departments to fund PrEP and treatment as prevention (TasP) demonstration projects among men who have sex with men and transgender people. Just over $65 million of that is for projects targeting gay and bisexual men of color. TasP involves the use of anti-HIV drugs by HIV-positive people so they are no longer infectious.

The state budget for the current fiscal year includes $5 million to pay for PrEP-related costs for an estimated 600 people, though that program may cover more people. Last year, the state health department funded modest PrEP demonstration projects at seven health clinics, including the Callen-Lorde Community Health Center, the APICHA Community Health Center, and the William F. Ryan Community Health Network.

“We’re going to be looking at this as a high priority in our next budget cycle,” said Dan O’Connell, director of the AIDS Institute, which is part of the state health department, at a meeting on PrEP at a Ryan clinic in Hell’s Kitchen last year.

When Governor Andrew Cuomo endorsed a plan to reduce new HIV infections in New York from the current roughly 3,000 annually to 750 a year by 2020, his first action was to negotiate lower prices for the anti-HIV drugs the state buys that will be used for PrEP and TasP. For PrEP to contribute to that goal, tens of thousands of at-risk New Yorkers will have to be on the drug.

“One of the things that the task force recommended was shifting funding toward interventions that prove most effective in achieving the goal of ending the epidemic,” said Charles King, president of Housing Works, an AIDS group, and the co-chair of the 63-member task force that drafted the plan to get to 750 new HIV infections annually. “I think you’re going to see that in a lot of contracts.”

The task force, which was co-chaired by Dr. Guthrie Birkhead, a deputy commissioner in the state health department, also recommended allowing that department to change the goals and interventions funded in longer contracts.

“What you will see on a rolling basis is shifting contracts,” King said.

These shifts in funding appear to favor larger organizations with onsite clinics that do a lot of HIV testing, which can identify people who are having unsafe sex and may be PrEP candidates. PrEP requires quarterly screening for sexually transmitted diseases and checks for side effects. Larger groups that do thousands of HIV tests every year can also identify more previously undiagnosed HIV-positive people who are candidates for TasP. King said this change in funding did not necessarily mean that smaller organizations would lose dollars over time.

“The whole regime in healthcare is integrated systems, integrated networks,” he said. “That’s already done in HIV…None of these organizations have to go out of business.”

The Latino Commission on AIDS, for example, does not provide medical services, but it has linkages to medical providers. The commission performed 1,481 HIV tests in 2014 and identified 38 previously undiagnosed HIV-positive people. While that is not a lot of HIV tests, the two percent positivity rate, which is high, indicates that the organization is testing the right population. That could still be valuable to government funders.

“We have been able to build strong access to social networks,” Guillermo Chacon, the commission’s president, told our sister publication, Gay City News. “Many organizations like ours are essential to making that bridge.”