By Julie Shapiro

A long-awaited study of placard parking in Lower Manhattan shows that the situation is just as bad as residents, commuters and visitors suspected — and it may even be worse.

Vehicles with placards — special permits that allow government workers to park their personal vehicles for free — take up 43 percent of all legal spots in Lower Manhattan. There are so many government-issued placards that the demand for Downtown spaces outstrips the supply of legal spots, and when government cars run out of room, they displace shoppers from parking meters and delivery trucks from loading docks. Drivers with placards are also notorious for blocking fire hydrants and straddling sidewalks.

To quantify this problem, the city Department of Transportation released its $570,000 study last month in the midst of the debate over congestion pricing. Community leaders had been calling on the D.O.T. to release the study, begun in 2006, since it was rumored to be complete a year ago.

“It shows what everyone already knows: that parking Downtown is a mess,” said Wiley Norvell, communications director at Transportation Alternatives. “The number of placards far outstrips what’s available Downtown in terms of legal on-street parking.”

That is especially true for vehicles with law-enforcement placards: Demand outstrips supply by 127 percent, leaving thousands of police officers with few legal choices to take advantage of their free perk.

Left, a graph showing the distribution of vehicles, broken into user groups, over the course of one day in the study conducted in 2006. The 85 percent line represents an ideal maximum occupancy rate. Right, a graph breaking down the vehicles observed into the major catagories.

“It’s damaging,” Geoff Lee, a Chinatown activist, said of the report. “It shows everything we’ve been talking about for years.”

Jeanie Chin, of the Civic Center Residents Coalition, added, “This is the smoking gun we’ve been waiting for.”

The D.O.T. gathered the data for the study, funded by the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation, over 11 two-day observation periods in September and October 2006.

“Lower Manhattan has a very unique situation in that there is a large number of city, state and federal agencies as well as the state and federal court systems located in a small geographic area,” said Seth Solomonow, D.O.T. spokesperson, in an e-mail. The results showed that placards have a large impact on the number of spaces available to the public, which was not surprising, Solomonow said.

The study shows that between 9 a.m. and 5 p.m., 93 percent of spaces below Canal St. are occupied, meaning that cars continually circle the streets looking for a spot. Lining the crowded curbs are vehicles displaying parking placards.

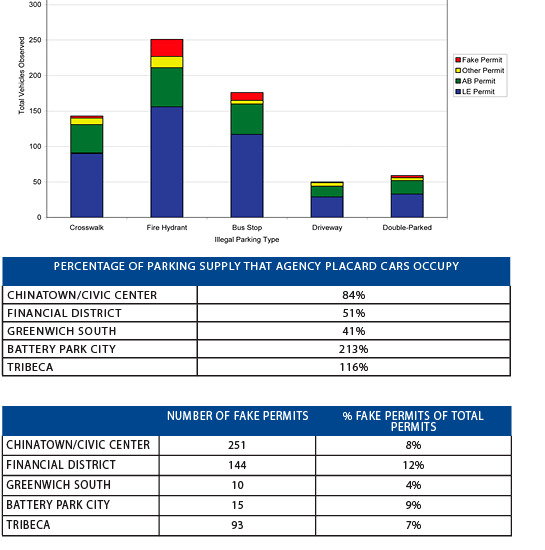

Of all 5,203 placard vehicles observed Downtown, nearly one in eight parked illegally at a bus stop, crosswalk, fire hydrant or driveway, or double-parked. To make matters worse, vehicles with placards park for longer on average than private cars: 4 hours for placards compared with 2.7 hours otherwise. Most government agency permits come with a three-hour time limit — a rule permit-holders ignored 42 percent of the time.

When drivers with placards run out of spaces in areas specially designated for them, and they don’t want to park illegally, they spill over into areas that inconvenience the community. In Lower Manhattan, placard parkers removed 22 percent of loading zone spaces and 18 percent of metered spaces, which activists say has had a palpable effect on small businesses.

“People’s day-to-day lives are suffering,” Norvell said. “Businesses can’t get deliveries, bus riders have to board in the middle of a busy roadway and pedestrians have to walk in the street.”

Another side of the problem is the prevalence of fake permits, which range from photocopied versions of the real thing to official-looking placards citing imaginary agencies. Some government workers drape a counter-terrorism booklet across the dashboard or stick an orange construction cone on the hood — methods that shouldn’t earn them immunity from parking tickets, but neighbors see the same cars with the same fake placards over and over, without tickets. Of all the placards the D.O.T. surveyed, 9 percent were fake.

The report also noted that the actual number of fake permits could be much higher than the 513 counted, because there is a large variety of real and fake permits. That means that traffic cops themselves may have difficulty distinguishing between the two, especially when less than half of the permits are displayed in the vehicles to which they are registered. As the report adds, “It is unknown what the consequences are to enforcement officials for making an error involving a real permit, but one assumes that the risk is not worth taking in most cases.”

And that, activist Jan Lee says, is just the problem.

“We see the [D.O.T. report] as proof that the city’s governing of itself doesn’t work when it comes to abuse,” said Lee, Geoff’s brother.

He has some reservations about Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s initiative, announced in January, that would reduce permits by at least 20 percent, limit the agencies that can issue them and create a working group and new N.Y.P.D. enforcement unit focused on parking placards. The city’s focus on the problem is great, Lee said, but he wants to see civilians on the working group to make sure the rules get enforced.

The 20 percent reduction “will have a significant impact on parking in Lower Manhattan,” said Solomonow, of D.O.T.

The focus on placard parking comes in the midst of the decision-making on congestion pricing, which passed the City Council 30 –20 Monday night. Parking advocates fall on both sides of the congestion pricing debate with Norvell ardently supporting it and Chin and the Lee brothers strongly opposing it.

The D.O.T. report comments on the problems associated with the N.Y.P.D. controlling its own permits.

“Because [law-enforcement] permits are issued by the police agencies themselves, there are few ways of ascertaining the legitimacy of these permits, nor of controlling the supply,” the report states.

A common misperception is that police officers are entitled to placards — on blogs, many officers respond angrily to the idea that one of their job’s few perks could be taken away — but the placards are more tradition than law. The police union contract requires that the city make a good-faith effort to provide officers with space to park at the precinct, said a source familiar with the contract, who spoke on the condition of anonymity. “It’s not a hard requirement,” he said. “It’s open to interpretation.”

The N.Y.P.D. declined to comment for this article.

The Lees and other local activists have worked successfully with the Fifth Precinct in ramping up enforcement on Mott St. in Chinatown, with officers ticketing and towing illegally parked cars. However, the officers are hampered by a lack of signs marking the area as a No Permit Area, so they tape up printed signs and enforce the rules. The Chinatown parking activists have long advocated for permanent signs, not just because they would make enforcement easier, but because putting up paper signs takes up officers’ time while manpower is limited.

Much of Lower Manhattan is a No Permit Area. In a rough trapezoid bounded by Canal St. to the north, W. Broadway to the west, Vesey St. to the south and Park Row and Bowery to the east, no law-enforcement or agency permits are allowed, unless signs name a specific agency as an exception. In a triangle bounded by Frankfort St. to the north, Broadway to the west and South St. to the east, law-enforcement permits are allowed but agency permits are prohibited unless posted signs give an exception.

The little-known No Permit Area is largely ignored and unenforced, but D.O.T. has no plans to put up signs. Solomonow said traffic agents can always look at the small maps of the no-permit areas printed on D.O.T.-issued placards if they do not know them, but D.O.T. does not issue the permits to police.

“Every agency business parking placard D.O.T. issues has a map on it denoting the ‘No Permit’ zones, so signs indicating the same thing are not necessary,” said Solomonow, of D.O.T.

The refusal to put up signs frustrates parking activists.

“All we’ve been asking for all these years is that they enforce the law,” Chin said as she walked along Worth St., a major east-west corridor, pointing out illegally parked cars. The cars, parked in no-standing zones and in bus stops, reduce Worth St. to one lane, making it hard for emergency vehicles to get through, Chin said. On Mulberry St., the only placards allowed are those with a specific agency code, but cars with a variety of other placards line both sides of the street, sprawled halfway onto the sidewalk. The problems are exacerbated by the proximity of Police Headquarters — meaning more law-enforcement placards — and the number of streets closed for security reasons, Chin said.

The D.O.T. report divided each statistic into five neighborhoods: Chinatown/Civic Center, Financial District, Greenwich South, Battery Park City and Tribeca. Battery Park City had the least parking available during peak hours and, as it is largely a residential neighborhood, had far more private vehicles than the other neighborhoods, with 74 percent private vehicles. Chinatown had the most fake permits — 251 — but the Financial District had the highest percentage of them, 12 percent of all permits and 5 percent of all vehicles.

In Lower Manhattan, there are actually more than enough spaces for all the government agency placards that want to park, but the spaces aren’t always in the right place — leaving some neighborhoods overflowing and others with plenty of room. The D.O.T. calculated the supply of spaces in each neighborhood, and then determined demand by counting the number of placard cars on the streets.

In the Financial District and Greenwich South, the agency cars use about half of the allotted spaces, while in Chinatown they use 84 percent. But in Tribeca, the agency cars use an extra 15 to 25 percent beyond what’s allocated to them. While Battery Park City sees a relatively low number of agency cars, demand is more than double supply — which could mean that Battery Park City residents with placards are using their agency permits to park by their homes. This seems especially likely given that the study’s observers found there were more permit cars in Battery Park City outside of normal business hours than between 9 a.m. and 5 p.m.

All the neighborhoods except Battery Park City saw a large percentage of law-enforcement permits. The 133 vehicles observed in Battery Park City represent two-thirds of all placards, but only 8 percent of all vehicles.

Jan Lee and other activists were glad to see the report released — it vindicates years of complaints and activism — but they wonder why it took so long to be made public. The study was rumored to be complete but so damaging that D.O.T. delayed releasing it.

“There was a great deal of analysis and quality control work,” replied Solomonow, of D.O.T.

Activists also said the report doesn’t show a complete picture.

“You can’t qualify the emotional toll in a report,” Lee said, tapping an orange binder containing a copy of the document. “That’s what’s missing.”

When placard cars park illegally in front of churches during funerals, the hearse has to double-park, leaving the pallbearers little choice but to awkwardly pass the coffin over government vehicles, Lee said.

“That breeds resentment toward city government,” Lee said. “These are the indignities that this neighborhood has had to suffer.”

Lee would like to see a computerized system that tracked each permit holder’s schedule and need for spaces, to ensure that the permits are only used for business.

Norvell agreed that the D.O.T. report confirms the need to rein in placard abuse and step up enforcement. He is optimistic because city officials are at least changing the way they talk about permits.

“They’re much more frank about the scope of the problem than they were a year or two ago,” he said, “but at the same time we need some pretty drastic action.”

Julie@DowntownExpress.com