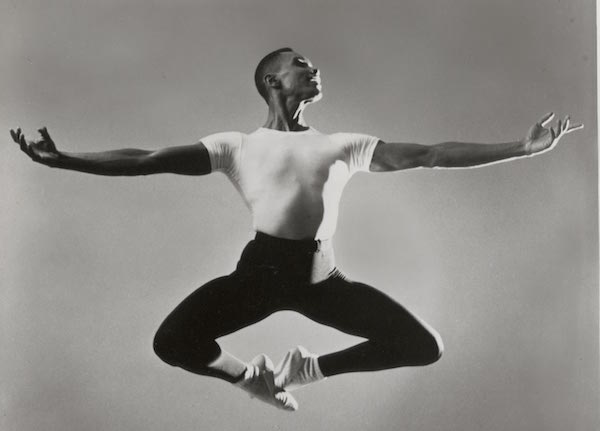

BY ZITA ALLEN | Arthur Mitchell, the pioneering ballet dancer, artistic director, and choreographer who, in the 1950s, became the first African-American principal dancer with the New York City Ballet (NYCB) was celebrated at Columbia University October 27 and 28.

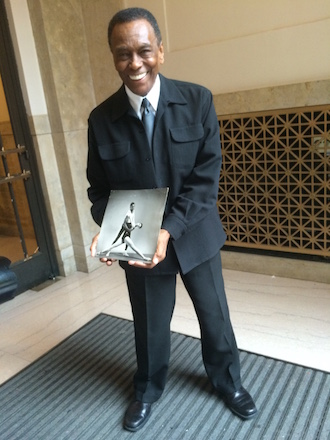

The occasion marked Mitchell’s donation to Columbia of his archive — a treasure trove of photographs, posters, clippings, and correspondence with the likes of Igor Stravinsky, Josephine Baker, Alvin Ailey, Geoffrey Holder, Carmen de Lavallade, David Dinkins, Mikhail Gorbachev, and Nelson Mandela. The archive also includes film footage and other material documenting an amazing life, a stellar career, and the impact of a man whose life has helped change America’s cultural landscape.

On October 26, the two-day event, entitled “The Arthur Mitchell Project Symposium,” opened with a retrospective of the career of this self-described “political activist through dance,” among whose achievements was the co-founding in 1969 of the Dance Theatre of Harlem (DTH).

The centerpiece was a conversation between Mitchell, who is now 81, and friends, including icon Carmen de Lavallade, former NYCB ballerinas Allegra Kent, a Barnard College dance professor, and Kay Mazzo, a founding member of the George Balanchine Trust. Barnard professor Lynn Garafola, who co-chairs the Dance Department, moderated as Mitchell recalled how, when he was a young teen, dancer Mary Hinkson introduced him to the Katherine Dunham School where future mentor and DTH co-founder Karel Shook taught ballet. Mitchell also expressed heartfelt appreciation for NYCB’s founder and choreographer George Balanchine and co-founder Lincoln Kirstein when recounting his historic admission to that company and how, years later, Balanchine made generous gifts of his own masterpieces and more to Mitchell’s fledgling company.

Punctuating these and other moments were film clips of Mitchell partnering Hinkson in Balanchine’s “Figure in a Carpet” or dancing with de Lavallade in Donald McKayle’s classic “Rainbow ‘Round My Shoulder.” There was also a clip of Mitchell partnering Kent in the “Agon” pas de deux that Southern TV stations refused to air because it featured a black man dancing with a white woman.

The two days were full of such reminiscences as well as analytical insights shedding light on Mitchell’s illustrious career and his tremendous impact on the nation’s arts and culture.

Three panel discussions on October 27 focused on the key role Mitchell’s archive can play going forward in incorporating African Americans’ stories and influence into our understanding of ballet history. One panel tackled the role Mitchell and DTH played in creating opportunities for other artists of color. Moderated by Pulitzer Prize-winning columnist, author, and Columbia professor Margo Jefferson, that panel included former DTH principal Karen Brown, one of the few black women to serve as artistic director of an American ballet company (Oakland Ballet), Karyn Collins, a Rutgers University journalism professor and dance critic, Robert Garland, a DTH choreographer and former principal, DTH founding music director and composer Tania León, and Vernon Ross, former DTH wardrobe master and designer who now works with the Metropolitan Opera and Radio City Music Hall.

Another panel looked at the importance of Mitchell and Shook, his DTH co-founder, having created an institution that included not only the company but a school and an outreach component, as well. Moderated by Brent Hayes Edwards, a Columbia professor of English and Comparative Literature, it included former DTH principal ballerina and current artistic director Virginia Johnson, Pulitzer Prize-winning Washington Post critic Sarah L. Kaufman, Florida State University professor Anjali Austin, a former DTH dancer, and Barnard’s Garafola.

The third panel discussed the political, cultural and socio-economic turmoil of the Civil Rights era and its impact on Mitchell’s decision to create DTH and debunk all the myths and bugaboos that plagued aspiring black ballet dancers for so long. This panel also grappled with questions about how to build on advances into this once taboo dance territory that were made by Mitchell and, more recently, Misty Copeland. Kendall Thomas, a professor and the director of the Center for the Study of Law and Culture at Columbia’s School of Law, moderated a panel that included this writer, who is a contributor to the Amsterdam News and the first black critic for Dance Magazine, Harlem Stage director Patricia Cruz, Farah Jasmine Griffin, an English and Comparative Literature professor at Columbia University, and Brenda Dixon Gottschild, author and professor emeritus at Temple University.

Praising Mitchell for his decision to donate his archives to Columbia was former Columbia Law School dean of students Marcia Sells, who this year left the university for the same post at Harvard Law School. The archive is currently being sorted and catalogued thanks to funding from the Ford Foundation and is expected to be open to the public in 2017.

“I believe that dance, and the arts more broadly, can be used as a catalyst for social change — this is why I started the Dance Theatre of Harlem,” Mitchell told one reporter. “With these materials now at Columbia, artifacts of American dance history and African-American history will be accessible to academics and the general public, furthering this change.”