BY SCOTT STIFFLER

“Tropical Malady” director takes you on another dreamy trip

Lush and peaceful and afterlife-friendly, you could do a lot worse than the Thai countryside when choosing a good place to die. Just don’t try to book a room at Uncle Boonmee’s tamarind and honey farm. Outside the realm of cinema, it’s nothing more than a pleasant fiction. You might as well be chasing a ghost.

As for Uncle Boonmee, the ghosts come to him. Bloated and weak from a bad kidney, he’s got an aura of impending death which attracts deceased loved ones and lost kin to his dinner table like bees returning to the hive. They’ll be treated well, though. Because when Boonmee gathers honey to show his guest its unique sweet and sour quality, he gently shoos the bees by telling them to “run along.” Getting back what he gives, Boonmee spends his last mortal days surrounded by doting caretakers both living and dead — while contemplating previous human and animal lives and wondering what role past deeds played in sealing his fate.

In “Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives,” return and renewal are front and center on the left and right brain of writer/director Apichatpong Weerasethakul.

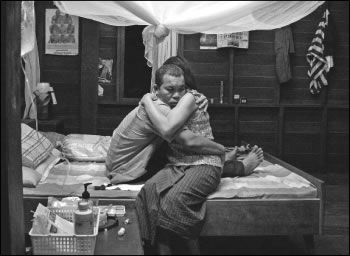

Whether it’s in the form of a city dweller coming back to the country, a ghost wife materializing to drain lethal fluids from Boonmee’s side, a beast of burden reclaimed after snapping its rope or a prodigal son showing up for dinner in the form of a Monkey Ghost, notions of escape and reinvention are accepted with a matter-of-fact calm that fits like a puzzle piece with the rhythms of the forest or the sparkling walls of a mountain cave.

Trippy enough for you? Strange? Surreal? These are thoroughly Western buzzwords — and straws to grasp at — when trying to suss out what possible author’s message is embedded within a film that purports to be concerned with the reflections of a dying man but makes a jarring narrative detour to lavish its attention upon a disfigured princess who offers jewelry, and herself, to a talking catfish lake spirit.

American audiences may be perplexed, but not necessarily alienated, by the film’s content and pace. There’s not a gunfight or a gross-out scene or a lovelorn vampire or a linear good vs. bad story to be found. Instead, there’s prolonged contemplation and sparse dialogue (good news for those who may be put off by the thought of having to read and process too many subtitles).

Weerasethakul mines the power of silence through lingering shots of the jungle that seem to go on forever; although you’d be out of pocket if you confidently bet they lasted more than fifteen seconds. Time keeps on slipping, too, in three seemingly epic-length scenes of Boonmee’s kidney being drained — including one painterly framed session during which a trickle of fluid snakes its way across the floor of a cave. Add to that giddy snapshots documenting a Monkey Ghost palling around the countryside with soldiers, and a tech-friendly monk who visits his relative in a hotel room only to invite her out for dinner while some doppelganger or ghost or parallel version of themselves stay behind to watch TV. The there’s the mist, mosquito netting and veils that either shield one world from another or give us a foggy glimpse of things to come on the other side.

Many (well, most) of these and other scenes defy rational or narrative explanation. But the sly cumulative effect lulls viewers into a heightened sense of appreciation for existing in a state of passive acceptance that comes with a melancholy kick as bitter as the tea Boonmee serves. Once you’ve acquired a taste, which you will, make it a high priority to spend some time with a DVD of Weerasethakul’s similarly incomprehensible, slightly more compelling, enduringly beautiful 2004 film “Tropical Malady.”