By Julie Shapiro

The Environmental Protection Agency has poured millions into searching for lead and other 9/11-related contaminants in Downtown apartments. But once the federal agency finds lead, it does not follow up to make sure the lead is permanently gone. Nor does the E.P.A. warn neighbors that their children could be living in unsafe conditions.

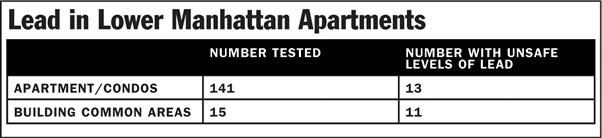

The E.P.A. has found lead dust, likely from crumbling lead-based paint, in 10 percent of the apartments below Canal St. and 73 percent of the building common areas they tested since last year. The E.P.A.’s usual cleaning methods get rid of the dust, but not the paint, so the source of the contamination remains.

And since the E.P.A. isn’t telling anyone where they found the lead, residents probably would not know the E.P.A. found it in their building — even if the lead was right next-door.

Of 141 apartments tested so far, 13 apartments in 13 different buildings had dust samples containing dangerous levels of lead. The E.P.A. also tested 15 buildings’ common areas, like elevators and stairwells, and found high levels of lead in 11 of them. In every single case, the E.P.A. found lead-based paint nearby, said Mary Mears, spokesperson of the E.P.A.

“We know lead is a problem,” Mears said. “It is absolutely no surprise to anyone.”

Lead-based paint is most common in buildings built before 1960, but it was used up until 1978.

As part of its Test and Clean Program, the E.P.A. offered to clean all the apartments and common areas where inspectors found lead or other contaminants, but the cleaning is superficial — it will not remove the root cause of the lead dust, which is the peeling paint itself. The E.P.A. explained this to the tenants and apartment owners and gave them leaflets explaining how to make the building safe, Mears said.

However, no one is checking to make sure the landlords fix the problem.

Mears initially said that the E.P.A. gave the city Health Department the addresses of the buildings with high levels of lead, so the Health Department could follow up. However, she later clarified that the E.P.A. would only give an address to the Health Department if the E.P.A. knew that a young child in the apartment had lead poisoning.

Nancy Clark, assistant commissioner for environmental disease prevention at the Health Department, wants a list of all the addresses with lead exceedences so she can make sure the buildings are safe.

“We’d like to reach out…so we can inform the building owner that if they have lead paint in their building, they can take steps to identify the hazards and take corrective actions,” Clark said.

But she can’t reach out, she said, when she doesn’t know whom to reach.

The E.P.A. has repeatedly refused to release a list of the addresses from its 9/11 cleanup programs, saying it is the federal government’s policy to keep that information private.

Rep. Jerrold Nadler has been one of the most strident critics of E.P.A.’s Test and Clean Program, and he remains concerned about the results.

“I certainly hope that if the E.P.A. has knowledge of unsafe levels of lead in any building, they are taking the proper steps to protect the health of all the occupants,” Nadler said in a statement to Downtown Express. “We have already seen the disastrous results when the E.P.A. fails to disclose all the relevant information that would impact public safety and health.”

The E.P.A. has spent $3.8 million so far to conduct the tests and clean the contaminated apartments. The E.P.A. conducted an earlier Test and Clean Program in 2002 and 2003, which included more apartments and the exteriors of buildings, and cost $30 million. During that program, the E.P.A. also found lead in newer apartments. Some of these buildings contained no lead-based paint, meaning the lead could have been connected to the World Trade Center collapse.

The E.P.A.’s Test and Clean Program is voluntary, which means tenants can enroll independent of their landlords and of each other. If only one tenant in a building enrolls, then the E.P.A. only tests that one apartment. Other tenants wouldn’t even know the tests are taking place — much less what the results are. That means that they could be living next door to an apartment with peeling lead paint and have no idea.

If one apartment in a building has a lead problem, chances are that the other apartments have a problem as well, said John Adgate, associate professor at the University of Minnesota’s School of Public Health, division of Environmental Health Sciences.

“There may be a good legal reason,” Adgate said, referring to the E.P.A.’s decision not to inform all tenants of the lead problem in one tenant’s apartment. “[But] on the face of it, it’s stupid.”

The government can override privacy concerns if they see an acute risk to public health, Adgate said, but he is not sure potential lead contamination would fall into this category. Swallowing lead paint dust can cause brain damage for young children — and even, in high doses, kill them — but lead is not considered as harmful to the general population. Lead paint does not pose a risk unless it is peeling and flakes into dust. To eschew the privacy agreement, the government would need to know that children live in the apartment and that the building is in poor repair, Adgate said.

But the government shouldn’t go overboard with notification, said Joseph Graziano, a professor of Environmental Health Sciences at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health. He frequently gets phone calls from parents who are upset about what he sees as minor risks.

“The stress caused by notifying people, by crying wolf, might outweigh the good intent,” said Graziano, who developed succimer, a drug widely used to treat children with lead poisoning.

Graziano added, though, that scientists are discovering that even small amounts of lead in children’s blood can have negative effects. As technology improves, doctors can detect lower levels of lead, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention continues to drop the maximum allowable level. Even in children who are within the boundaries considered “safe” by the C.D.C., scientists have found subtle effects when examining large groups of children, Graziano said.

Even if the Health Department received the addresses of apartments with lead exceedences, all they can legally do is send a letter, Clark said. Condo and co-op owners are responsible for maintaining their own space, which means the Health Department can do little without the owner’s permission. Condo owners should have seen a lead-based paint disclosure when they closed on the property, Adgate said.

Landlords of multi-unit buildings face stricter standards from the city. If a child under 6 lives in an apartment containing lead-based paint, the landlord must inspect the apartment every year for peeling paint and dust. Landlords must tell tenants the results of the lead inspection and, if they find peeling lead paint, they must fix it. If they don’t, or if they do the work in an unsafe way, tenants can call 311. The Department of Housing Preservation and Development will inspect and possibly do emergency repair work, charging the landlord, Clark said.

That means that it’s up to the tenants to notify the city of lead problems. But in the case of the E.P.A. program, tenants in the affected buildings will not know about lead in their building if they did not participate in the E.P.A. program. They also may not realize it’s their responsibility to check whether their landlords are following the law.

The E.P.A. does not track whether the lead exceedences are in condos or apartment buildings.

There could be thousands of apartments in Downtown buildings where the E.P.A. found lead, if some of the lead samples were found in large buildings. Or the number of at-risk apartments could be in the dozens if all the lead was found in small walk-ups. The E.P.A. also has not released information about the size of the buildings.

As Mears, the Environmental Protection Agency’s spokesperson, sees it, the agency does not have an obligation to inform all the building’s tenants of the test results, because the tenants aren’t any worse off now than they were before the tests.

“It’s not as though E.P.A. is discovering something new,” Mears said. The purpose of the Test and Clean Program is to search for and eradicate 9/11-related contaminants, not to battle lead paint, she said.

Doctors are supposed to test all children whom they treat for lead poisoning at ages 1 and 2, which would catch any problems and inform parents, Mears said.

The Test and Clean Program has been controversial from the start. Local environmental advocates said the tests were designed to find nothing. They questioned the timing of the E.P.A.’s tests, their methodology and their scope. The E.P.A. is still testing and cleaning apartments below Canal St., though enrollment is closed, and Mears expects the program to finish by the end of summer.

The E.P.A.’s tests differentiate between dust samples from accessible spaces, like counters, and infrequently accessed spaces, like windowsills. Of 13 apartments with lead exceedences, seven had lead in accessible spaces.

The E.P.A. also tested samples from building common areas. All 11 buildings that tested high for lead had exceedences in both accessible and infrequently accessed common areas.

Some of the apartments with lead could be in buildings with lead in the common areas, but the E.P.A. does not track the overlap, Mears said. People could track the lead dust from their apartments into the common areas, or vice versa, she said.

Julie@DowntownExpress.com