By Lincoln Anderson

Although the Parks Department probably wishes the issue would just go away, Soho art activists and Community Board 2 are not giving up their effort to restore Bob Bolles’ scrap-metal sculptures to a small triangle park by the Holland Tunnel.

The issue, a potentially precedent-setting case involving public art, was on the agenda at Board 2’s Parks Committee meeting on Thursday night.

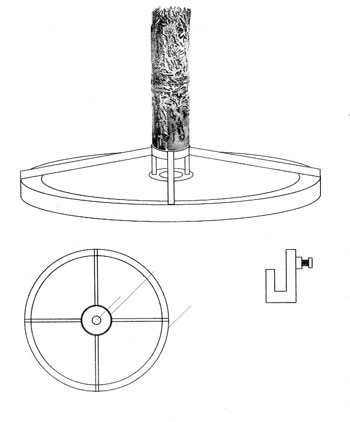

For now, the art activists are focusing on returning at least one sculpture, Bolles’ “Tree of Life,” to the park, located at the intersection of Broome, Watts and Thompson Sts. At last Thursday’s C.B. 2 meeting, they distributed copies of a diagram showing how the sculpture would be professionally installed at the site; a solar-powered light would illuminate the pipe’s interior at night, shining out through the hundreds of small cutout figures and filigrees on its surface. The artists say they would pay for the installation and raise funds to cover insurance costs.

For years, Bolles’ sculptures covered what was then an asphalt traffic island. Bolles, a Gypsy, carved the “Tree of Life” on the site with a blowtorch from a large metal pipe. It was his last major work before he died in 1980. The sculptures were removed from the location about three years ago, when the Parks Department renovated it into a small, planted park, and are stored at a Parks facility on Randall’s Island.

The artists group is concentrating on getting the “Tree” returned because its ownership is clear, meaning it can be donated; it currently belongs to Aaron Rose, a Soho photographer, who bought it from Bolles to preserve it from vandalism, and who is willing to donate it for the park.

The activists point to a C.B. 2 Parks Committee resolution from three years ago (when the late Tony “Mr. Parks” Dapolito was the committee’s chairperson) that set conditions that were agreed upon before work on the park could proceed. The resolution refers to a meeting between a group of 20 residents and Parks officials — Bob Redmond, a landscape architect, and Gail Wittwer Laird, supervisor of Parks’ Greenstreets program — and states, “The Department of Parks representatives promised at least two or three pieces of [Bolles’] sculpture would be returned and the traffic island would be designed so other pieces could be included.”

Jonathan Kuhn, Parks’ director of art & antiquities, came to last Thursday’s meeting to address the issue of the Bolles sculptures. He told The Villager he basically attended on his own, having found out about the meeting after seeing it listed in The Villager. However, he said he did mention it beforehand to Bill Castro, Manhattan borough Parks commissioner. Castro had been at the meeting to discuss the renovation of Washington Sq. Park but left right before the topic switched to the Bolles sculptures.

“The direct question is this — you promised us something and you didn’t come through with it. We have this on tape,” Kuhn was told by Larry White, a Soho photographer and one of the leading proponents for bringing back Bolles’ sculptures.

Kuhn noted he was not at the meetings where the agreements to return the sculptures were made.

“It’s right here in writing! God almighty!” exclaimed an exasperated White. “The word is broken.”

“No one is ever responsible,” said Don MacPherson, a C.B. 2 member who publishes “Soho Journal,” voicing frustration at Castro’s having left before they could raise the matter with him directly.

“We want it back,” said Aubrey Lees, the Parks Committee’s chairperson. “Can somebody get a truck and go get it?”

Kuhn said the answer is no and listed numerous reasons why, citing guidelines going back to 1860. First, he said, the city, in its donation guidelines, doesn’t accept ready-made art pieces for parks, and has turned away hundreds of art gifts over its history because they weren’t designed with the sites in mind. Also, for any permanent public artwork, the city assumes liability, he noted; if someone has an accident, such as a slip, involving the artwork, it could end up costing the city millions of dollars — “more than the [cost of the] Washington Sq. Park renovation,” Kuhn pointed out. In addition, the city’s Art Commission would not accept the piece because there was not a competitive process. Finally, he said, returning the sculptures could set a precedent that could be invoked at any of its 1,700 other parks, and that, “We can’t create policy park by park.”

“This is a different case,” stressed Tobi Bergman, a Parks Committee member. “Promises were made. Those promises should be kept. We were told that some of these pieces would be brought back. Parks never said, ‘They will be brought back if you get insurance.’ ”

Kuhn said they could bring some of the pieces back on a temporary basis; temporary installations can last a year, but are typically three to six months, he said. But the Soho artists and C.B. 2 committee weren’t interested in anything less than a permanent installation.

“Give us [dollar] figures. Tell us what we have to do,” said White. “Everything’s been so weird so far. We don’t know what to do.”

The Parks Committee approved a resolution recommending, as Lees phrased it, to “get the Bob Bolles sculptures returned — and get the Parks Department off their big old fat asses.”

However, White later said that in a conversation with Kuhn in the hallway after the meeting, things went much better and seemed more positive. Ken Reisdorff, owner of Broome St. Bar, told Kuhn that the sculptures were left to his family, meaning they could be legally donated to the site.

White said they’d ultimately like to have two or three of Bolles’ sculptures returned and also have a space for temporary installations.

White claims the sculptures meet Parks’ requirements in that they were site specific, all designed for and created on the site. But Kuhn called them “guerilla art in a quasi-public space.”

The Soho artists and activists feel Bolles’ works embodied the gritty spirit of early Soho, unlike what they describe as the bland park there now. Not only that, White said, but homeless people, screened from view by its foliage, now use the park as a bathroom.

In June 2001, Adrian Benepe, then-Manhattan borough Parks commissioner, now Parks commissioner, told The Villager that Parks was willing to bring back a few of Bolles’ better sculptures, though he thought the majority were “dangerous, dilapidated, rusting, falling-apart litter magnets.”

Asked if Kuhn was accurately reflecting the view of the Parks Department, Eric Adolfsen, a department spokesperson, confirmed Parks is currently working on bringing some of the sculptures back on a temporary basis. However, offering a slim ray of hope, he said some theoretically could be restored permanently, but that it would have to be done “by the book.” He referred the Bolles sculpture supporters to Parks’ Web site, www.nyc.gov/parks, specifically the section for permits and application guidelines for donating artwork. A formal presentation to the Art Commission would be required.

“Everything is possible,” said Adolfsen, “but you have to follow procedure.” Adolfsen said there are bound to be some in the community who would not want the art returned, and that it’s important to gauge the community’s sentiment.

A diagram above is a proposed idea for how Bob Bolles’ “Tree of Life” sculpture would be installed at Sunflower Park at Broome and Watts Sts. A solar-powered light would illuminate the artwork — an 8-ft.-tall metal pipe with cutout shapes — from inside at night.